By Llewelyn Hughes and Jonas Meckling

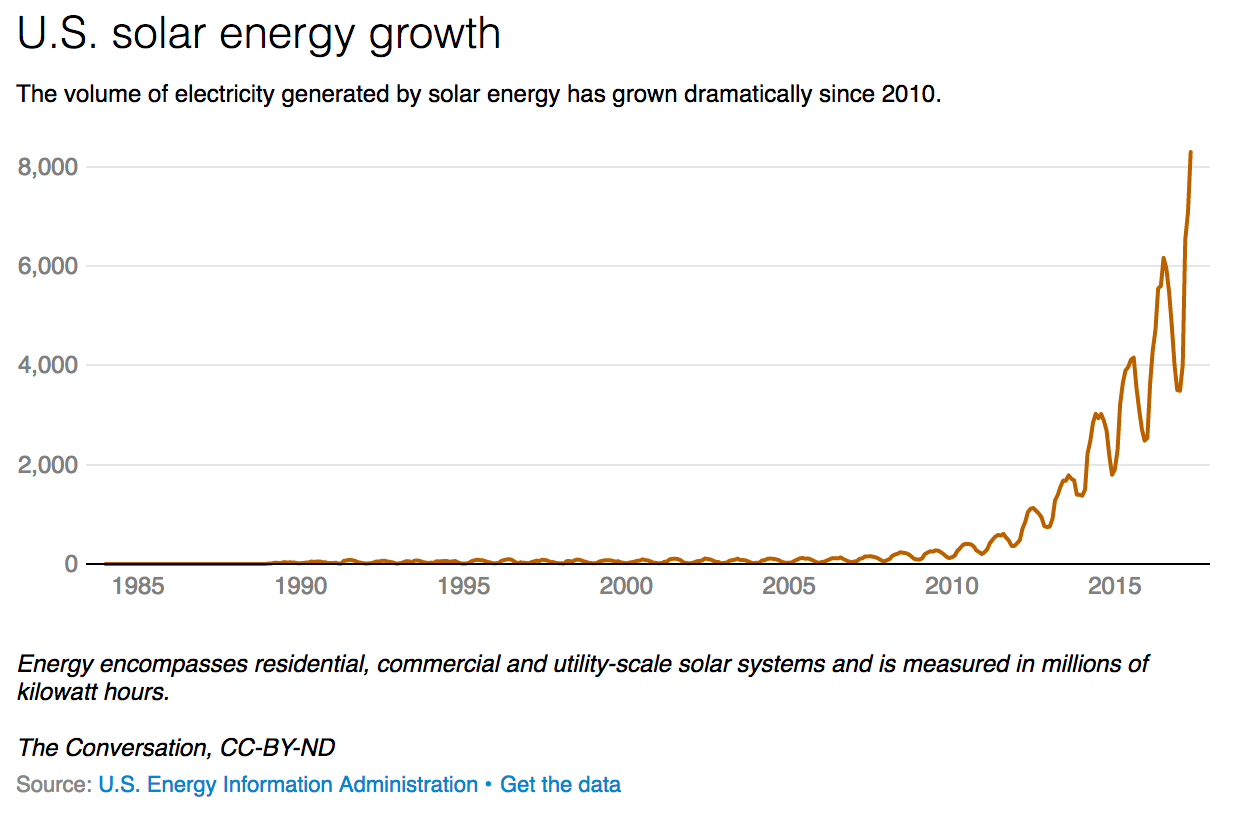

Tumbling prices for solar energy have helped stoke demand among U.S. homeowners, businesses and utilities for electricity powered by the sun. But that could soon change.

President Donald Trump—whose proposed 2018 budget would slash support for alternative energy—may get a new opportunity to undermine the solar power market by imposing duties that could increase the cost of solar power high enough to choke off the industry’s growth.

As scholars of how public policies affect, and are affected by, energy, we have been studying how the solar industry is increasingly global. We also research what this means for who wins and loses from the renewable energy revolution in the U.S. and Europe.

We believe that imposing steep new duties on imported solar equipment would hurt the overall U.S. solar industry. That in turn could discourage choices that slow the pace of climate change.

Trade Complaints

A bankrupt manufacturer has petitioned the Trump administration to slap new duties on imported crystalline silicon photovoltaic cells, the basic electricity-producing components of solar panels—along with imported panels, also known as modules.

This case follows earlier and narrower complaints filed by SolarWorld, a German solar manufacturer with a factory in Oregon, that Chinese companies were getting an unfair edge as a result of subsidies and dumping.

Due to those cases, the U.S. has imposed duties on solar panels and their components imported from China and Taiwan. The punitive Chinese tariffs averaged 29.5 percent last year, according to the Greentech Media research firm.

Suniva, a U.S. company that—oddly enough—is majority-owned by a Chinese company, lodged this complaint in April under a rarely activated 1974 Trade Act provision called Section 201. SolarWorld Americas joined in a month later.

The key difference in this new case is that it will potentially lead to tariffs on all imported solar cells and panels, rather than specific kinds from particular countries.

Suniva’s petition calls on the Trump administration to set a 40-cent-per-watt duty on cells and a minimum 78-cent-watt price for panels.

Prior to the complaint, global prices for solar panels had fallen to 34 cents a watt.

Enormous Progress

This big increase in import duties could undermine the enormous progress the industry has made in cutting the cost of solar-generated electricity. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory finds that tumbling solar module prices contributed a lot to the 61 percent reduction in the cost of U.S. household solar power systems—typically located on rooftops—between 2010 and 2017.

The Solar Energy Industries Association, which represents the sector in the U.S., calculates a blended average price that takes residential, commercial and utility-scale systems into account. It finds prices fell more sharply, dropping by more than 73 percent during that period.

Likewise, the Energy Department’s SunShot Initiative declared in September that U.S. utility-scale solar systems were already generating electricity at the competitive rate of 6 cents per kilowatt-hour—three years ahead of the program’s ambitious target for 2020. Falling costs for solar panels played a big part in helping the industry hit this milestone ahead of time.

The International Trade Commission will report on Sept. 22 whether it finds that imported cells and panels have caused “serious injury” to Suniva and SolarWorld.

If it does, the independent, bipartisan U.S. agency will hold a second hearing to explore ways to respond. Regardless of what remedies the commission recommends, the White House would get broad powers to increase the cost of imported solar cells and panels to at least theoretically protect Suniva.

Jeopardizing Jobs

Imposing duties on imported solar equipment will not help the U.S. industry as a whole. Like most experts, we believe that the remedy sought in this case will make solar power more expensive for businesses and consumers, which will reduce its competitiveness against other sources of energy.

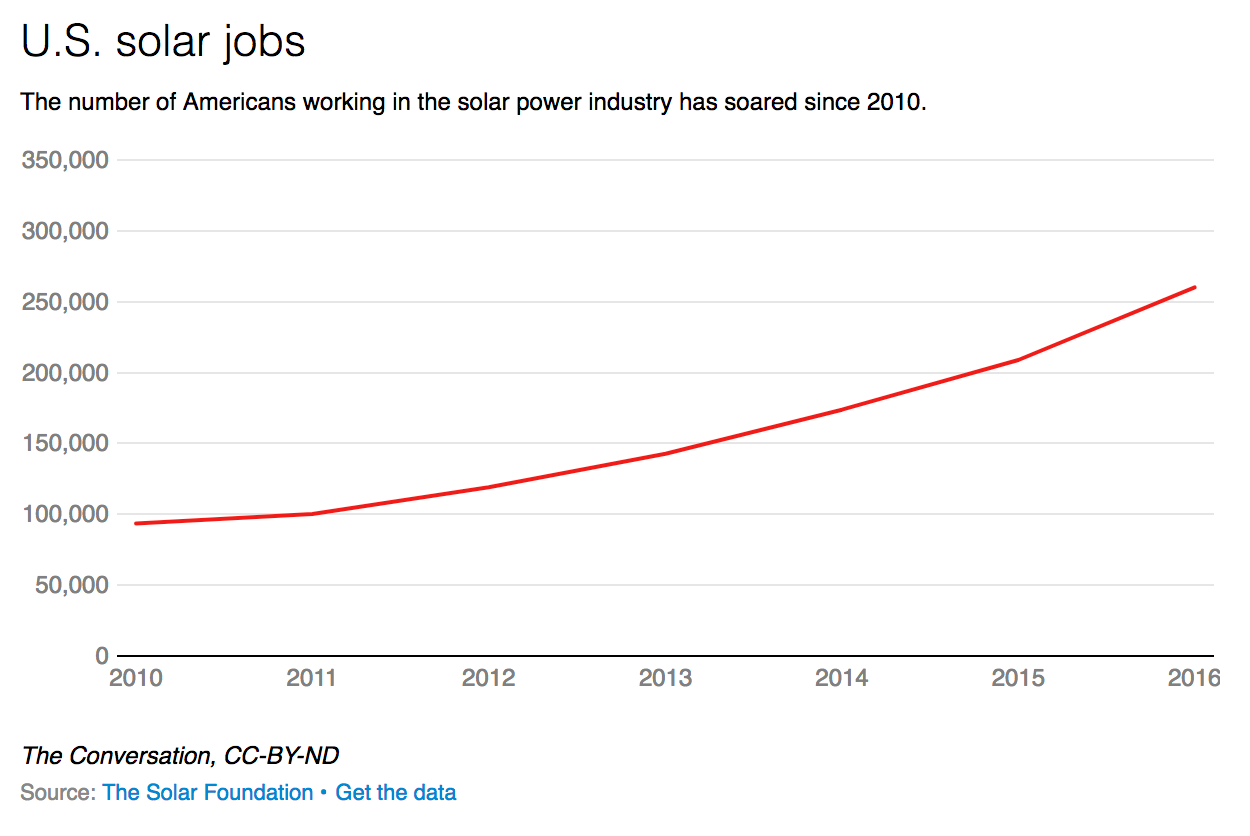

Imposing new import duties also ignores the fact that the U.S. solar industry employs an estimated 260,000 people in installation, manufacturing, sales and other related activities, according to the Solar Foundation, but only a small fraction of these workers are involved in cell production.

Protecting certain manufacturers would thus come at the costs of harming other parts of the industry. The Solar Energy Industries Association, which opposes Suniva’s petition, estimates that 88,000 jobs may be at risk. Steep duties could thus undermine the contribution solar power makes to the U.S. economy.

Solar Globalization

Along with ignoring the effects on jobs across the entire industry, the petition misses the bigger picture. Cell and panel manufacturing composes a small part of a much larger industry that takes advantage of the global manufacturing base.

The rise of China as a solar manufacturing hub is an integral part of what has helped drive costs down for installation companies and consumers around the world. Lowering the cost of solar power systems makes solar energy more competitive against more carbon-intensive sources of electricity, including coal-fired power plants.

The growth of solar energy is one factor helping many U.S. states reduce their energy-related greenhouse gas emissions.

Experts disagree about how much the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the Paris agreement on climate change matters, particularly as states like California continue to work hard on reducing their carbon footprints.

But there is no debate over whether imposing duties on imported solar cells and panels would hinder the growth of renewable energy in the U.S.—reversing climate progress.

Timeline and Punishment

Section 201 cases differ from more standard trade complaints because they do not require a determination of unfair trade practices. They also open the door to broader trade restrictions to remedy the perceived problem in a given industry.

If the International Trade Commission finds that imports have injured domestic companies, it’s expected to give the White House its recommendations by Nov. 13. Trump will probably respond within 60 days.

It took decades of research and investment to drive down the cost of solar power to the point where it is competitive with conventional sources of electricity. Should these latest trade woes increase the cost of going solar, it would be likely to kill domestic jobs and slow progress toward cutting greenhouse gas emissions across the nation.

Llewelyn Hughes is an associate professor at the Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University. Jonas Meckling is an assistant professor of Energy and Environmental Policy, University of California, Berkeley. Reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe