The remote beach was empty except for me and my companions. The broad expanse of sea was empty, too and I squinted at the horizon, looking for a human shape. This was two years ago, deep in southern Chile and five of us had just descended the bottom section of the Pascua—a burly, glacier-fed river—by kayak. We were at the Pascua’s mouth, where it empties into a fjord and we were planning to head through the fjord to the small town of Caleta Tortel. Two of the kayakers from our party, Lisa and Roberto, had paddled ahead until they disappeared amid the chop. Now, I was trying to find them in this gray-green world.

Seeing no sign of them, I walked back to the riverbank and kneeled for a drink of agua dulce—freshwater. Cold slid down my throat. The air smelled sweet, of mist and storms and clouds were slung low above the water. Waves jostled and splashed and I breathed deeply, readying myself for what I knew I had to do next: paddle through the tumult that Lisa and Roberto had just vanished into.

There was nothing for the three of us left on the gravel bar to do but load into our boats and point them toward the inlet. The other lives we all lived—an existence with things like showers and email and beds—had become laughably unimportant. Our needs were immediate and self-evident. Stay alive, stay dry, stay together and keep going. Or turn back. But we had no intention of turning back. We gripped our paddles and pushed off the bank.

Where the river hits the sea, we hit the waves—heaving pyramids of whitecapped water that splashed over our spray skirts. My boat partner and I counted aloud to pace our strokes—one, two, three, four—as we dug our paddles into the dark water, hoping that if we paddled hard enough for long enough, we’d stay upright and make it to the nearest shore. Our kayak, about 17 feet long, rose onto the swells, hung in midair, then slammed back down. I clenched my paddle tighter. My forearms stiffened and ached. The land, the water, the weather—all of it became real and close. Although nerve-racking, this was the kind of intensity I lived for. It pulled me into the present and put all of me to work.

We aimed our boat for a beach that we could see between the waves. As we got closer, I spotted two life-jacketed figures pulling brightly colored plastic boats ashore. Lisa and Roberto had made landfall.

Why was I there, paddling as hard as I could on those stormy seas? There’s more than one way to answer that question. The Pascua is in a region of Chile called Aysén. I’d spent the past couple of years there doing research on a proposal to build five large dams, two of which would be on the Pascua. During the course of that project, I had learned a lot about river flows, hydropower and electricity transmission lines. But I wanted to know the river that I had thought about so much in a more intimate way. Before the Pascua’s power turned to megawatts, I wanted to feel its current against my skin.

I was also in Aysén for less practical reasons. Like many others before me, I’d been drawn by the idea of Patagonia: a place where wind and weather ruled, granite spires rose from the Earth and teal rivers curled through a trackless steppe. Parts of Aysén are practically uninhabited, with less than three people per square mile—a lower population density than that of the Sahara Desert or Mongolia. I’d hitchhiked through the region, kayaked its rivers and explored its valleys, trying to get closer to the place I’d been so fixated on. The ecological philosopher Arne Naess wrote that mountaineering is a way to participate in a mountain’s greatness. In the same vein, everything I did in the far south was part of my attempt to participate in the greatness of that landscape.

The Pascua encapsulates all that is wondrous about Patagonia. Other rivers in the area, like the Baker, are strewn with ranches, but very few gauchos—South America’s version of cowboys—live along the Pascua. Those who do first arrived in handmade wooden rowboats. To get up the river before motorboats, the gauchos had to stand on the thickly forested banks of the Pascua and pull their boats (which were sometimes full of lambs) upstream with ropes. A spur road from the dirt highway did not arrive until 2006. The Pascua was remote, powerful, isolated—a force to be reckoned with. As a few friends and I talked about a potential trip on the river, we began referring to it as “the wild and unknown Pascua.”

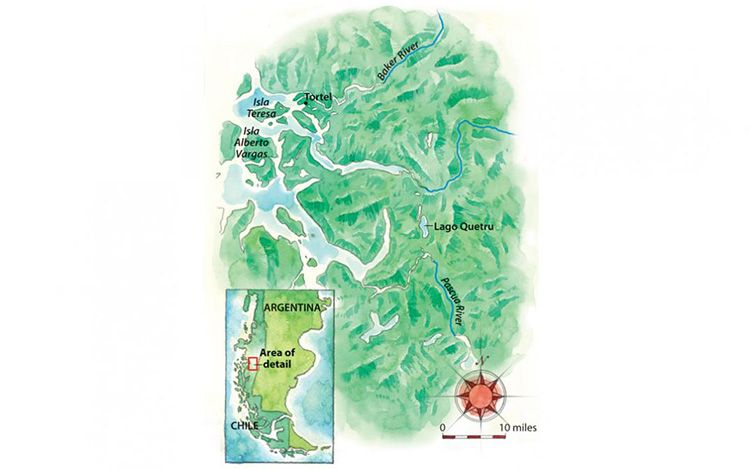

So, we decided that in February 2014 we would kayak the lower Pascua from near Lago Quetru to the shores of Tortel. Our crew would be Weston Boyles, a then-27-year-old Colorado native; Tyler Williams and Lisa Gelczis, husband-and-wife guides from Flagstaff, Arizona; and Roberto Haro, a middle-aged gym teacher from the town of Cochrane who taught local kids how to whitewater kayak. The four of them had met through an organization Weston started, Rios to Rivers, which had facilitated an exchange between some of Roberto’s teenage kayakers and some American kayakers to paddle the Baker and Colorado Rivers while learning about the effects of dams.

Simply getting ready for the trip was challenging. There were no reports from other paddlers or even any detailed maps. So we huddled around a laptop in Roberto’s kitchen, scrolling through satellite images to sketch a route.

Maps of the area show a shredded coastline where the continent encounters the sea. Islands are splattered across bays and fjords slice into the mainland, carvings left over from the last ice age. Patagonia’s topography is similar to that of Southeast Alaska and Norway, except with more places where glaciers meet the sea.

The journey promised heavy rain, cold temperatures and high winds. Friends of ours could not understand why we would suffer through it. When we told people in Cochrane that we would kayak from Lago Quetru to the mouth of the Pascua, then up the coast to Tortel, one person asked, “Do you want to die?”

I struggled to explain why we wanted to go there. I often felt like using the clichéd response: “If you have to ask, you’ll never understand.” What drives anyone on this kind of quest? For me, it came from a desire to be part of something giant and wild, a yearning to participate in something beautiful. To do that fully, I needed to give up control.

At the beginning of our journey, on the banks of the Pascua, we had packed our boats and loaded them into the water. The river was so wide, it often looked like a moving lake. Boils wrinkled the surface. The water split into braids around sandy shoals and bent sharply around unnamed mountains. We paddled up creeks and made sandwiches with manjar (Chile’s version of dulce de leche) on our spray skirts. On our second day, we reached the Pascua’s mouth, where the river emptied into the fjord and where our group dispersed and came together again on that wind-whipped beach to wait out the bad weather.

We took naps and ate snacks and read books, then eventually set out again. Frothing water exploded against cliffs to our left. To our right, the sea spread outward until it welded itself to a skyscape of gray clouds. No more beaches appeared on the coast. The headwind blew so hard that if we paused our paddle strokes, the Klepper went backward. I couldn’t stop to scratch my nose. Weston and I synchronized our strokes. Much of the time, we couldn’t see our friends.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe