By Jeff Masters

The first all-time national heat record of 2017 was set in spectacular fashion on Thursday in Chile, where at least 12 different stations recorded a temperature in excess of the nation’s previous all-time heat record—a 41.6 C (106.9 F) reading at Los Angeles on Feb. 9, 1944.

According to international weather records researcher Maximiliano Herrera, the hottest station on Thursday was Cauquenes, which hit 45.0 C (113 F). The margin by which the old record national heat record was smashed: 3.6 C (6.1 F), was extraordinary and was the second largest such difference Herrera has cataloged (the largest: a 3.8 C margin in New Zealand in 1973, from 38.6 C to 42.4 C).

Herrera cautioned, though, that the extraordinary high temperatures on Thursday in Chile could have been due, in part, to the effects of the severe wildfires burning near the hottest areas and the new record will need to be verified by the weather service of Chile.

Here are some of the high temperatures from Jan. 26 in Chile:

Maule Region (near the area affected by wildfires):

Cauquenes, 45.0 C

Coronel de Maule, 41.8 C

Los Despachos, 42.8 C

Santa Sofia, 43.1 C

Sauzal, 41.8 C

Maule Region (outside the area affected by wildfires):

Linares, 41.8 C

Longavi Sur, 42.3 C

Parral, 40.8 C

Bio Bio Region (near the area affected by wildfires):

Bulnes, 42.5 C

Quillon, 44.9 C

Ninhue, 43.0 C

Bio Bio Region (outside the area affected by wildfires):

Portezuelo, 41.2 C

Chillan, 41.4 C (DMC station)

Chillán Quinchamalí, 43.0 C

San Nicolas, 41.1 C

Los Angeles Maria Dolores Airport, 42.2 C

Record Heat and Extreme Drought Lead to Deadly Chile Wildfires

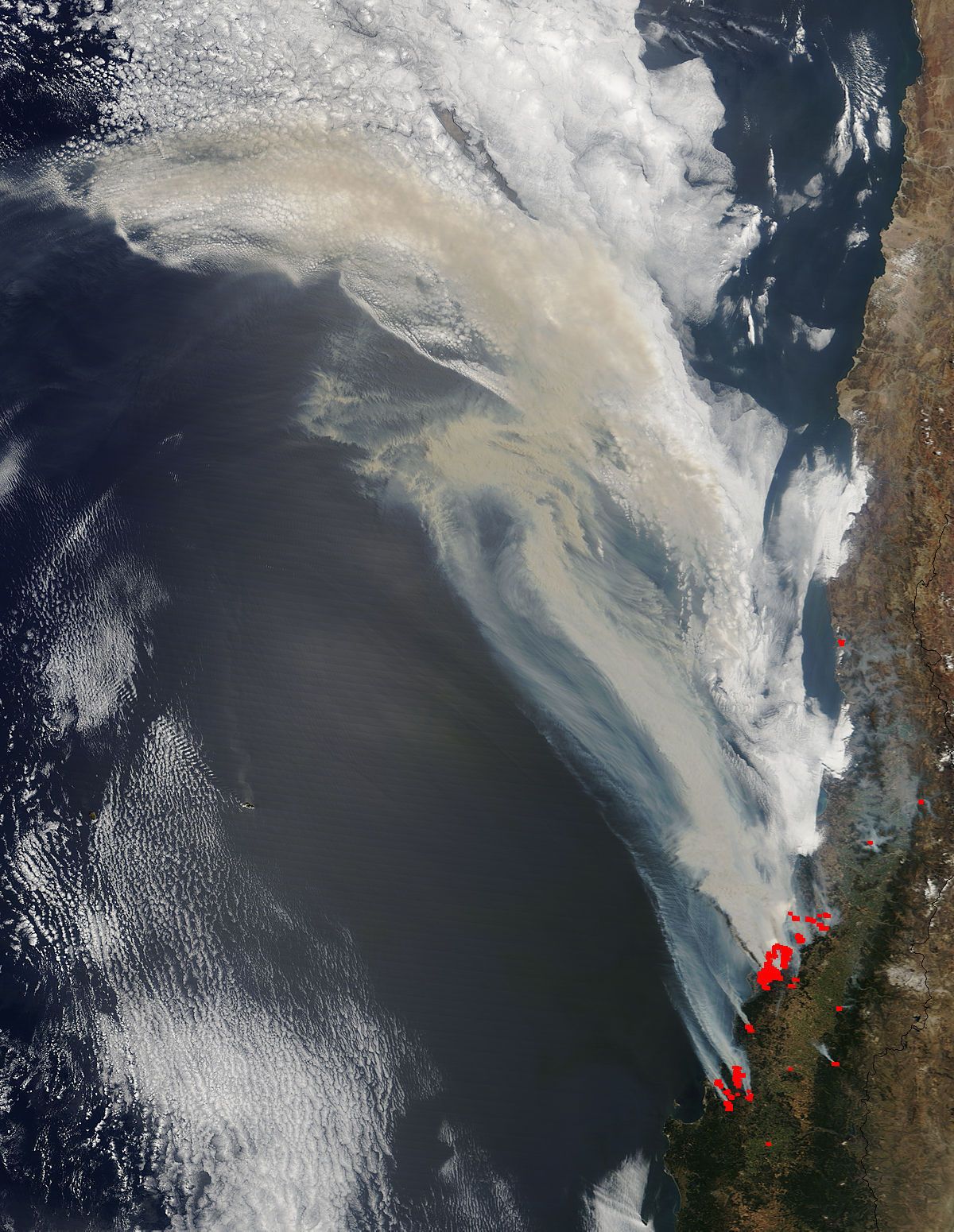

Record heat and extreme drought in Chile are contributing to their worst wildfires in decades. On Thursday, the entire town of Santa Olga was destroyed by fire, with more than 1,000 building consumed including schools, nurseries, shops and a post office.

As reported in The Guardian, Carlos Valenzuela, the mayor of the region, said: “Nobody can imagine what happened in Santa Olga. What we have experienced here is literally like Dante’s Inferno.” Authorities declared a state of emergency in Chile due to wildfires on Jan. 20 and as of Jan. 26, more than 100 fires were burning throughout O’Higgins and Maule regions.

At least ten people have been killed by the fires, including four firefighters and two policemen. According to insurance broker Aon Benfield, the fires had consumed 578,000 acres of land as of Jan. 26 and damages to the timber industry alone were estimated at $40 million. Hot, dry weather with high temperatures in the 90s are expected to continue for the next week in the Santiago area.

Chile’s Ongoing Megadrought Partially Attributed to Human-Caused Climate Change

Central Chile is enduring a decades-long megadrought that began in the late 1970s, with precipitation declines of about 7 percent per decade. According to a 2016 study by Boisier et al., Anthropogenic and natural contributions to the Southeast Pacific precipitation decline and recent megadrought in central Chile, this drought is unprecedented in historical records.

While at least half of the change in precipitation can be blamed on natural causes, primarily due to atmospheric circulation changes from the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, the authors estimated that a quarter of the rainfall deficit affecting this region since 2010 was due to human-caused climate change.

Reposted with permission from our media associate Weather Underground.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe