Environmental Concerns, Including Water Crises, Dominate Global Risks Report Rankings for First Time in History

A pillar measures the water level in a lake during a drought in Surin, Thailand. Sutthiwat Srikhrueadam / Moment / Getty Images

By Brett Walton

The world’s business elite, apprehensive about turbulent geopolitics after a year of international turmoil, nonetheless sees the biggest risks to society in the next decade coming from changes outside boardrooms and parliaments.

Degradation of the planet’s natural systems — its air, land, water and living creatures — is the most worrisome threat to social and political stability in the next 10 years, according to the World Economic Forum’s annual survey of leaders in business, academia, government and civil society.

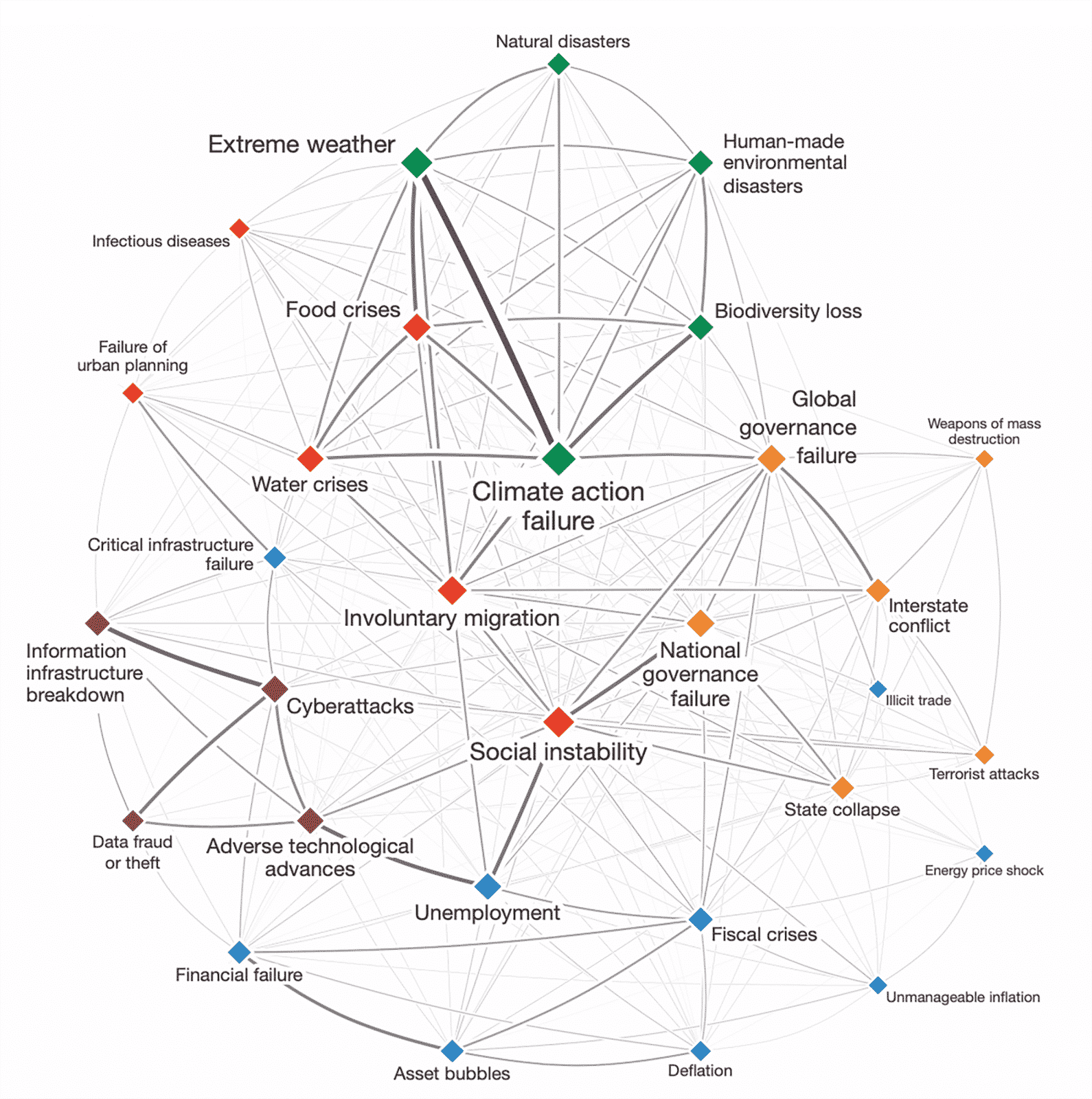

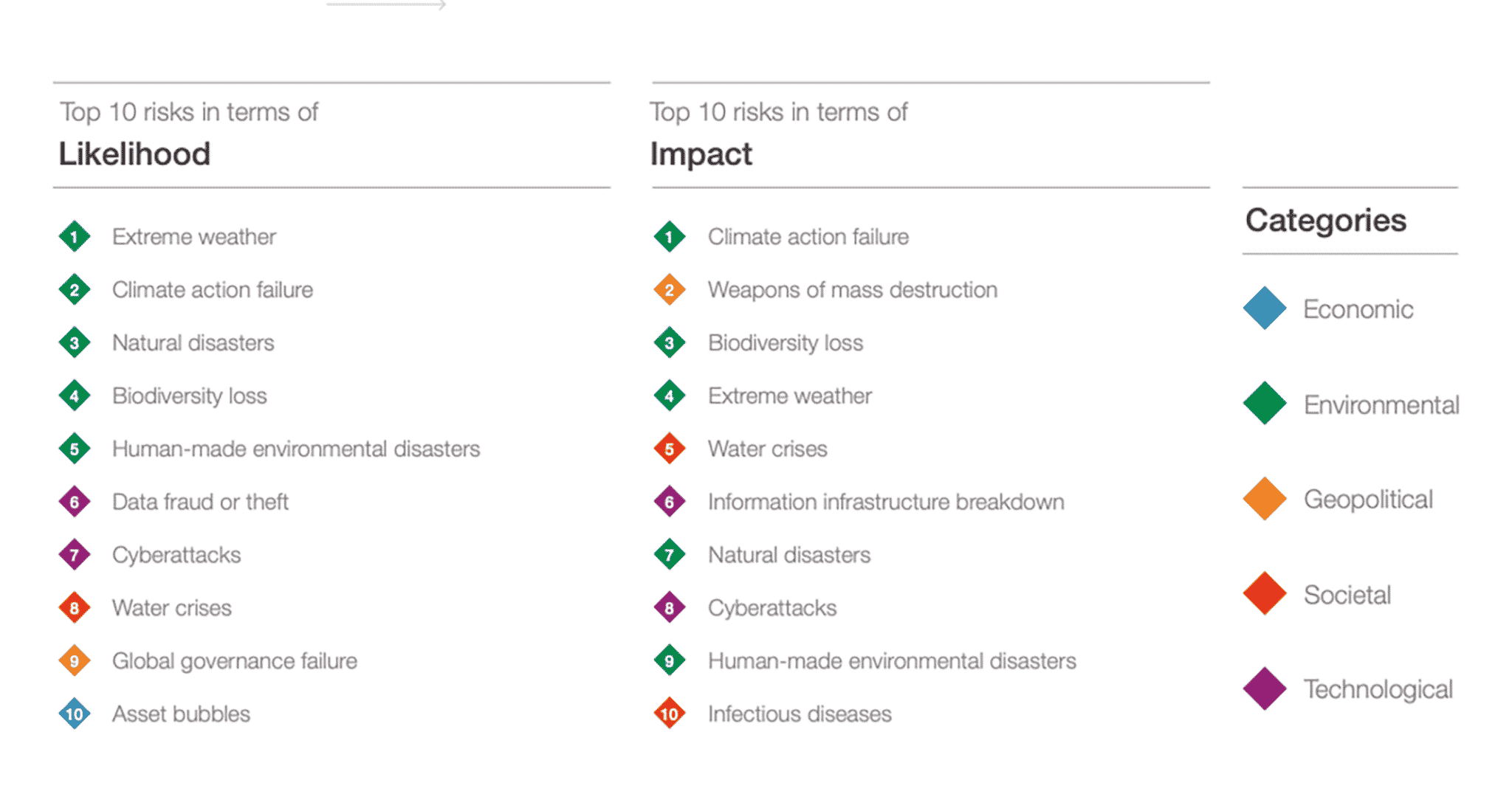

For the first time in the history of the Global Risks Report, respondents ranked environmental factors, including extreme weather and failure to respond to climate change, as the top five risks that are most likely to occur.

Image © World Economic Forum

On a second measurement — impact, or the damage that a risk can cause — four of the top five risks are environmental: climate change inaction, biodiversity loss, extreme weather and water crises. The other highly damaging risk: weapons of mass destruction.

The fifteenth edition of the report comes as local and national leaders face the intensifying consequences of a warming planet and man-made environmental harm. Some 400,000 displaced residents of Jakarta are reeling from the worst flooding in the Indonesian capital in decades, while Australia struggles to contain record-breaking bush fires that flared during the country’s hottest and driest year ever measured.

In the face of these disasters, millions of protestors took to the streets last year, calling for government and business leaders to take action before the window closes for avoiding the most severe climate impacts.

António Guterres, the secretary general of the United Nations, warned in December that that point is “in sight and hurtling toward us.”

Green Movement

Awareness of environmental factors has been building in the last decade. Early editions of the Global Risks Report, first published in 2006, were dominated by macroeconomic indicators such as oil prices, asset bubbles and government budgets. Attention to those issues was a consequence of the global financial crisis and Great Recession.

More nuanced thinking has emerged in recent years. Water crises, in acknowledgement of their far-reaching consequences, are now categorized as a societal risk. Threaded throughout the report are references to water’s connection to food production, human health, conflict, ecosystem function and extreme weather.

Extensive cutting of the Amazon rainforest, for instance, which accelerated in Brazil this year under President Jair Bolsonaro, will disrupt rainfall patterns and give rise to more frequent drought and wildfires, undermining water security in a region associated with abundant moisture, the report notes.

The boardrooms and government chambers that are registering concern for the consequences of climate change and environmental risk are the very locations in which actions to confront the hazards should be taken. Aquifers do not drain themselves and rising concentrations of heat-trapping greenhouse gases are a result of policy decisions made decades ago and fossil fuel subsidies that continue to this day.

“Achieving significant change in the near term will depend on greater commitment from major emitters,” the report notes, referring to measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Collaboration on all fronts is needed to counteract the hazards, says Borge Brende, president of the World Economic Forum.

And yet the politics of the moment — trade spats between China and the U.S., disdain by the Trump administration and other nationalist leaders for multilateral organizations like the United Nations, cleavage within the European Union — are straining traditional levers of collaboration, he argues.

“While these changes can create openings for new partnership structures, in the immediate term, they are putting stress on systems of coordination and challenging norms around shared responsibility,” Brende wrote in the report’s preface.

The report distills the responses of more than 1,000 people who completed the World Economic Forum’s annual risks survey. The typical respondent is a European businessman in his forties. More than two-thirds of people completing the survey were men. Forty-four percent of respondents call Europe home, and a quarter list their field of expertise as economics. The sectors that are most represented are business (38 percent), academia (21 percent) and government (15 percent).

Image © World Economic Forum

The survey asks respondents to rate 30 pre-selected global risks according to two metrics: their likelihood and their impact.

Generational differences are at play in the rankings — less in the type of risks that are of concern than the degree to which they are perceived as hazardous. Younger respondents were more likely to give greater weight to environmental risks. That cohort said that environmental risks such as extreme heat and illness linked to pollution would become more severe in the next year.

The Forum convenes its 50th anniversary meeting in Davos beginning Monday with an agenda that parallels many of the risk report findings and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Learn more about global risks and systemic connections through the World Economic Forum Strategic Intelligence Maps. Circle of Blue curates the water maps.

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2020 Priorities

Ecology: How to mobilize business to respond to the risks of climate change and ensure that measures to protect biodiversity reach forest floors and ocean beds.

Economy: How to remove the long-term debt burden and keep the economy working at a pace that allows higher inclusion.

Technology: How to create a global consensus on deployment of Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies and avoid a “technology war.”

Society: How to reskill and upskill a billion people in the next decade.

Geopolitics: How the ‘spirit of Davos’ can create bridges to resolve conflicts in global hotspots. Informal meetings to set kickstart conciliation.

Industry: How to help business create the models necessary to drive enterprise in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. How to navigate an enterprise in a world exposed to political tensions and driven by exponential technological change as well as increasing expectations from all stakeholders.

Reposted with permission from Circle of Blue.

- Even Davos Elite Warns Humanity Is 'Sleepwalking Into Catastrophe ...

- Climate Change Named Biggest Global Threat in New WEF Risks ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe