Restoring Tropical Forests Isn’t Meaningful if Those Forests Only Stand for 10 or 20 Years

A regenerating stand of rainforest in northern Costa Rica. Matthew Fagan / CC BY-ND

By Matthew Fagan, Leighton Reid and Margaret Buck Holland

Tropical forests globally are being lost at a rate of 61,000 square miles a year. And despite conservation efforts, the global rate of loss is accelerating. In 2016 it reached a 15-year high, with 114,000 square miles cleared.

At the same time, many countries are pledging to restore large swaths of forests. The Bonn Challenge, a global initiative launched in 2011, calls for national commitments to restore 580,000 square miles of the world’s deforested and degraded land by 2020. In 2014 the New York Declaration on Forests increased this goal to 1.35 million square miles, an area about twice the size of Alaska, by 2030.

Ecological restoration is a process of helping damaged ecosystems recover. It produces many benefits for both wildlife and people — for example, better habitat, erosion control, cleaner drinking water and jobs.

That’s why the Bonn Challenge is so exciting for geographers and ecologists like us. It brings restoration into the center of global discussions about combating climate change, preventing species extinctions and improve farmers’ lives. It connects governments, organizations, companies and communities, and is catalyzing substantial investments in forest restoration.

However, a closer look shows that a struggle remains to fully realize the Bonn Challenge vision. Some reforestation efforts provide only limited benefits, and studies have shown that maintaining these forests for decades is critical to maximize the economic and ecological benefits of establishing them.

Putting Trees Back on the Land

So far, 48 nations and 10 states and companies have made Bonn Challenge commitments to restore 363,000 square miles by 2020 and another 294,000 square miles by 2030. The U.S. and a Pakistani province have already fulfilled their commitments, restoring a total of 67,000 square miles.

Restoring forests poses political and economic challenges for national governments. Letting forests grow back inevitably means pulling land out of farming. Natural forest regeneration mainly occurs where farmers have abandoned poor quality land, or where governments discourage poor farming practices — for example, near wetlands or on steep slopes. Opportunities for natural regeneration elsewhere are limited.

As a result, much forest landscape restoration under the Bonn Challenge focuses on improving existing landscapes using trees. Restoration activities may include creating timber or fruit plantations; agroforestry, or planting rows of trees in and around agricultural fields; and silviculture, or improving the condition of degraded forests.

One early success, the “Billion Tree Tsunami” in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, has exceeded its 350,000-hectare pledge through a combination of protecting forest regeneration and planting trees. Similarly, Rwanda has restored 700,000 of the 2 million hectares it pledged, primarily through agroforestry and reforesting erosion-prone areas, and created thousands of green jobs.

Green Deserts

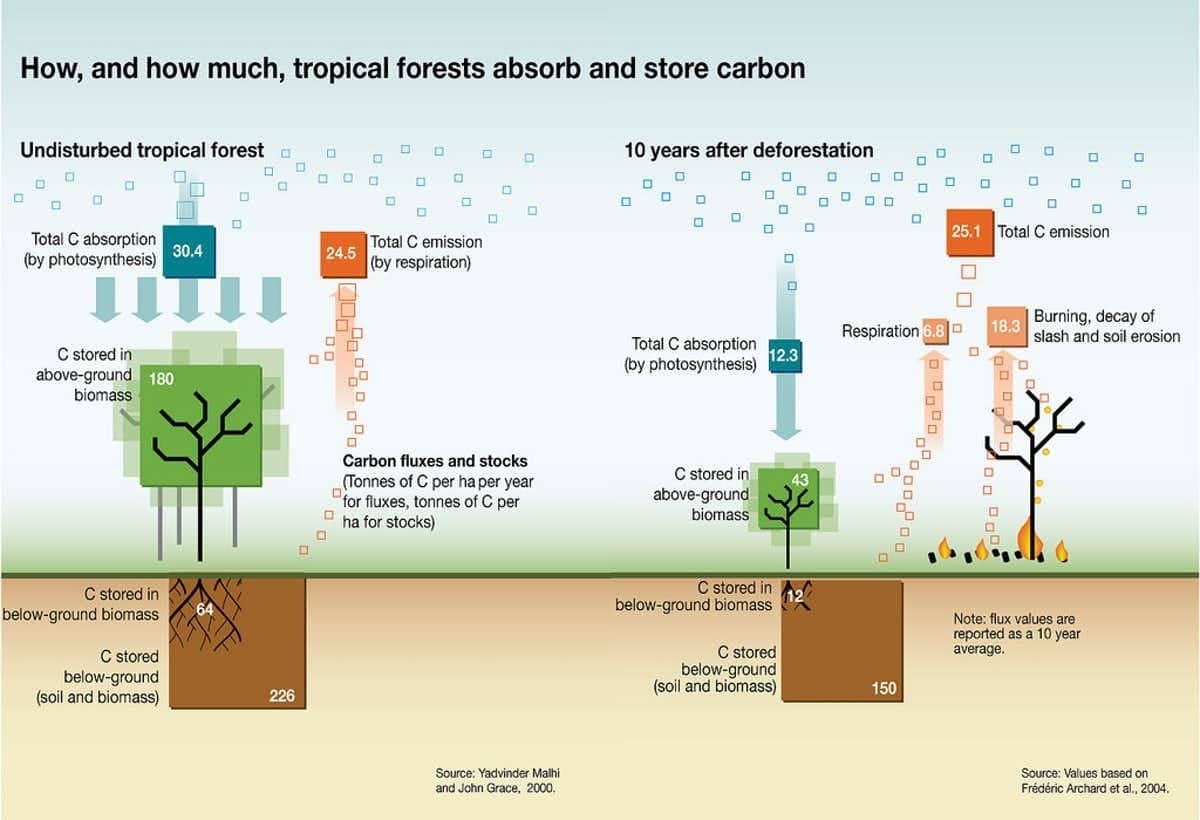

Logging and degradation of tropical forests is the main reason why forestry and land use account for 10–15 percent of the world’s total human-induced CO2 emissions.

However, these “restored forests” are often poor replacements for natural habitat. For animals dwelling in tropical forests, agroforestry and tree plantations can look more like green deserts than forests.

Many tropical forest wildlife species are only found in mature tropical forests and cannot survive in open agroforests, monoculture tree plantations or young natural regeneration. Truly restoring tropical forest habitat takes a diversity of forest species, and time.

Nonetheless, these working “forests” do have ecological value for some species, and can spare remaining natural forests from axes, fire and plows. In addition, scientists have estimated that restored forests could sequester up to 16 percent of the carbon needed to limit global warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, while generating some US billion in assets such as timber and erosion control.

Restored, but for How Long?

Benefits for wildlife and Earth’s climate from forest restoration accrue over decades. However, many forests are unlikely to remain protected for this long.

In a 2018 study we showed that forests that naturally regenerated in Costa Rica between 1947 and 2014 had only a 50 percent chance of enduring for 20 years. Most places where forests regrew were subsequently re-cleared for farming. Twenty years represents about a quarter of the time needed for forest carbon stocks to fully recover, and less than one-fifth of the time required for many forest-dwelling plants and animals to return.

Unfortunately, 20 years may be more than most new forests get. Studies in Brazil and Peru show that regenerating forests there are re-cleared even faster, often after just a few years.

This problem is not limited to natural forests. Agroforests worldwide are under pressure. For example, until recent decades, coffee and cocoa farmers in the tropics raised their crops in agroforests under a shady canopy of trees, which mimicked the way these plants grow in nature and maximized their health. Today, however, many of them grow their crops in the sun. This method can improve yield, but requires pesticides and fertilizer to compensate for added stress on the plants.

Solid Foundations for Recovery

If the Bonn Challenge is to achieve its goals, nations will have to find ways of converting short-term restoration pledges into long-term ecosystem recovery. This may require tightening the rules.

Some countries have pledged to protect unrealistically large areas. For example, Rwanda committed to restore 77 percent of its national territory, and Costa Rica and Nicaragua pledged to restore 20 percent of their territories apiece. Another flaw is that the Bonn Challenge does not prevent countries from deforesting some areas even as they are restoring others.

It will be impossible to track overall progress without an international commitment to monitor and sustain restoration successes. International organizations need to invest in satellite and local monitoring networks. We also believe they should consider how large international investments in sectors such as agriculture, mining and infrastructure drive forest loss and regrowth.

Countries like Indonesia that may be considering a Bonn Challenge pledge should be encouraged to focus on long-term impacts. Instead of restoring 10,000 square miles of one-year-old forest by 2020, why not restore 5,000 square miles of 100-year-old forest by 2120? Countries like Costa Rica that have already pledged can lock in those gains by protecting regrown forests.

The U.N. General Assembly recently approved a resolution designating 2021 to 2030 as the U.N. Decade of Ecosystem Restoration. We hope this step will help motivate nations to keep their promises and invest in restoring Earth’s deforested and degraded ecosystems.

Reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

- Abandoned Plantations Within Forests May Never Fully Recover ...

- European Moves to Restrict Palm Oil Have Enraged Malaysia and ...

- Keeping Trees in the Ground: An Effective Low-Tech Way to Slow Climate Change - EcoWatch

- Scientists Highlight Need to Restore Logged Rainforests in a Hotter and Drier Climate - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe