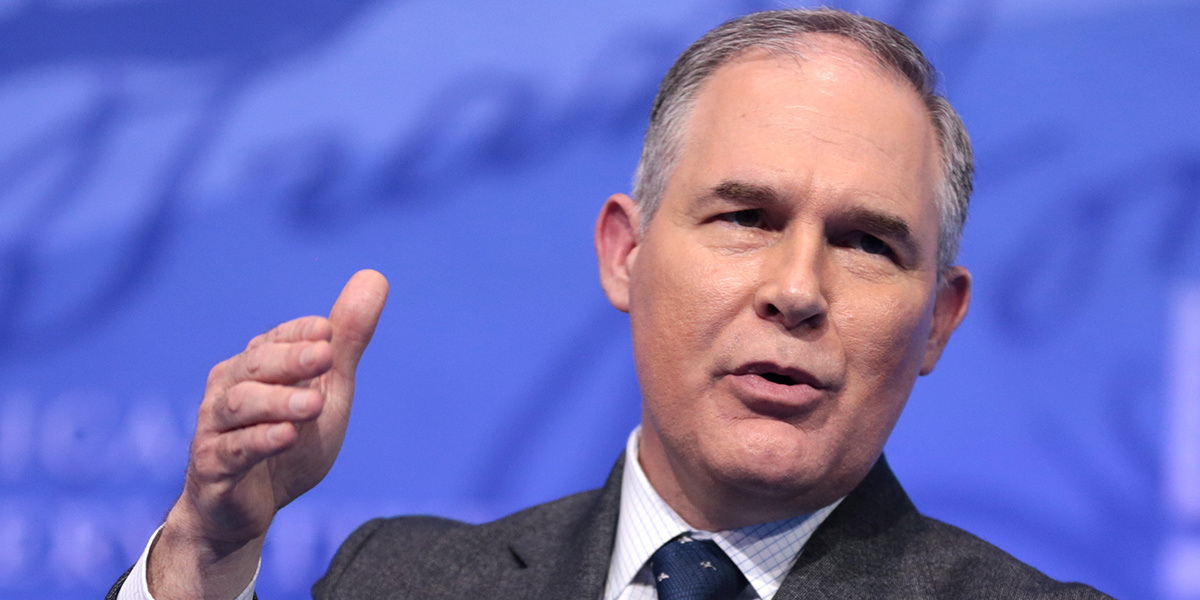

EPA chief Scott Pruitt wanted a national debate on climate change. Gage Skidmore / Wikimedia Commons

White House Chief of Staff John F. Kelly put a stop to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) head Scott Pruitt‘s plan to hold nationally-publicized debates on the science of climate change, The New York Times reported Friday.

According to the Times, Pruitt had been developing the idea since before June 2017, when he told the board of the American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity that the EPA was working on a “red-team-blue-team” challenge to mainstream climate science.

Anonymous sources familiar with the matter told the Times that President Trump had liked the idea, but Kelly and other White House officials worried about its political consequences.

“Their main concern was that a public debate on science—particularly on an issue as politically charged as the warming of the planet—could become a damaging spectacle, creating an unnecessary distraction from the steps the administration has taken to slash environmental regulations enacted by former President Barack Obama,” Lisa Friedman and Julie Hirschfeld Davis wrote in the Times.

Pruitt had reportedly aimed to issue a press release about the proposed debates in November, but Kelly prevented him. He ordered the idea be postponed until White House officials and cabinet secretaries could meet to discuss it, but that particular meeting never transpired.

Instead, in a Dec. 13 meeting of senior White House officials, including two EPA representatives, Kelly’s deputy Rick Dearborn declared the idea “dead.”

The red-team-blue-team concept was first floated by Steven Koonin, a physicist and Energy Department undersecretary during the Obama administration, in an opinion piece for The Wall Street Journal in April 2017. Koonin based the idea on an exercise used by the “national-security community” as a risk assessment strategy; he proposed that a “Red Team” of scientists would critique a report meant to inform policy on climate change, such as the U.S. Government’s National Climate Assessment, and a “Blue Team” would then defend it.

Once Pruitt picked up on Koonin’s idea, scientists criticized it for misrepresenting the amount of internal critique already integral to the peer-review process.

“Scientists are already spending most of their time trying to poke holes in what other scientists are saying,” Ken Caldeira, an atmospheric scientist at the Carnegie Institution for Science, wrote in an email to the Times in June. “The whole red team-blue team concept misunderstands what science is all about.”

The scientific research process has led to a 90 to 100 percent consensus among publishing climate scientists that human activity is causing climate change, according to one study published in Environmental Research Letters in 2016.

A public debate questioning that consensus would likely have political consequences beyond pure spectacle. That consensus backs up the EPA’s 2009 endangerment finding, which concludes that greenhouse gases “threaten the public health and welfare of current and future generations,” and requires they be subject to governmental regulation. According to Friedman and Hirschfeld Davis’ analysis, publicly challenging climate science could be the first step in legally overturning that finding, a top priority for climate-denialist groups like the Heartland Institute.

John F. Kelly, a retired four-star general, is the rare key player on the Trump team who accepts the scientific consensus behind climate change. Although he has not spoken out publicly on the subject, he headed U.S. Southcom from 2012 to 2016 when it played a key role in helping the Pentagon strategize for the national security threats posed by rising temperatures and sea levels, The McClatchy Washington Bureau reported in August. His intervention against Pruitt might be a sign of his climate views in action.

Climate Impacts Nearly Half of U.S. Military Bases https://t.co/9BD9keUWAV @wattsupwiththat @climatecouncil @WRIClimate

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) February 3, 2018

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe