Remarkable Drop in Colorado River Water Use a Sign of Climate Adaptation

An aerial view shows Lake Mead in Nevada on January 2, 2020. Daniel SLIM / AFP / Getty Images

By Brett Walton

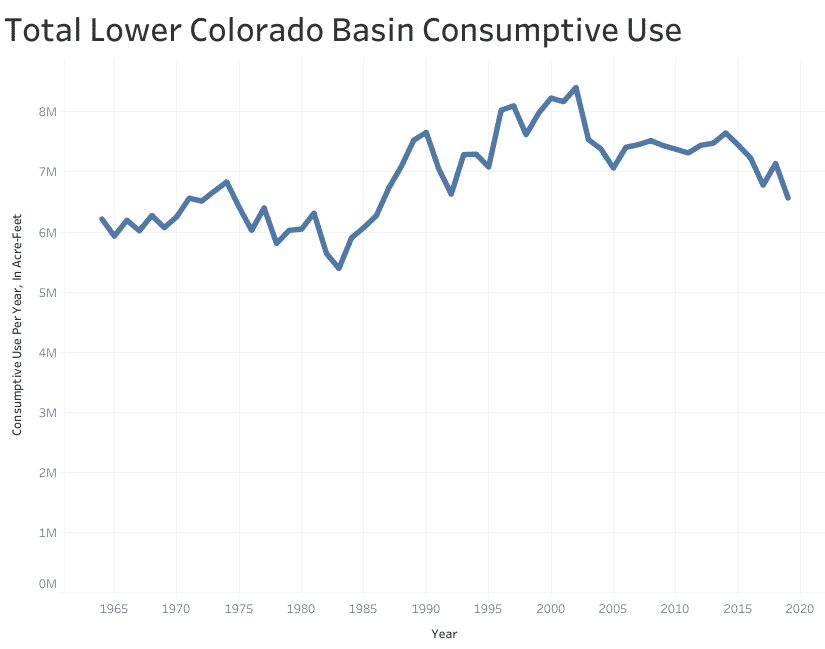

Use of Colorado River water in the three states of the river’s lower basin fell to a 33-year low in 2019, amid growing awareness of the precarity of the region’s water supply in a drying and warming climate.

Arizona, California, and Nevada combined to consume just over 6.5 million acre-feet last year, according to an annual audit from the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency that oversees the lower basin. That is about 1 million acre-feet less than the three states are entitled to use under a legal compact that divides the Colorado River’s waters.

The last time water consumption from the river was that low was in 1986, the year after an enormous canal in Arizona opened that allowed the state to lay claim to its full Colorado River entitlement.

States have grappled in the last two decades with declining water levels in the basin’s main reservoirs — Mead and Powell — while reckoning with clear scientific evidence that climate change is already constricting the iconic river and will do further damage as temperatures rise.

For water managers, the steady drop in water consumption in recent years is a signal that conservation efforts are working and that they are not helpless in the face of daunting environmental changes.

“It’s quite a turnaround from where we were a decade ago and really, I think, optimistic for dealing with chronic shortages on the river in the future, knowing that we can turn the dial back and reduce demand significantly, all three states combined,” said Bill Hasencamp, the manager of Colorado River resources for the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, a regional wholesaler and one of the river’s largest users.

Observers of the basin’s intricate politics are also impressed with the trend lines for a watershed that irrigates about 5 million acres of farmland and provides 40 million people in two countries and 29 tribal nations with a portion of their water.

“It is an incredibly important demonstration of the fact that we can use less water in this incredibly important water-use region,” John Fleck told Circle of Blue. Fleck is the director of the University of New Mexico water resources program.

Projections for 2020 indicate that conservation will continue, though not quite at last year’s pace. Halfway through the year, the Bureau of Reclamation forecasts water consumption to be roughly 6.8 million acre-feet. An acre-foot is the amount of water that will flood an acre of land to a depth of one foot, or 325,851 gallons.

“I have to give them credit,” Jennifer Gimbel, a senior water policy scholar at Colorado State University, told Circle of Blue about the lower basin states. “They’re working hard to get these numbers.”

Raising Lake Mead

Just five years ago, in 2015, the three states were making use of their entire 7.5-million-acre-foot allotment. By statute and tradition, the basin is divided into a lower basin, where use is higher, and an upper basin, which includes Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. The basins have different water allocation systems and rules governing its use.

In the lower basin, Arizona’s annual allocation is 2.8 million acre-feet, but last year it used just 2.5 million. Nevada used 233,000 of its 300,000 acre-feet. The big savings were in California, which used only 3.8 million of its 4.4 million acre-feet. California hasn’t used that little water from the Colorado since the 1950s, Fleck said.

The drop in California last year is due in large part to Metropolitan Water District, which consumed only 537,000 acre-feet. Five years ago, the district’s tally was around 1 million acre-feet per year. Urban conservation and development of local water sources have played a large role in the decline, but the district’s Colorado River water use is also influenced by snow levels in the Sierra Nevada mountains. When more water is available to be imported from the northern part of the state, as it was last year, the district leans less heavily on the Colorado River.

Reclamation’s annual audit measures the amount of water consumed by humans, plants, and animals in the lower basin. Consumptive use equals total withdrawals minus any water that is returned to the river system, from irrigation runoff or wastewater treatment plants.

As meticulous as it is, the audit neglects a significant piece of the basin’s water budget: evaporation from reservoirs and system losses, which is water consumed by riverside vegetation and absorbed by the ground. Together, these add up to about 1 million acre-feet per year, Jeremy Dodds, water accounting and verification group manager for Reclamation, told Circle of Blue.

This factor is part of the lower basin’s “structural deficit,” which means that total demand in the lower basin — use by Arizona, California, and Nevada, plus evaporation and required deliveries to Mexico — exceeds the amount of water that flows into Lake Mead, the lower basin’s supply source.

Gimbel, who was the principal deputy assistant secretary for water and science for the U.S. Department of Interior from 2014 to 2016, said that despite the conservation efforts reflected in the audit, the lower basin still has much work to do. “They’re closing the deficit, but they’re not there yet,” she said.

The goal of the lower basin’s conservation is to keep Lake Mead from a precipitous decline into “dead pool” territory, where the reservoir is too low to send water downstream. The dead-pool threshold is at elevation 895 feet. Not using 1 million acre-feet last year most certainly helped the reservoir. Dodds said that at the current elevation of 1,089 feet, each block of 85,000 acre-feet equals 1 foot of elevation. So last year’s conservation added 12 feet to Mead, compared to a scenario in which the three states use their full entitlement.

The conservation tool box that the states have employed has a range of instruments. Cities have provided incentives to remove grass lawns and replace inefficient toilets, showerheads, and washing machines. In Imperial Irrigation District, farmers have lined earthen canals with concrete to prevent seepage and they have agreed to fallow land to save water. Those measures, in both town and country, have helped to reduce demand. Supplies, on the other hand, have been bolstered by more investment in recycling and reuse, groundwater treatment, and desalination. As a whole, the seven states in the watershed came together in 2019 to modify rules for mandatory water-use restrictions that kick in as Lake Mead drops.

The decline in Colorado River water consumption mirrors regional and national trends. In Metropolitan Water District’s service area in Southern California, water use per person fell from about 181 gallons per person per day in the mid-1990s to 131 gallons in 2018, a drop of 27 percent. Colorado River consumption on the Colorado River Indian Tribes reservation, in Arizona, is down about 20 percent since 2016.

According to Tom Ley, a water consultant to the tribes, the decline is due to changes in farming practices and participation in a land fallowing program that will see 10,000 acres taken out of production in the next three years. The tribes’ decrease in consumptive water use “may look even more dramatic once the 2020 report comes out,” Ley told Circle of Blue.

All of these actions amount to a shift in the perception of what’s possible, Fleck said.

“It shows that the expectation that a growing population and a robust agricultural economy require more water is wrong,” explained Fleck, who is optimistic about the basin’s capacity to wield the tools of conservation effectively. Environmental doom is not the inevitable outcome, he says. “We’re seeing success in the transition away from the tragedy narrative,” he added.

Still, there are minefields to navigate. There are dozens of proposals in the upper basin states to withdraw more water from the river, which, if they were built, would further stress supplies. Some of the water conserved in Lake Mead is stored as a credit that participating agencies can theoretically draw upon in the future. How agencies handle those withdrawals, especially if large requests are made as lake levels plummet, is an uncertainty. On top of that, a warming climate will suck more moisture from the basin, even before rain and snow reach the river.

A hot, dry spring this year in the upper basin is evidence of what aridity can do. Snowpack in the basin’s headwaters was roughly average on April 1 and runoff into Lake Powell, a key water supply indicator, was expected to be 78 percent of normal. But then dry conditions arrived in April and May. Combined with dehydrated soils, which took their share of water, the runoff forecast by June 1 had diminished to just 57 percent of normal.

Those climate signals are the counterbalance to the conservation success so far. Water managers, now wary, know the risk.

“Just hopefully we don’t get a string of dry years coming back,” Hasencamp said.

This story originally appeared in Circle of Blue and is republished here as part of Covering Climate Now, a global journalism collaboration strengthening coverage of the climate story.

- 4 Ways to Beat the California Drought and Save the Colorado River ...

- Can Climate Action Plans Combat Megadrought and Save the ...

- Colorado River Has Lost 1.5 Billion Tons of Water to the Climate ...

- Local Conservation of a National Wild and Scenic River - EcoWatch

- Drought-Stricken Colorado River Basin Could See Additional 20% Drop in Water Flow by 2050 - EcoWatch

- California Faces ‘Critically Dry Year' - EcoWatch

- Dams and Climate Change Threaten American Rivers

- Alaska River Melt Betting Tradition Now Part of Climate Record

- Lake Powell Water Levels Fall to Lowest on Record

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe