New IUCN Green Status of Species to Highlight Conservation Wins and Potential

A Gray wolf (Canis lupus). Stian Olsen / Flickr

By Elizabeth Claire Alberts

The California condor has been teetering on the brink of extinction for decades. When the species was first assessed in 1994 for the IUCN Red List, the global authority on the conservation statuses of species, it was listed as “critically endangered.” Nearly 30 years later, its status has not changed. But this doesn’t tell the whole story.

Conservationists have actually been working hard to keep the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) alive with captive breeding and reintroduction efforts. “They would be extinct without conservation by now,” Claudia Hermes, a Red List researcher at BirdLife International who has worked on the California condor listing, told Mongabay. “But with conservation, they actually respond fairly well.”

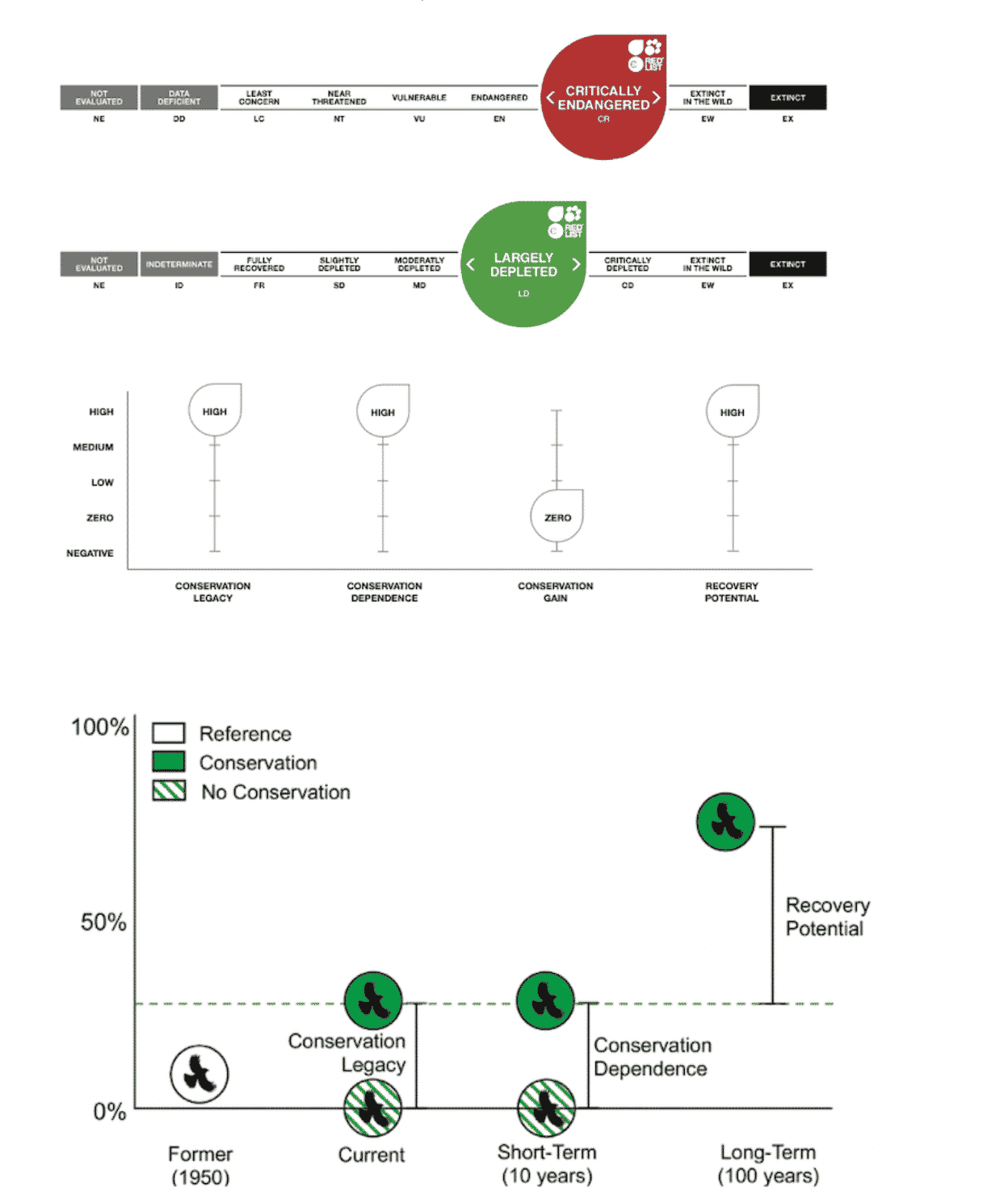

Now, a new addition to the IUCN’s Red List — the IUCN Green Status of Species — illustrates the condor’s positive response to conservation efforts, despite its critically endangered status, and its high recovery potential if these efforts are maintained.

“The Green Status really fills this gap because it tells us that despite the fairly high extinction risk that we still have this hope,” Hermes said.

The preliminary green status for the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus). IUCN

A new paper published July 28 in Conservation Biology introduces the IUCN Green Status as a new assessment framework that provides information about the ecological functionality of a species within its range, and also how much a species has recovered due to conservation efforts. A team of more than 200 international scientists from 171 institutions presented preliminary Green Status assessments for 181 species, ranging from the pink pigeon (Nesoenas mayeri) to the gray wolf (Canis lupus) to the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis).

“It’s providing a more nuanced picture of what’s going on with a species and that’s going to provide information that’s really important for conservation planning and also measuring and celebrating the impact of past conservation,” lead author Molly Grace, a researcher at the University of Oxford who led the development of the IUCN Green Status, told Mongabay. “The Red List is a wonderful tool, but when we try to use it beyond what it was made to do, which is to measure extinction risk, then we sometimes get answers that are a bit misleading or don’t tell the full story.”

The IUCN Green Status will classify species into nine recovery categories that will use historical population levels to indicate if a species has been largely depleted from its range or if it is nearing recovery. The assessment framework will also measure the impact of past conservation efforts, species’ reliance on conservation action, and how much a species could gain in the next 10 years due to conservation action. It also offers a long-term view of species’ recovery potential over the next 100 years.

A pink pigeon (Nesoenas mayeri) photographed in its native Mauritius. Sergey Yeliseev / Flickr

Sometimes a species’ Red List status will align with the Green Status, but other times the two metrics will not match up. Take the burrowing bettong (Bettongia lesueur), a small marsupial, for example. The species’ Red List status is “near threatened,” which suggests that while the species is in peril there isn’t an immediate risk of extinction. But the Green Status shows that the burrowing bettong is actually “critically depleted” from its range and does not have a high recovery potential due to the difficulties in controlling invasive species like cats and foxes that prey upon these animals.

Less than 2% of the surveyed species had a conservation impact metric of zero, which indicates “that conservation has, or will, play a role in improving or maintaining species status for the vast majority of these species,” the authors write in the paper.

Co-author Elizabeth Bennett, vice president for species conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), says the new framework can help incentivize conservation action.

“There are… donors that are starting to be interested in this because it’s more fine-tuned and sensitive to change than the Red List,” Bennett told Mongabay. “So within a granting period, you potentially could improve the green status of a species, where the Red List status tends to be much slower to react to change.”

Burrowing bettong (Bettongia lesueur), a near threatened species that is critically depleted from its native range in Australia. Daniele Parra / Flickr

The IUCN Green Status will be officially launched online at the start of the IUCN World Conservation Congress, which will take place in Marseille, France, from Sept. 3-11, 2021.

“The core thing that excites me is that it’s an optimistic view of where we want to go with species conservation,” Bennett told Mongabay. “And it gives people a really good clear roadmap about that for each species. So instead of just saying, Oh, we don’t want this species to go extinct… we can say, but we want it to be thriving, and we want to be playing its full ecological role. And this is what it could look like. And this is how we can get there.”

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

- Giant Pandas No Longer Endangered Thanks to Conservation ...

- Red Kites Are Thriving in UK Thanks to Conservation Effort - EcoWatch

- Fireflies Face Extinction From Habitat Loss, Light Pollution and ...

- Will Climate Change Drive the Komodo Dragon to Extinction?

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe