In a Warming World, Carolina CAFOs Are a Disaster for Farmers, Animals and Public Health

By Karen Perry Stillerman

In the aftermath of Hurricane Florence, I’ve joined millions who’ve watched with horror as the Carolinas have been inundated with floodwaters and worried about the various hazards those waters can contain. We’ve seen heavy metal-laden coal ash spills, a nuclear plant go on alert (thankfully without incident), and sewage treatment plants get swamped. But the biggest and most widely reported hazard associated with Florence appears to be the hog waste that is spilling from many of the state’s thousands of CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations), and which threatens lasting havoc on public health and the local economy.

And while the state’s pork industry was already under fire for its day-to-day impacts on the health and quality of life of nearby residents, Florence has laid bare the lie that millions of animals and their copious waste can be safely concentrated in flood-prone coastal areas like southeastern North Carolina.

CAFO “Lagoons” are Releasing a Toxic Soup

The state is home to 9.7 million pigs that produce 10 billion gallons of manure annually. As rivers crested on Wednesday, state officials believed that at least 110 hog manure lagoons—open, earthen pools where pig waste is liquified and broken down by anaerobic bacteria (causing their bubblegum-pink color) before being sprayed on fields—had been breached or inundated by flood waters across the state:

The tally by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality is rising rapidly (it was just 34 on Monday). Perhaps not surprisingly, the state’s pork industry lobby group is reporting much smaller numbers: by Wednesday afternoon, the North Carolina Pork Council’s website listed only 43 lagoons affected by the storm and flood.

In any case, the true extent of the spills may not be known for many days, as extensive road closures in the state continue to make travel and assessment difficult or impossible.

The Scale of North Carolina’s CAFO Industry is Shocking

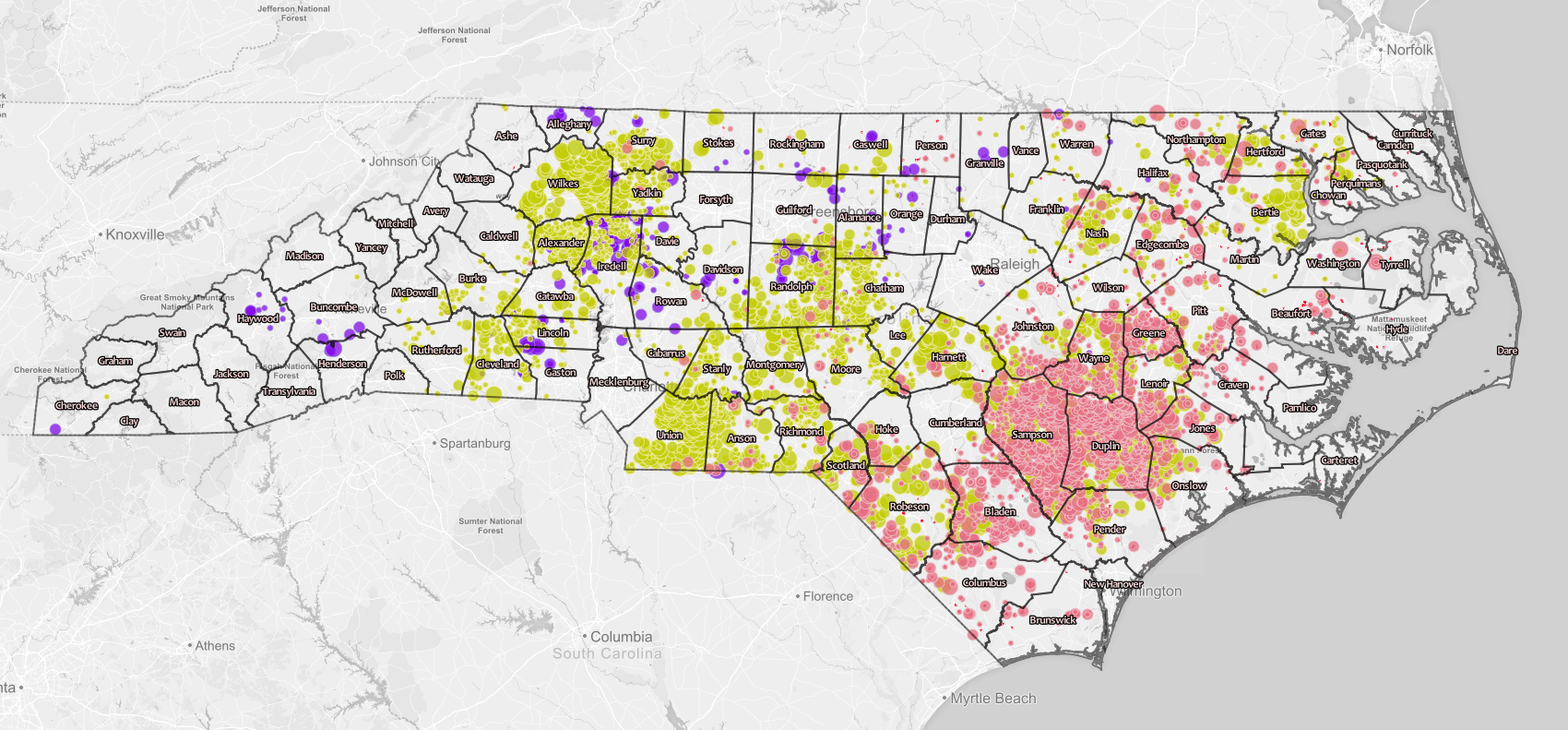

In 2016, the Waterkeeper Alliance and the Environmental Working Group used federal and state geographical data and analyzed high-resolution aerial photography to create a series of interactive maps showing the locations and scale of CAFOs concentration in the state. The map below shows the location of hog CAFOs (pink dots), poultry CAFOs (yellow dots) and cattle feedlots (purple dots) throughout the state.

Waterkeeper Alliance and the Environmental Working Group used public data to create maps of CAFO locations in North Carolina in 2016.

Note the two counties in the southeastern part of the state, Duplin and Sampson, where the most hog CAFOs are concentrated—nearly as pink as a hog lagoon, these counties are Ground Zero for the state’s pork industry. In Duplin County alone, where hogs outnumber humans 40-to-1, the Waterkeeper/EWG data show there were, as of 2016, more than 2.3 million head of swine producing 2 billion gallons of liquid waste per year, stored in 865 waste lagoons. (Duplin County was also home to 1,049 poultry houses containing some 16 million birds that year.)

The State’s CAFOs Harm Communities of Color Most

“Lagoon” is a curious euphemism for a cesspool. Even without hurricanes, these gruesome ponds pose a hazard to nearby communities. In addition to the obvious problem of odor, they emit a variety of gases—ammonia and methane, both of which can irritate eyes and respiratory systems, and hydrogen sulfide, which is an irritant at very low exposure levels but can be extremely toxic at higher exposures.

These everyday health hazards hurt North Carolinians of color most of all. To pick on Duplin County again, U.S. Census figures show that one-quarter of its residents are black and 22 percent are Hispanic or Latino. And a 2014 study from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that, compared to white people, black people are 54 percent more likely to reside near these hog operations, Hispanics are 39 percent more likely, and Native Americans are more than twice as likely.

What does all that mean for health and environmental justice? Residents near the state’s hog CAFOs have complained for years of sickening odors, headaches, respiratory distress and other illnesses, and have filed (and begun winning) a series of class-action lawsuits against the companies responsible for them.

Just this month, researchers at Duke University published new findings on health outcomes in communities close to hog CAFOs in the state. They found that, compared with a control group, such residents have higher rates of infant death, death from anemia, and death from all causes, along with higher rates of kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia, emergency room visits and hospital admissions for low-birthweight infants. (Read the full study or this review.)

CAFO damage from Florence was predictable … and will get worse

Releases of bacteria-laden manure sludge from CAFO lagoons in flooding like we’re seeing this week compound the day-to-day problem, and they’re inevitable in a hurricane- and flood-prone state like North Carolina. Between 1851 and 2017, 372 hurricanes have affected the state, with 83 making direct landfall in North Carolina. Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016 wreaked havoc similar to what we’re seeing this week.

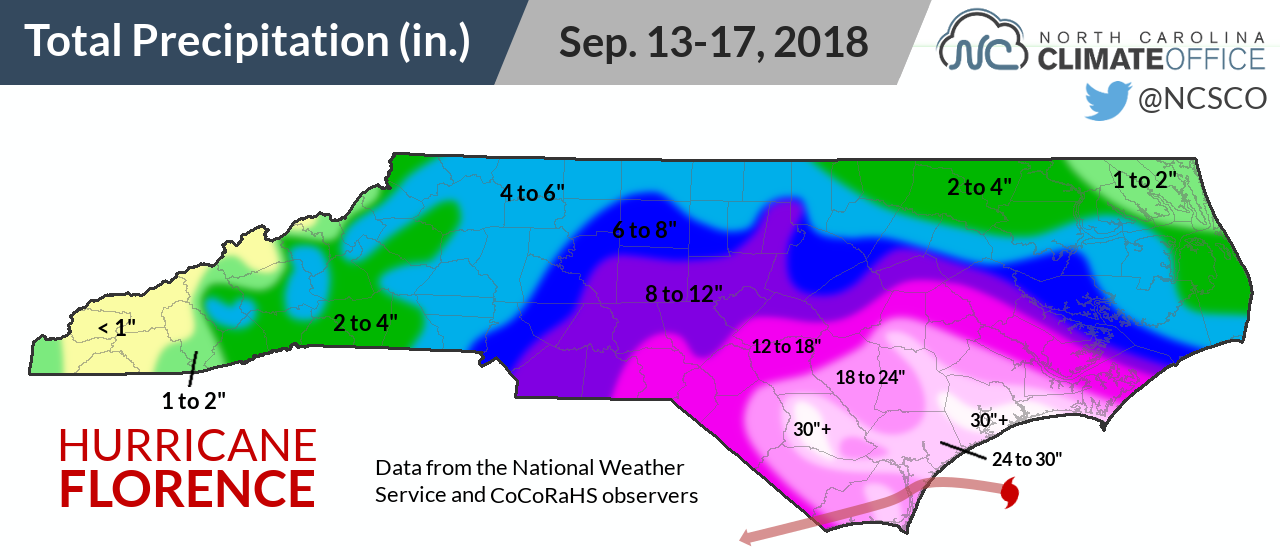

As you can see on the map below, Florence dumped between 18 and 30+ inches on every part of Duplin County.

It’s not surprising that flooding from such an event would be severe. And while the North Carolina Pork Council called Florence “a once-in-lifetime storm,” anyone who’s paying attention knows it’s just a matter of time before the next one.

Millions of Animals are Likely Drowned, Starved or Asphyxiated

In addition to the effects on communities near North Carolina’s CAFOs, it’s clear that Hurricane Florence has caused tremendous suffering and death to animals housed in those facilities. Earlier this week, poultry company Sanderson Farms reported at least 1.7 million chickens dead, drowned by floodwaters that swamped their warehouse-like “houses.” Some 6 million more of the company’s chickens cannot yet be accounted for. Overall, the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services on Tuesday put the death toll at 3.4 million chickens and turkeys and 5,500 hogs, but those numbers may very well rise.

A major reason we don’t yet know the full extent of animal deaths in North Carolina’s CAFOs is that road closures due to flooding has cut off many of the facilities, preventing feed deliveries and inspections. Many animals likely also died in areas that experienced power failures due to the storm. According to this poultry industry document, a power outage that interrupts the ventilation system in a totally enclosed poultry CAFO can kill large numbers of birds by asphyxiation “within minutes.”

North Carolina Farmers Face Staggering Financial Losses and Likely Bankruptcies

And what about the farmers? Many of the nation’s hog and poultry producers are in already in a predicament. Corporate concentration has squeezed out many independent farmers, meaning more operate as contractors to food industry giants like Smithfield and Tyson. In the U.S. pork industry, contract growers accounted for 44 percent of all hogs and pigs sold in 2012. The farmers have little power in those contracts, and an early action of the Trump administration’s USDA served to remove newly-gained protections against exploitation by those companies. The administration’s trade war isn’t helping either.

As one expert in North Carolina put it as Hurricane Florence approached:

A farmer (who operates a CAFO) has very little flexibility. They take out very large loans, north of a million dollars, on a facility that is specifically designed by the industry, as well as how the facility will be managed. Remember that 97% of chickens and more than 50% of hogs are owned by the industry. These farmers never even own the animals. But if the animal dies, and how to handle the waste, that’s on the farmer. That’s their responsibility.

I know many individual farmers who do the best they can, who work as hard as they can, who treat their animals with respect. But there’s only so much they control. They can’t control the weather. They can’t control the hurricane. These farmers are part of an industry that says, for the sake of efficiency, you have to put as many animals as possible into these facilities.

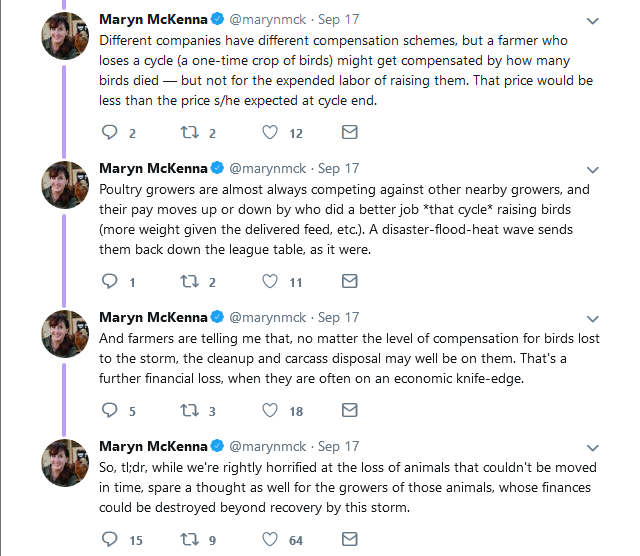

Post-Florence, these contract farmers are likely to receive inadequate compensation for the losses of animals in their care. A series of tweets this week by journalist Maryn McKenna, who has studied the poultry industry, illuminates the issues:

So, as the waters recede, many hog and poultry farmers are about to find themselves responsible for a ghastly cleanup job. Imagine returning home to find thousands of bloated animal corpses rotting in the September sun. They they were your livelihood, and now they’re not only lost, but an actual liability you must pay to have hauled away.

Public Policies Should Encourage Sustainable Livestock Production, not CAFOs

And so it goes for farmers in today’s vertically-integrated, corporate-dominated, CAFO model. But it doesn’t have to be this way. Public policies can give more power to livestock farmers in the marketplace, protect animals and nearby communities from hazards associated with CAFOs, and facilitate a shift to more environmentally and economically sustainable livestock production practices.

If Hurricane Florence teaches us anything, it’s that flood-prone coastal states like North Carolina are no place for CAFOs. At a minimum, the state must tighten regulations on these facilities to protect public health and safety. A 2016 WaterKeeper Alliance analysis found that just a dozen of North Carolina’s 2,246 hog CAFOs had been required to obtain permits under the Clean Water Act, with the rest operating under lax state regulation. The state and federal government should also more aggressively seek to close down hog lagoons and help farmers transition to more sustainable livestock practices or even switch from hogs to crops. A buyout program already exists but needs much more funding.

In the meantime, the federal farm bill now being negotiated by Congress also has a role to play. At least one farm bill program, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, has been used in ways that underwrite CAFOs. In a 2017 analysis of FY16 EQIP spending, the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition noted that 11 percent ($113 million) of EQIP funds were allocated toward CAFO operations, funding improvements to waste storage facilities and subsidizing manure transfer costs. And the House version of the 2018 farm bill could potentially increase support for CAFOs by eliminating the Conservation Stewardship Program—which incentivizes more sustainable livestock practices and offers a 4-to-1 return on taxpayer investment overall—and shifting much of its funding to EQIP.

The post-Florence mess in North Carolina illustrates precisely why that’s a bad idea. Particularly in a warmer and wetter world, public policies and taxpayer investments should seek to reduce reliance on CAFOs, not prop them up.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe