Saving the Ozone Layer 30 Years Ago Slowed Global Warming. Can Similar Cooperation Now Solve the Climate Crisis?

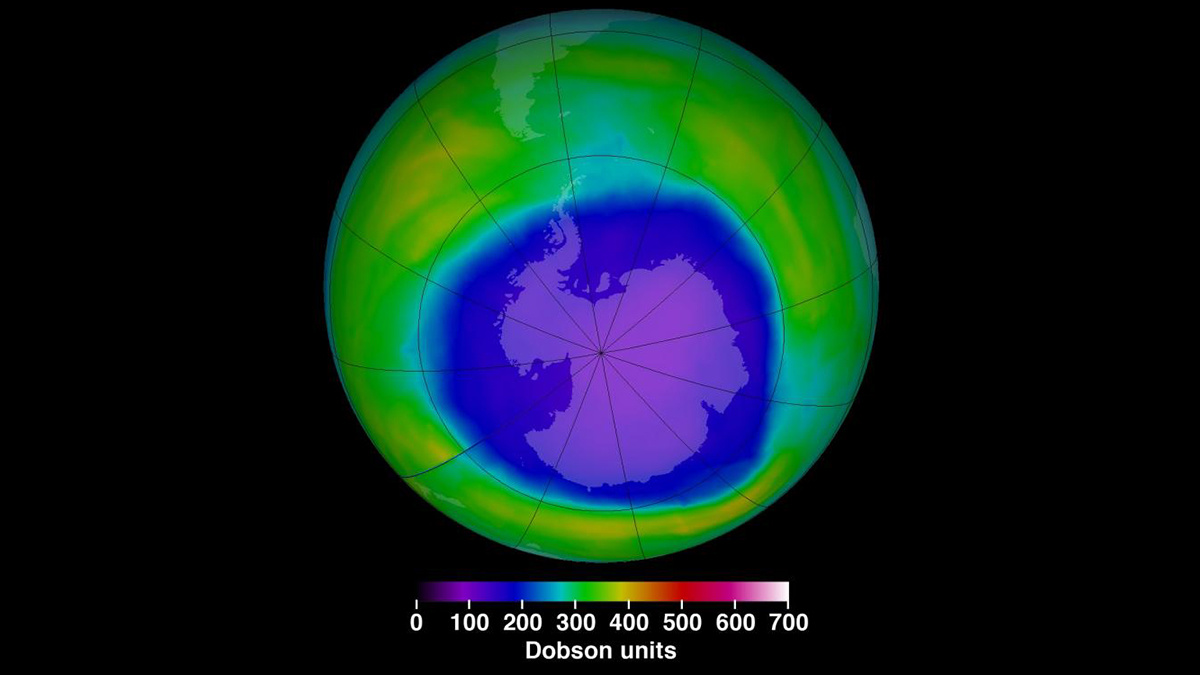

A NASA image showing the ozone hole at its maximum extent for 2015. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

The Montreal Protocol, a 1987 international treaty prohibiting the production of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to save the ozone layer, was the first successful multilateral agreement to successfully slow the rate of global warming, according to new research. Now, experts argue that similar measures may lend hope to the climate crisis.

“By mass CFCs are thousands of times more potent a greenhouse gas compared to CO2, so the Montreal Protocol not only saved the ozone layer but it also mitigated a substantial fraction of global warming,” said lead author of the paper Rishav Goyal.

Research published in the journal Environmental Research Letters suggests that in addition to slowing today’s global temperatures, the Montreal Protocol also kept the planet an average of 1 degree Celsius – and as much as 4 degrees Celsius in the Arctic – cooler than it would have been otherwise. The protocol was not only a “major success” in repairing the stratospheric ozone hole, but the researchers note that it has reduced global warming by as much as a quarter and has helped to substantially mitigate anthropogenic climate change both today and into the future.

“Remarkably, the Protocol has had a far greater impact on global warming than the Kyoto Agreement, which was specifically designed to reduce greenhouse gases. Action taken as part of the Kyoto Agreement will only reduce temperatures by 0.12°C by the middle of the century – compared to a full 1°C of mitigation from the Montreal Protocol.”

The stratospheric layer in the ozone absorbs harmful ultraviolet radiation from the sun and faced an emergency in the 1980s when researchers discovered CFCs were causing a “hole” that was inhibiting its effects, according to NOAA. The U.S. Department of State reports that international efforts to reduce the impacts of CFCs and protect the ozone layer are expected to result in the avoidance of more than 280 million cases of skin cancer, 1.6 million skin cancer deaths, and more than 45 million cases of cataracts in the nation alone by the end of the century.

“Montreal sorted out CFCs, the next big target has to be zeroing out our emissions of carbon dioxide,” said study co-author Matthew England of the University of New South Wales. An editorial written by The New York Times agrees, arguing that such a solution is possible if the world responds “with similar resolve” in dealing with greenhouse gas emissions largely responsible for climatic changes the world is seeing, but the issue is not quite as tangible as other environmental threats like clean water, smog and the ozone hole.

“Climate change, by contrast, has for a long time been seen as remote, something for future generations to worry about, and in polls has appeared far down on the list of voters’ concerns,” writes the publication. “In addition, there were no relatively expeditious technological fixes for carbon emissions, as there were for fluorocarbons, and as there were for the pollutants addressed in the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments …”

International movements like those led by teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg are bringing awareness to the current climatic state while governing bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and World Health Organization are building policies to address health, wellness and infrastructure concerns associated with a changing planet.

The study authors write that the success of the Montreal Protocol demonstrates that international treaties to limit greenhouse gas emissions not only work, but they can impact climate in “very favorable ways” and help to “avoid dangerous levels of climate change.”

- Ozone Depleting Gas Declines After Rising For Years - EcoWatch

- UN: Healing Ozone Layer Shows Why Environmental Treaties Matter

- 'Ozone Friendly' Chemicals Are Polluting the Environment - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe