Critically Endangered Orangutan Species in Indonesia Gets Reprieve as Controversial Dam Delayed

Indonesia's dam project might devastate the most critical areas of the Batang Toru ecosystem and drive the Tapanuli orangutan to extinction. Tim Laman / Wikimedia Commons / CC by 4.0

By Hans Nicholas Jong

Construction of a hydropower plant in the only known habitat of a critically endangered orangutan species on the Indonesian island of Sumatra might be delayed for up to three years due to COVID-19 and funding issues.

Muhammad Ikhsan Asaad, who oversees the project for state-owned utility PLN, said the Batang Toru plant was supposed to start operating in 2022, based on the agreement between PLN and project developer PT North Sumatra Hydro Energy (NHSE).

“But it might be delayed to 2025, mainly because the drawdown from lender Bank of China is stopped due to environmental concerns as well as COVID-19,” he said.

In construction, a drawdown refers to a situation in which a company receives part of the funding necessary to complete a project, and the rest of the funding might be disbursed gradually over the course of the project.

The project is estimated to cost .68 billion, financed through equity and loans.

NSHE initially sought loans from funders like the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB). But following the description of a new orangutan species, the Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis), in the Batang Toru ecosystem in northern Sumatra in 2017, environmentalists have called for the project to be stopped or at least halted to allow for an independent scientific study of its impact on the newly known species.

They say the project might devastate the most critical areas of the Batang Toru ecosystem and drive the Tapanuli orangutan to extinction. Only 760 of the great apes are estimated to survive in a tiny tract of forest less than one-fifth the size of the metropolitan area that comprises Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta.

Shortly after its description, the Tapanuli orangutan was categorized as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List due to its decreasing population trend — down by 83% in just three generations — and heavily fragmented distribution.

The IFC and ADB subsequently distanced themselves from the project. And in March 2019, the Bank of China, which is also involved in financing the project, said it had “noted the concerns expressed by some environmental organizations” and promised to carefully review the project. It has not issued any further public updates, leaving the funding for the project uncertain.

NSHE has previously confirmed that the project’s funding was in doubt as a result of campaigns against the dam.

PLN director Zulkifli Zaini said environmental issues were among the reason why the project might be delayed.

“It is true that the project faced hurdles from NGOs over environmental issues,” he said. “There are apes and other [animals] there.”

The coronavirus outbreak has also proved to be a setback, with the work on the hydropower plant put on hold since January after construction workers from Chinese state-owned contractor Sinohydro, who had gone home for the Lunar New Year holiday, were barred entry back into Indonesia over health concerns.

NSHE has submitted a request to PLN, as the buyer of the plant’s power, to push the start of the dam’s operation to 2025. But the utility said a decision hadn’t been made yet.

“NSHE and PLN are still in the stage of discussion or collective review regarding the target of the Batang Toru hydropower dam operational target,” NSHE spokesman Firman Taufick said. “Whatever the result of the discussion between NSHE and PLN, we will always follow the policy and direction from PLN.”

A decline in electricity consumption as a result of suspended economic activity during the pandemic is another factor that could delay the project, according to Riza Husni, chairman of APPLTA, a national association of hydropower plant developers.

Dana Tarigan, the head of the North Sumatra chapter of the Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi), said he hoped PLN would take into account the environmental concerns over the project in making a decision.

“We’re hoping PLN could see the rejection well,” he told Mongabay. “There’s not only the problem with COVID-19, but also rejections from many parties, whether it’s because of [the potential impact on] the orangutan and other biodiversity, or on the safety of the people [living in nearby areas].”

Dana said Walhi had staged a protest in 2018 against the project outside the offices of PT Pembangkit Jawa Bali (PJB) Investasi, a subsidiary of PLN that serves as the project sponsor and a shareholder in the Batang Toru power plant.

The protesters demanded that PJB Investasi, which holds a 25% stake in NSHE, to withdraw from the project.

Dana also urged PLN to take into account a recent fact-check report by the IUCN that analyzes the many contradictory claims being made about the project’s potential impacts, specifically assertions made by NSHE.

The Batang Toru River, the proposed power source for a Chinese-funded hydroelectric dam. Ayat S. Karokaro / Mongabay-Indonesia

Fact-Checking

The report identifies several significant claims found in NSHE’s publications or press releases as being inaccurate or misleading.

“In at least ten cases, assertions made in public-facing NSHE literature or on the NSHE website are found to be inconsistent with findings presented in earlier impact assessments conducted on behalf of NSHE,” the report says.

The report also finds other claims made by NSHE contradict findings in peer-reviewed literature and technical reports.

“Some of these relate to the most controversial aspects of the project such as its impact on the Tapanuli orangutan and the ecology of the Batang Toru river, the demand for the power that the plant would produce, and the project’s compliance with international investment standards,” the report says.

Emmy Hafild, a senior adviser to NSHE’s chairman, said the report mistakenly accounted for the whole project permit area, instead of its actual footprint, to assess its potential impact on the orangutan. She also said the permit area referred to in the report was based on the company’s permit area during exploration stage, which was larger than the current permit area post-exploration.

“The IUCN fact check report is clearly wrong,” Emmy said. “The report uses data that’s already outdated and this is the location permit, not the footprint of the project.”

Serge Wich, the co-vice chair of the IUCN primate specialists’ section on great apes (SGA) and one of the researchers who described the Tapanuli orangutan, said it’s clear the IUCN report refers to the whole permit area in fact-checking the company’s claim.

“[A]nd we have always said that this indicates the maximum impact,” he told Mongabay.

Wich said that while the project might not occupy the full area, its impact on the orangutan could still be devastating due to the location of the project, which lies at a key location for connectivity between the orangutan’s subpopulations, split up across three separate blocks: west, east and south. By locating the dam there, the project would jeopardize that connectivity, he said.

Emmy denied the location of the project would impact the potential for a future forest corridor linking the western and southern populations of the orangutan.

“The footprint of the project has been checked by our friends [researchers] and it will not disturb the corridor,” she said.

Wich said that might not be the case, as the latest Batang Toru ecosystem map provided by NSHE clearly shows that the project area is “a long wall-like structure cutting those three areas from each other.”

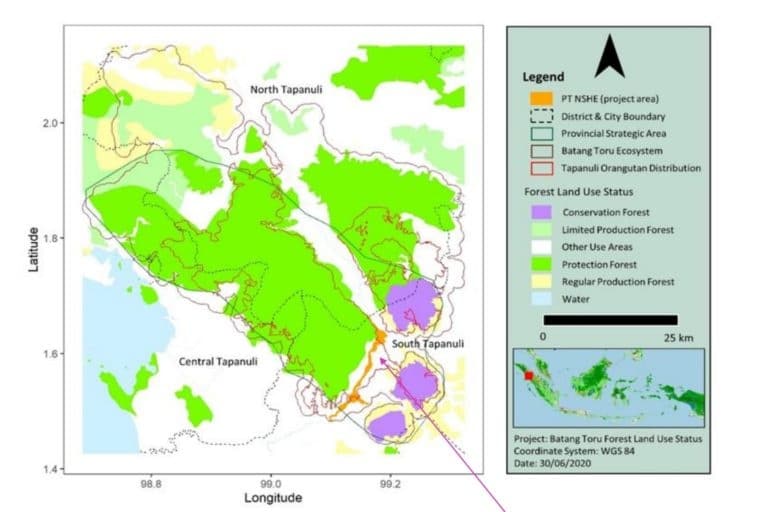

The map of the Batang Toru ecosystem and the hydropower dam project area. PT North Sumatra Hydro Energy (NSHE)

Didik Prasetyo, an orangutan researcher at Jakarta’s National University, who conducted a study on the project, said he’s confident the hydropower dam will not threaten the orangutan as long as NSHE sticks to his recommendations. Among them: limiting the amount of traffic passing over the project’s roads; and designing the project’s overhead power lines to allow the orangutans to travel safely beneath them.

“If it’s safe, then [the orangutans] will not be scared to briefly walk on the ground [to cross from one population to another],” Didik said. “The width of the road is not too dangerous for the orangutans if there’s no one passing on the road. So we’re recommending the traffic be limited to particular hours.”

He said rehabilitating impacted areas is also crucial.

“We’re recommending to the company that there are three areas that will be impacted significantly if the company doesn’t manage [the project] sustainably,” Didik said. “So we recommend these most-threatened areas to be restored as soon as possible.”

He said there are 273 hectares (585 acres) of orangutan habitat in the project area, of which 84 hectares (207 acres) will be used as a location for permanent buildings by the company. The remaining 189 hectares (467 acres) will be reforested, he added.

NSHE said it will offset permanent forest loss caused by the project by planting trees in other areas, while temporary forest loss will be restored.

The IUCN report, however, says restoring affected areas might not be feasible. NSHE literature identifies heaps of dug-up dirt as the areas intended for restoration, but the IUCN says this might not be realistic because these areas consist of large amounts of unconsolidated material.

“The material is from underground and is potentially sterile to rehabilitation efforts and/or volatile to erosive processes,” the report says.

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe