Why Scientists Are Searching for Life in ‘Alien Oceans’ on Distant Moons

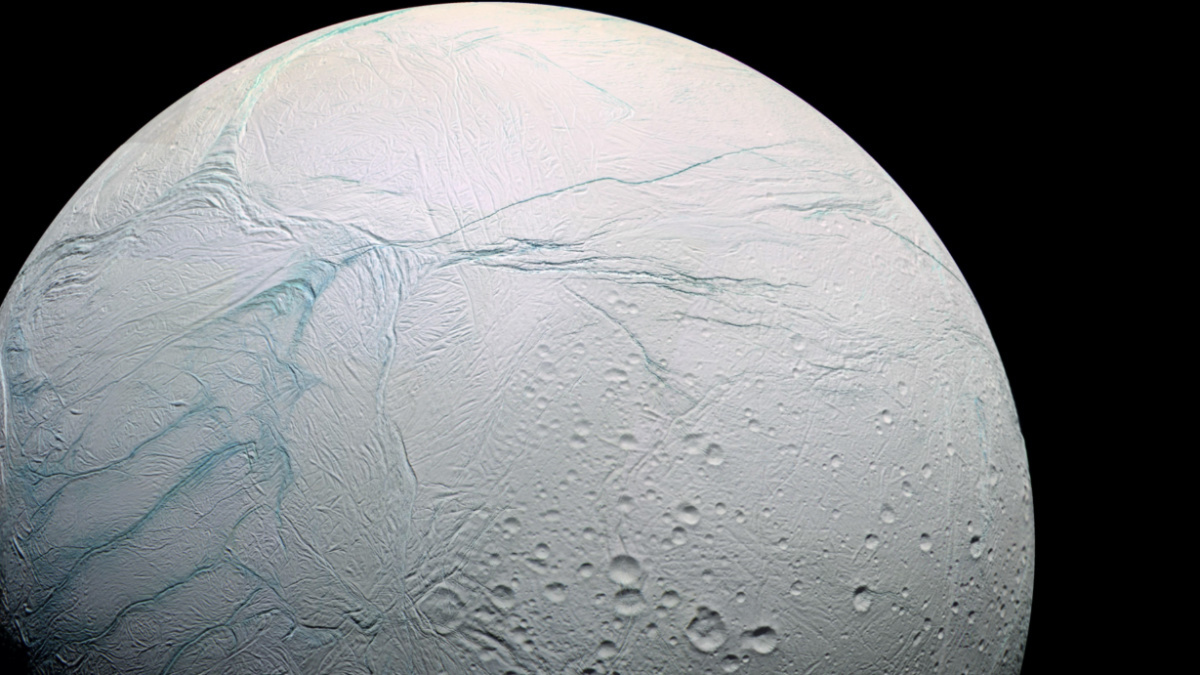

Saturn's moon, Enceladus, is one of three moons that appear to contain subsurface oceans underneath an icy shell. Marc Van Norden / NASA / Flickr / CC by 2.0

By Zulfikar Abbany

“We don’t have a definition of life,” says Kevin Peter Hand, one early California morning when we speak via video. “We don’t actually know what life is.”

He says that in between sips of coffee, as though it were perfectly obvious.

But scientists must really get bored — even annoyed — by journalists repeatedly asking how their fundamental research in space can be applied in the real world. It is a question worth asking, however. Especially when they tell you that they are looking for a “second origin of life.” You just have to ask why.

Fortunately, Hand, who heads NASA’s Ocean Worlds Lab, is charming and gentle as he explains his fascination with what he calls “alien oceans” both on Earth and on distant water worlds, like Jupiter’s moon, Europa, Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, or Triton, a “bizarre” object that rotates in the opposite direction from its host planet, Neptune.

“We have numerous hypotheses for how life originated on Earth,” says Hand. “For instance, it may have originated in the hydrothermal vents of our ocean, or in warm tide pools on the continents of an ancient Earth, or perhaps it originated from spark discharge from lightning in the atmosphere and precipitating organic compounds glued together to form life… But nothing has so far crawled out of the lab.”

Alien Oceans Here and There

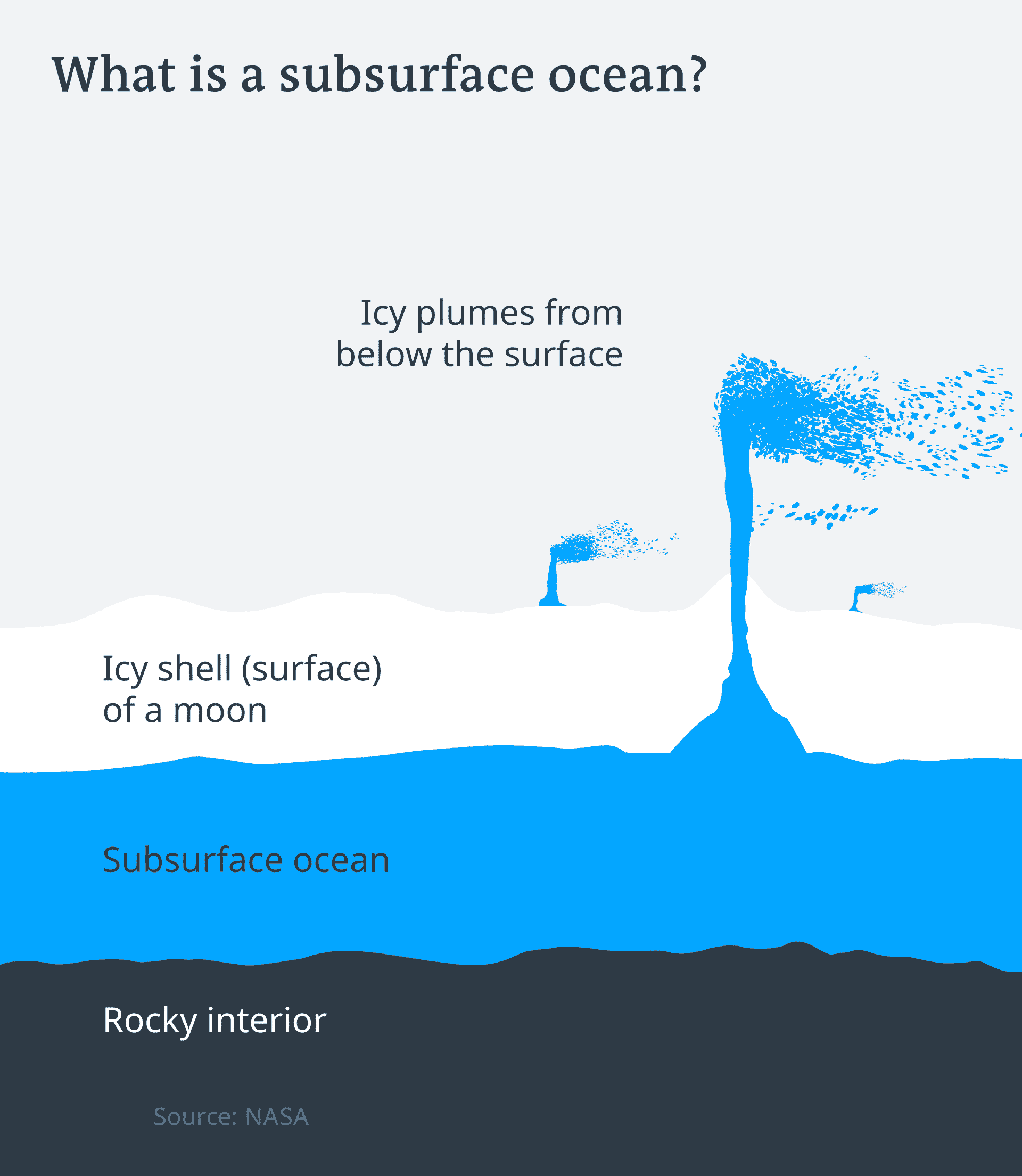

Europa, Enceladus, and Triton are just three of over 200 moons in our solar system. But they are special moons. They seem to have live, liquid water environments below the surface — also known as subsurface oceans — under an icy shell.

“These are global liquid oceans covered with ice,” says Hand. “And if we go to Europa or Enceladus, these worlds where hydrothermal vents could exist, but where no continents exist, and there’s no atmosphere, and if we found life, that would almost certainly point to an origin of life in hydrothermal vents.”

And that may then tell us more about life on Earth.

Hydrothermal vents are found at extreme depths of around 6,000 kilometers (3,728 miles) in vast trenches below the surface of Earth’s own ocean.

Not so long ago, those trenches were believed to be too dark for any life to exist. But through oceanographic research and commercial prospectors trawling for rare minerals like manganese nodules, we now know that hydrothermal vents are teeming with microbial life. So, the same may be true on a distant moon.

“That’s not to say we’d be able to cross off the potential for the origin of life in tide pools on ancient Earth, but if we found life in hydrothermal vents on these moons, we would at least have another data point,” says Hand.

Biology Beyond Earth

Biology — or organic life as we know it — is perhaps the final piece in a jigsaw puzzle for space scientists.

Thanks to Galileo, says Hand, we know that the laws of physics work beyond Earth. So, too, with the principles of chemistry and geology.

“But we don’t know whether this phenomenon called life has happened a second, independent time from life here on Earth. And that’s why the question of a second origin of life is so compelling,” says Hand.

And it’s vital that that second origin of life is discovered — if at all — on planets, moons and other celestial bodies deep in the solar system, bodies that are too far away for any Earthly life to have reached or “contaminated” what may, or may not, be there.

“It would be hard for an Earth rock to get out there with Earth microbes and seed those oceans with DNA-based life,” says Hand. “So, if we find life on these worlds, they will represent a separate, independent origin of life and, as such, that will tell us about the diversity of life, not just in our solar system, but in the universe as a whole.”

The Europa Clipper

Hand’s focus for now is Jupiter’s moon, Europa. One of his current projects is the Europa Clipper mission, which will perform about 45 so-called “flybys” of the moon.

Its launch date has yet to be decided. But the plan is for the Europa Clipper to take hi-resolution images of the moon’s surface on a scale of between 50 centimeters per pixel and tens of meters per pixel.

It will look for organics, like salt.

It will have an ice penetrating radar onboard, and spectrometers that could “taste” any plumes erupting out of Europa.

“It will fly through the plumes and capture some of that material so we can analyze it directly. That will be phenomenal, but it won’t get us down to the surface,” says Hand. So, they are working on another mission that would land on Europa, too.

Trident for Triton

Meanwhile, NASA’s Discovery Program has two further outer solar system moon missions under consideration. One of those missions is called Trident. And if it’s selected to move forward, the mission will investigate Neptune’s moon, Triton.

Trident would launch in 2026 for a 12-year journey to Triton. The last spacecraft to study Triton was Voyager 2, which launched in 1977. It got to within 40,000 km of Triton, whereas Trident would get as close as 500 km on two flybys.

“Voyager gave us pictures that let us see geysers and plumes on Triton and that was 30 years ago — 50 years before Trident,” says Yohai Kaspi, a professor of atmospheric dynamics and planetary science at the Weizmann Institute in Israel. “But with today’s technology and imaging, we can do much better.”

Kaspi and his colleagues are contributing a special clock to the project, with which they hope to measure the density and temperature of Triton’s atmosphere.

The clock is called an Ultra-Stable Oscillator (USO).

It’s a basically quartz clock, like a quartz wristwatch, but it’s kept it at a very stable temperature to protect it from all the temperature variations in space.

“You hold it in a little oven, literally a tiny oven, with a stable temperature of one milliKelvin,” says Kaspi, “and that gives us an accurate time frequency.”

The spacecraft will have a radio link to Earth for the purpose of Kaspi’s experiment and for general use, such as navigation. It will be a constant signal.

But the speed at which that signal travels back to Earth will change as the spacecraft enters and moves through Triton’s atmosphere. The atmosphere is almost a filter through which the signal will have to pass. Measuring and comparing the difference in time it takes the signal to travel to Earth will allow scientists to measure thickness of Triton’s atmosphere and build a profile of the moon’s atmospheric temperature.

How Do Moon Oceans and Their Atmospheres Interact?

Kaspi says Triton’s atmosphere makes it unique. “Enceladus is too small to have an atmosphere and Europa barely has an atmosphere,” he says. “Triton’s atmosphere is not as dense as the one on Earth but it’s enough of an atmosphere to transport material around. And in addition to that, it’s likely that Triton was not even formed in our solar system. So, it’s a real opportunity.”

If the mission goes ahead, it may also be an opportunity to understand more about the interaction between subsurface oceans, or the “interior” of such moons, and their atmospheres. Because atmospheres are just as important for maintaining life and water is for originating life.

“We see these plumes coming from the interior, and they are then transported by the atmosphere. We see these active geysers and then these streaks on the planet, and they’re all in the same direction,” Kaspi says. “So, you would assume that there is a wind going from one side to the other. Voyager observed that. But that is about as much as we know.”

What we don’t know, says Kaspi, is how much of Triton’s atmosphere originated from the interior, or whether the subterranean ocean can communicate or interact much with the outside.

The instruments on Trident are designed to find out how the whole system works together. They may even get us a little closer to that elusive definition of life itself.

“I hope that maybe 400 years from now our descendants will be able to point to innovations and discoveries that we made and go, ‘Wow, can you believe they argued about the importance of searching for life beyond Earth and its application?'” says NASA’s Kevin Hand.

“And perhaps they will be able to laugh about that in the same way that we look at Galileo and say: ‘Of course, Galileo’s work was pivotal in changing the way we think about the universe’ — and everything that cascades from that, right down to the computer conversation that we’re having now.”

Message received.

Reposted with permission from Deutsche Welle.

- GOP to NASA: Forget Climate Science, Focus on Space - EcoWatch

- Trump Signs Executive Order to Mine the Moon for Minerals ...

- 'Shockingly Stupid': Trump to Eliminate NASA Climate Research ...

- Water May Have Originated on Earth, Study Finds

- Scientists Detect Possible Sign of Life on Venus - EcoWatch

- Jupiter and Saturn Will Form ‘Double Planet’ This December for the First Time in 800 Years - EcoWatch

- Looking for Evidence of Past Life on Mars - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe