Reducing Our Emissions Is the ‘Only Hope’ for Coral Reefs, Study Warns

Unless we act now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the world’s coral reefs will stop growing by the end of the century.

That’s the warning from a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Monday, which analyzed how the world’s reefs would fare under a low, medium and high emissions scenario.

“Our work highlights a grim picture for the future of coral reefs,” study lead author and Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington marine biologist Christopher Cornwall told ABC News.

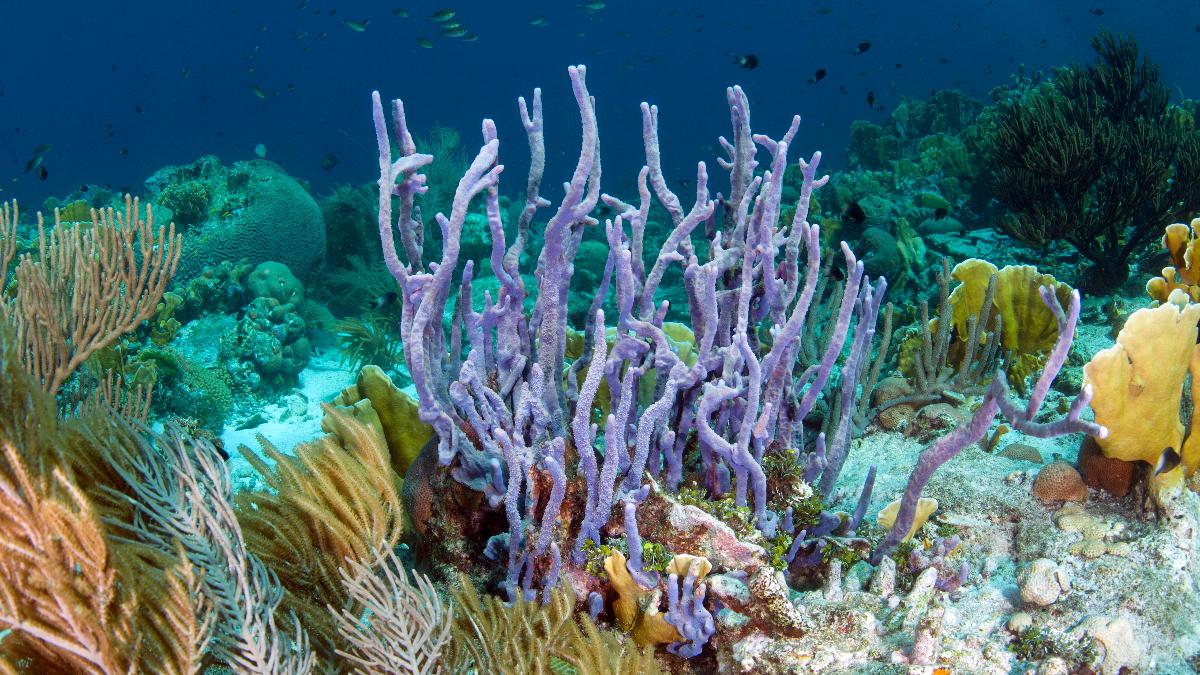

Scientists have long known that the climate crisis threatens coral reefs in two major ways. First, the increase of carbon dioxide in the ocean leads to a process called ocean acidification, which makes it harder for corals to form calcium carbonate skeletons, a process known as calcification. Secondly, warming ocean temperatures increase the risk of coral bleaching, when corals expel the algae that give them food and color. The warming can also interfere with the calcification process.

But there’s more. A certain type of algae known as calcifying red algae, or coralline algae, acts as adhesive binding reefs together and can even form its own reefs, Cornwall explained in a Victoria University of Wellington press release.

“While corals are highly susceptible to ocean warming, coralline algae are more vulnerable to ocean acidification. Coral reef growth is also dictated by the removal of this calcium carbonate through either bioerosion — living organisms eating the reef — or the dissolution of sediments that help fill in the cracks between larger pieces of calcium carbonate,” Cornwall explained. “Both processes are likely to accelerate under ocean acidification and warming. However, no one study had put these processes together quantitatively previously.”

Monday’s study sought to fill in this research gap by looking at calcification, bioerosion and sediment erosion rates for 233 areas on 183 reefs worldwide. Forty-nine percent of the reefs studied were in the Atlantic Ocean, 39 percent in the Indian Ocean and 11 percent in the Pacific Ocean. The researchers then used models to determine what would happen to the reefs in 2050 and 2100 based on low, medium or worst-case emissions scenarios.

The news is grim. By 2100, the rate of carbonate production on the reefs will decline by 76 percent under a low emissions scenario, 149 percent under a medium emissions scenario and 156 percent under a high emissions scenario, the study found.

While 63 percent of reefs would continue to grow under a low-emissions scenario by 2100, 94 percent of them would begin to decline as soon as 2050 in the worst-case scenario. Under both the medium and high emissions scenario, reef growth would not be able to keep pace with sea level rise by the end of the century.

This would be a devastating blow for the marine biodiversity and human livelihoods that reefs support, ABC News pointed out. Furthermore, the decline of reefs would deprive coastal areas from an important protection against rising sea levels and surges from more extreme storms.

“The only hope for coral reef ecosystems to remain as close as possible to what they are now is to quickly and drastically reduce our CO2 emissions,” Cornwall told ABC News. “If not, they will be dramatically altered and cease their ecological benefits as hotspots of biodiversity, sources of food and tourism, and their provision of shoreline protection.”

The research also looked at which reefs would be most vulnerable, and found that Atlantic Ocean reefs, which are already more damaged, would be worse off compared to Pacific Ocean reefs. The researchers also predicted that coral bleaching would be the lead cause of these declines.

“We are already observing global shifts in coral assemblages and severely reduced coral cover due to mass bleaching events. It is very unlikely corals will suddenly gain the heat tolerance required to resist these events as they become more frequent and intense,” Cornwall said in the press release.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe