From Australia’s Great Barrier Reef to the Caribbean, the climate crisis is already having a profound and deadly impact on the world’s coral reefs. But how will this affect each of the different ecosystems and communities that rely on coral’s unique ability to construct habitats and protect coastlines?

A research team based at the University of São Paulo in Brazil has helped answer that question for the tropical Atlantic by assessing how the range of three key species of corals will shift depending on how many more greenhouse gases are pumped into the atmosphere.

“Our most striking result was that all three species that we selected and that are important reef-builders of the Atlantic will face changes in its distribution, regardless of the scenario,” study lead author and Ph.D. candidate Silas Principe told EcoWatch in an email. “That is, even if we are able to reduce the emissions and climate change, we will still see changes in the coral reefs of the Atlantic.”

Reef Builders

The research, published in Frontiers in Marine Science Monday, focused on three species of stony corals that are important for the construction of Atlantic tropical reefs: Mussismilia hispida, Montastraea cavernosa and the Siderastrea complex. These species act as “ecosystem engineers,” a Frontiers press release explained, playing a similar role in the marine environment to the role beavers and their dams play on land.

“Even when not playing a major role as a builder, all these species contribute to increase the complexity — the 3D structure — of the reefs, which creates spaces and resources for other species,” Principe said.

That means that, if these species leave a particular area, their absence will have a profound impact on the entire reef. This, in turn, could impact human communities that rely on reefs for “ecosystem services” such as coastal protection, tourism and food.

Range Change

To find out how the three species’ ranges might shift as global temperatures warm, the researchers first looked up the species’ current distribution in databases like the Global Biodiversity Facility and the Ocean Biodiversity Information System. They then connected this distribution to the species’ ideal conditions, such as sea surface temperature. Using models, they were then able to predict what the corals’ range would be by 2100 based on low, moderate and high predictions for greenhouse gas emissions.

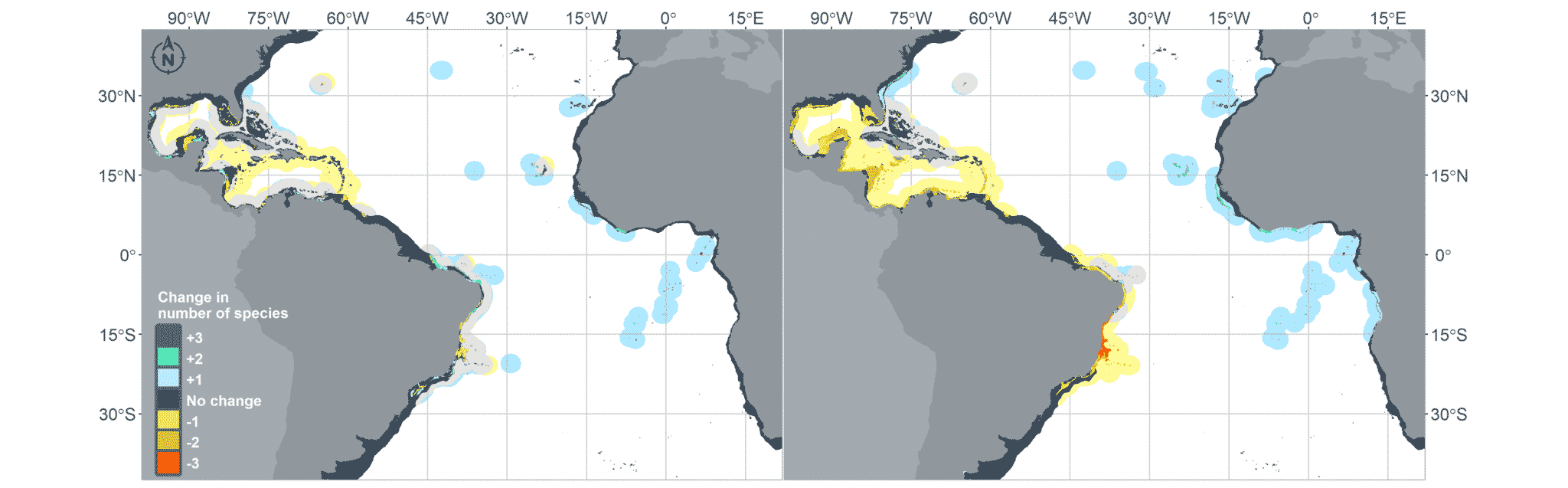

They found that the range of all three species would change under all potential emissions scenarios and all species would lose habitat by 2100 under the worst case scenario. M. Hispida was especially at risk, as it was projected to lose habitat in every emissions scenario. The study authors prepared a website that allows users to see in detail how each coral’s range will change under which emissions scenario.

The study also predicted that some Atlantic regions would be more impacted than others. In particular, Brazilian reefs are vulnerable because they are constructed of fewer species.

“Here, the loss of the endemic Mussismilia hispida and of the Montastraea cavernosa could cause major changes in the coral reefs,” Principe said.

This would especially be a problem for the traditional communities of Brazil’s Abrolhos region, who rely on the fisheries of the reefs for food.

Other areas projected to lose important species were parts of the western Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, study coauthor and Principe’s supervisor Dr. Tito Lotufo told EcoWatch in an email.

Climate change could also open up new potential habitats for the coral species as conditions change, especially in the Eastern Atlantic, including the coast of Africa. However, Principe noted that there are several uncertainties surrounding range expansion.

For one thing, there is no guarantee that a species will be able to establish itself in a new area, even if the conditions seem right. Further, if a species does migrate, there is no guarantee that it will thrive in its new home.

There is also no guarantee that the new corals would actually benefit their new environments.

“Some places in the world are already facing something called ‘tropicalization,’ with tropical species invading temperate marine ecosystems and producing major changes,” Principe said.

Changes in the number of coral species predicted for the lowest-emission (RCP 2.6; left panel) and highest-emission scenario (RCP 8.5; right panel). Yellow shaded areas highlight the regions where the loss of species is predicted, blue areas where the number of species may increase.Silas C. Principe, André L. Acosta, João E. Andrade, Tito M. C. Lotufo

Facing the Future

That said, the study does provide some insights that could help with coral conservation. It identified some areas in which the corals’ range was projected to remain constant. These would make ideal coral havens.

“Policy makers should have a more careful look into these places where no changes are predicted and that may constitute safe-areas for coral reefs, demanding conservation actions,” Principe advised.

The team plans to continue their research by conducting similar range studies for other important reef species, such as algae and fish, to have a fuller understanding of how climate change will impact coral reefs in the tropical Atlantic.

For now, however, they emphasized that their research, and the plight of coral generally, is an urgent argument in favor of climate action and adaptation.

“For many years now we have already witnessed important changes in most coral reefs around the world, with massive bleaching and clear changes in the reefs’ seascapes,” Lotufo said. “Hence, they are not only threatened, but already strongly impacted by climate changes, especially global warming resulting from human CO2 emissions… We need now not only to urgently reduce these emissions, but also plan ahead and put together a strategy to cope with the projected consequences.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe