Saint Mary Lake and Wild Goose Island, Glacier National Park, a UNESCO designated World Heritage Site. Ken Thomas / Wikimedia Commons

By Giovanni Ortolani

The U.S. is quitting UNESCO, the United Nations organization that coordinates international efforts to foster peace and sustainable development, and to eradicate poverty. The Trump administration made the announcement on Oct. 12. The withdrawal takes effect Dec. 31, 2018, and the U.S. will remain a full member until then.

“This decision was not taken lightly, and reflects U.S. concerns with mounting arrears at UNESCO, the need for fundamental reform in the organization, and continuing anti-Israel bias at UNESCO,” said Heather Nauert, a U.S. State Department spokesperson in a press statement.

The U.S. does, however, say it will seek to stay engaged with the organization as a non-member observer state in order to “contribute U.S. views, perspectives and expertise on some of the important issues undertaken by the organization,” including the protection of World Heritage Sites and the promotion of scientific collaboration.

Trump isn’t the first U.S. president to have antagonism toward the organization. Although America has played an important role in UNESCO since its creation after World War II, Trump’s predecessors have been quarreling with it since the 1970s.

“We were in arrears to the tune of $550 million or so, and so the question is, do we want to pay that money?” Nauert said at a news briefing, making clear that “with this anti-Israel bias that’s long documented on the part of UNESCO, that [U.S. relationship] needs to come to an end.”

But what does the Trump administration’s withdrawal mean for UNESCO environmental programs worldwide? And will the loss of U.S. money matter?

A moment of great hope when UNESCO declared 2015 the International Year of Light at the Paris Climate Summit. Athalfred DKL on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

UNESCO environmental and science programs

The UN Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organization was founded in 1945, and is a catalyst for far-reaching and important environmental and sustainable development initiatives. Today it’s the only UN organization with a clear science mandate, and it works on a broad scope of environmental issues, directing projects from a scientific, cultural, social and educational perspective.

UNESCO’s Natural Sciences Sector, headquartered in Paris, has a staff of 120, with 54 field offices around the world, and it hosts major international programs in the freshwater, ecological, earth and basic sciences.

Its activities deal with the ecological sciences (Man and the Biosphere Programme and World Network of Biosphere Reserves), water security (International Hydrological Programme and World Water Assessment Programme), and earth sciences (International Geoparks and Geoscience Programme, and disaster risk reduction).

Man and the Biosphere (MAB) is one of UNESCO’s best-known programs, with its World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR). Launched in 1971, MAB seeks to improve relationships between people and their environments by protecting areas nominated by national governments. MAB reserves remain under sovereign jurisdiction of the states where they’re located, but enjoy international recognition.

“Biosphere Reserves are learning places for sustainable development whose aim is to reconcile biodiversity conservation and the sustainable use of natural resources,” read a recent UNESCO press statement when it added 23 new sites to WNBR. The Trump administration is voluntarily withdrawing 17 sites from the program. However, withdrawal isn’t unusual and other countries including the UK, Austria, Australia, Norway, Bulgaria and Sweden have withdrawn MAB sites in the past. Among those being withdrawn by the U.S. currently is the Hubbard Brook, New Hampshire, U.S. Forest Service reserve, where groundbreaking forest ecosystem and climate research has been ongoing for decades.

Today WNBR encompasses 669 sites in 120 countries, including 16 transboundary biosphere reserves, covering over 680 million hectares (2.6 million square miles) of inland, coastal and marine areas, and representing all major ecosystem types and diverse development contexts. These areas are home to approximately 207 million people ranging from rural and indigenous communities to urban dwellers.

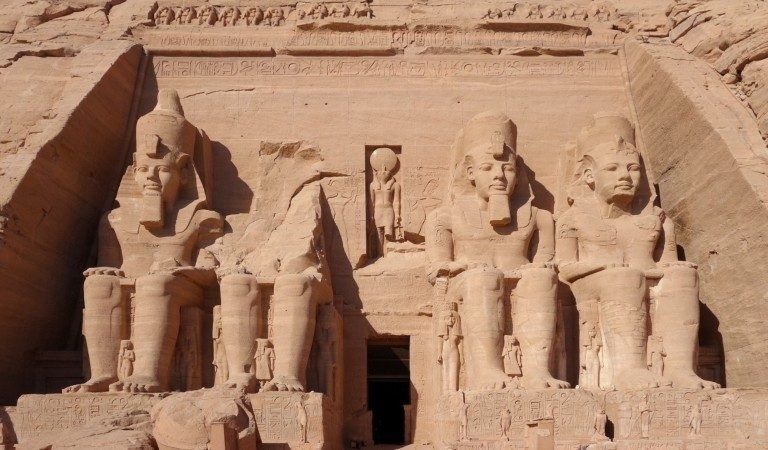

UNESCO launched an international campaign to save the Abu Simbel Temple monuments in Egypt in the 1960s from being flooded by Lake Nasser. The project drew unprecedented international attention and praise for UNESCO’s protection of the world’s cultural heritage.VisualHunt.com

Water programs

The International Hydrological Programme (IHP) does scientific, educational and capacity building around water issues. IHP promotes an interdisciplinary, integrated approach to watershed and aquifer management, and does international research in the hydrological and freshwater sciences.

It also assists UNESCO member states in water security efforts, addressing challenges such as water-related disasters and hydrological changes, groundwater, water scarcity and quality, and ecohydrology—the study of the interrelationships between hydrological and biological processes required to enhance water security and lessen ecological threats.

The World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP) produces an annual World Water Development Report, a coordinated effort achieved across the UN system and provides a clear picture of the state of the world’s freshwater resources to member nations.

Pamukkale, Turkey, a UNESCO World Heritage Site famous for its hot springs and enormous white terraces of travertine, a carbonate mineral sediment left by flowing water. Visualhunt.com

Earth science programs

UNESCO’s programs in earth sciences support research that informs current challenges such as evidence of global change from the geological record, geoscience of the water cycle, or environmental geodynamics.

The Environmental and Health Impacts of Mining Activities in Sub-Saharan African Countries is a good example of how valuable this knowledge can be. This program in fact does not only aim to understand how the mining activities (and particularly abandoned mines) negatively affect the soils, animals, plants and fungi, surface and groundwater, and the health of neighboring communities. It also experiments with the most appropriate mining rehabilitation technologies, and provides science-based data to governments and local authorities on both land-use planning and technologies to mitigate environmental disaster in contaminated regions.

UNESCO Global Geoparks are areas where landscapes and sites of international geological significance are managed via a holistic approach to protection, education and sustainable development. As of today, there are 127 Geoparks in 35 countries, ranging from Vietnam to Brazil.

The organization also supports the meaningful inclusion of local and indigenous knowledge in biodiversity conservation and management, especially climate change assessment and adaptation via the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) has its own membership and a separate chapter in the organization’s program and budget. IOC is the only body devoted to marine science within the UN system, and the U.S. has been involved in it since its establishment in 1960, mainly through the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The future of that relationship is uncertain now.

The U.S. has played an important role in many IOC programs critical to ocean health and the wellbeing of coastal communities. For instance, the Global Tsunami Warning System that covers four major ocean basins (Pacific, Indian, Caribbean, and Mediterranean/North Eastern Atlantic), or the Harmful Algal Blooms program, which develops research and provides guidance to address “red tides” now threatening a wide range of coastal economic sectors (fishing, tourism, navigation, aquaculture).

NOAA and NASA are also pivotal to IOC’s Global Ocean Observing System: the U.S. has in particular been leading the deployment of Argo floats around the globe to enhance measurements of ocean temperature, salinity and currents. The U.S. is a key contributor to observations of sea-level rise, ocean water acidification and a number of other variables to enhance understanding and predict trends and impacts of climate change, El Niño, and other ocean-related phenomena. It is uncertain precisely how that relationship will function in future.

The Okavango Delta, Botswana, World Heritage Site is home to some of the world’s most endangered species of large mammal, including the elephant, cheetah, white rhinoceros, black rhinoceros, African wild dog and lion. Pete Hancock / UNESCO

Who benefits, who gets hurt?

“While the U.S. will remain engaged in many of these programs, the absence of U.S. funding makes it increasingly difficult to meet the challenges that are so vital to the lives and livelihoods of millions of Americans,” George Papagiannis, UNESCO’s Media Services Chief told Mongabay in an email, pointing out that “an ounce of investment is worth a pound of cure.”

Papagiannis stressed a simple fact: UNESCO programs, and the critical environmental problems they seek to solve, do not only result in benefits to countries far from the White House, but instead greatly benefit the U.S. and millions of American citizens.

“A submerged lower Manhattan during hurricane Sandy, or the blooming red tides that affect the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico, are reminders that the U.S. is no safer than most countries from ocean related hazards,” he said, adding that no single country, regardless of national capacity, can tackle these cross-border issues on its own.

“Whether it is about safeguarding coastal economies and jobs, ensuring people’s safety and public health, or protecting infrastructures, U.S. investments on IOC activities in ocean science and services create benefits to its citizens that far outweigh the costs,” he said.

Ancient Maya City and Protected Tropical Forests of Calakmul, Campeche, Mexico, a World Heritage Site. Archivo / RBC-CONANP

The IOC also provides an intergovernmental coordination platform for effective collective action, from which all Member States benefit. Of course, that cooperative approach doesn’t fit in well with President Trump’s “Make America Great Again,” go-it-alone approach.

As an example, the UN General Assembly is discussing a proposal by IOC to declare 2021-2030 as the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, under the UN’s global coordination. “The U.S. government and its scientific institutions stand to benefit enormously from participating in this collective framework for coordinating and consolidating the observations and research needed to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 14 on the ocean,” Papagiannis said, pointing out that “it will be the time to bolster innovative technologies and scientific knowledge to bring tangible wellbeing and economic benefits to U.S. citizens.”

It is also worth noting that much of UNESCO’s work addresses the root causes of mass human migration, promoting sustainable and equitable management of national natural resources, and providing or fostering livelihoods, notably in Biosphere Reserves.

Loss of U.S. funding started in 2011

Strange as it may sound, there will be no immediate financial consequences related to the U.S. withdrawal from UNESCO because the U.S. has not paid its dues since 2011 during the Obama administration when the Palestinian Authority was accepted into the UN agency as a full member. The funding cut then was across the board, resulting in a 22 percent hit to the UNESCO budget more than $80 million per year, according to this Foreign Policy report. Since then, all parts of the organization have adapted to new financial realities.

Clearly there have been consequences since 2011, and UNESCO has never fully recovered from the loss. The approved budget allocated to Science and the International Oceanographic Commission (IOC) for the 2010-2011 biennium was $59,074,000, while the approved expenditure plan for the current biennium (2016-2017) for Science and the IOC falls below that amount, coming in at $48,308,400.

The Isla Genovesa Booby Sanctuary, Tower Island, Galapagos World Heritage Site. David Broad / Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

As a result, the number of permanent science positions has decreased, while less funding has meant a sharp refocusing of the organization’s work. For example, Papagiannis said, UNESCO’s Basic Sciences efforts were severely impacted, and the organization is no longer directly involved in earth observation and remote sensing projects, with few exceptions. That’s a serious problem when one considers the rapid natural changes underway due to climate change. Furthermore, UNESCO no longer spends regular budget on renewable energy activities, and its engineering activities have been strongly curtailed.

In addition to its assessed contribution, the U.S. used to fund projects directly, a procedure known as “extra-budgetary funding.” This means that UNESCO received money from the U.S. State Department, USAID, Department of Defense and National Science Foundation for seismicity and earthquake engineering in the Mediterranean and in Northeast Asia, and cooperation with the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering. The last of the funds allocated as extra-budgetary were received in November 2011 and spent by 2014.

One discontinued project was the Open Initiative with the Space Agencies, which included NASA, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the U.S. Geological Survey. This initiative used space imaging to monitor and protect World Heritage sites, and was discontinued five years ago. Interestingly that task has now been taken on by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which seems to value science more than the current U.S administration.

Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Philippines, World Heritage Site. Roy F. Ponce / UNESCO

Who is the real loser?

According to Papagiannis, “the withdrawal of the U.S. will have an impact on the United States’ level of engagement in global science programs, and in the leadership of these program.”

But in statements emailed to Mongabay, a State Department official wrote, “U.S. withdrawal from UNESCO does not alter U.S. policy of supporting international cooperation in educational, scientific, cultural, communication and information activities where there are benefits to the United States. By pursuing non-member observer status, it is our intention to remain participants in UNESCO programs, such as IOC, where non-member observers may have a role.”

However, the statement continues, the dimensions of this observer participation remain to be defined. Currently the U.S. is focused on preparing its request for non-member observer status so that it may remain engaged on “non-politicized issues” undertaken by UNESCO.

“When it is in the U.S. interest,” stressed the official, “the United States will continue to participate in UNESCO and UNESCO-related activities that do not require membership in the Organization.”

Melinda Kimble, Senior Fellow at the United Nations Foundation, asserts that UNESCO’s scientific and environmental programs provide core elements that support national and regional planning for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”—a commitment to eradicate poverty and achieve sustainable development by 2030 worldwide adopted in 2015 by heads of state and government at a special UN summit.

“Clearly, an active and fully contributing U.S. could make a difference in sustaining UNESCO’s leadership in education, science and culture,” she told Mongabay.

This is not the first time the U.S. has left UNESCO. The Reagan Administration withdrew in 1984 because of concerns over many issues, ranging from Soviet Union disarmament proposals to the organization’s request for a budget increase. When the U.S. pulled out then, it was not in arrears and continued supporting UNESCO programs with voluntary financial contributions.

Karibik, St. Kitts, Brimstone Hill Fortress National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. giggel / Creative Commons Attribution 3.0

Then after an almost twenty-year absence, the U.S. rejoined the organization in 2003. President George W. Bush announced the move “as a symbol of our commitment to human dignity … This organization has been reformed and America will participate fully in its mission to advance human rights and tolerance and learning.”

As for Trump’s planned withdrawal, Kimble agreed that “Clearly, an active and fully contributing USA could make a difference in sustaining UNESCO’s leadership in education, science and culture.” She noted that while the current pullout underscores U.S. skepticism about the UN system and multilateral action in many spheres, the real damage was done not by Trump but starting in 2011 with the U.S. failure to contribute financially.

“[T]he failure to pay dues has significantly undermined the capacity of the organization to deliver on its ambitious programs,” Kimble concluded.

Under the terms of the original 1945 treaty establishing the United Nations and UNESCO, the U.S. as a Member State remains obligated to paying its arrears. “But this is not just about the money,” said Papagiannis. “This [withdrawal represents] a loss for multilateralism and a blow to universality, which are critical factors to addressing the issues that affect people everywhere in every country.”

In October, after receiving official notification by U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova expressed profound regret at the decision.

“In 2011, when payment of membership contributions was suspended at the 36th session of the UNESCO General Conference, I said I was convinced UNESCO had never mattered as much for the United States, or the United States for UNESCO. This is all the more true today, when the rise of violent extremism and terrorism calls for new long-term responses for peace and security, to counter racism and anti-semitism, to fight ignorance and discrimination,” she said in a press statement.

“I believe UNESCO’s action to enhance scientific cooperation, for ocean sustainability, is shared by the American people,” she added.

As the world rushes headlong into a century of scientific uncertainty—where the climate, oceans, freshwater, ecosystems and human communities grow increasingly unstable and at risk—it remains to be seen just how long America will want to go it alone, rather than joining with the rest of the world to share in the costs and benefits of international science in order to serve the common good.

Sequoia-Kings Canyon Biosphere Reserve is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve located in the southern Sierra Nevada of California. Photo by thor_mark on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Reposted with permission from our media associate Mongabay.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe