Individual standing in Hurricane Harvey flooding and damage. Jill Carlson / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

By Allegra Kirkland, Jeremy Deaton, Molly Taft, Mina Lee and Josh Landis

Climate change is already here. It’s not something that can simply be ignored by cable news or dismissed by sitting U.S. senators in a Twitter joke. Nor is it a fantastical scenario like The Day After Tomorrow or 2012 that starts with a single crack in the Arctic ice shelf or earthquake tearing through Los Angeles, and results, a few weeks or years later, in the end of life on Earth as we know it.

Instead, we are seeing its creeping effects now — with hurricanes like Maria and Harvey that caused hundreds of deaths and billions of dollars in economic damage; with the Mississippi River and its tributaries overflowing their banks this spring, leaving huge swaths of the Midwestern plains under water. Climate change is, at this very moment, taking a real toll on wildlife, ecosystems, economies, and human beings, particularly in the global south, which experts expect will be hit first and hardest. We know from the increasingly apocalyptic warnings being issued by the United Nations that it will only get worse.

But these early omens of our unstable, hot, wet future can be difficult to wrap our heads around. So Teen Vogue partnered with the team at the nonprofit news service Nexus Media, who developed a timeline predicting how climate change could affect three major U.S. cities over the course of the 21st century. Climate change will look different in different places across the world, but we chose three places with distinct geographic concerns and climate vulnerabilities — to ground all the ominous statistics and headlines in a real sense of place. These are cities you may have visited, or where you may have family, or where you may even live.

According to the research Nexus compiled, St. Louis will see flooding, extreme heat, severe rainfall, and drought in the surrounding farmland. In Houston, on the Gulf of Mexico, hurricanes will grow more destructive and temperatures will soar. San Francisco will witness rising sea levels, fierce wildfires, and extreme drought.

This timeline is based on interviews with a dozen climate experts and a review of several dozen scientific studies. The projections assume an average sea level rise of six feet by 2100 — a little more in some places, and less in others — and the business-as-usual emissions scenario, which assumes that we will continue to pollute and use fossil fuels at our current rate.

Rather than a scientific assessment, it is a rigorously researched prediction of what our future could bring unless we come together as a country and as a global community — fast— to address climate change as the crisis it is.

As Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University, put it: “The future is not set in stone. Some amount of change is inevitable. It’s as if we’ve been smoking a pack of cigarettes a day for decades, but we don’t have lung cancer yet.”

“The amount of change that we’re going to see — whether it’s serious, whether it’s dangerous, whether it’s devastating, whether it’s civilization-threatening — the amount of change we’re going to see is up to us,” she continued. “It depends on our choices today and in the next few years.”

2020

Houston

It’s starting to get hot. It’s now about one degree Fahrenheit warmer in Houston than it was in the second half of the 20th century. Houstonians can expect especially balmy falls this decade, as autumns are warming faster than other seasons in Texas.

Houston knows how much it stands to lose from climate change. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey devastated the city, which was supercharged by warm waters in the Gulf. But Houston is also helping to drive the rise in temperature. Several major oil companies and a vast network of oil refineries and petrochemical plants call the city home.

St. Louis

This decade, St. Louis is expected to be more than two degrees Fahrenheit warmer than it was, on average, during the latter half of the 20th century. While locals have endured more sweltering summer days, they have felt the change the most during the cold months. Missouri winters are warming faster than summers, springs, and falls.

Warmer air holds more water, which can lead to more severe rainfall. In recent years, rainstorms have pummeled the Midwest and led to widespread flooding across the region. In 2019 in St. Louis, rivers reached near-historic levels, and floodwaters inundated the area around the city’s iconic Gateway Arch.

This storm wasn’t a blip on the radar, but rather a sign of what’s to come. As the planet heats up, St. Louis can expect more extreme rainstorms — and more orders to evacuate low-lying neighborhoods.

San Francisco

For San Franciscans, the beginning of the decade will feel only a little different from past years. In 2020, it’s expected to be less than one degree Fahrenheit warmer in San Francisco than it was, on average, between 1950 and 2000. The change is small, but locals can sometimes feel it in the spring, which is warming faster than the other seasons, or on especially hot days.

But there are new worries for the city. Rising temperatures have fueled ongoing drought in recent years, which has, in turn, led to more wildfires. Fires now burn more regularly across the Sierra Nevada as well as coastal mountain ranges. The flames may ruin plans for weekend getaways to Yosemite or deliver noxious smoke to the Bay Area. And locals may start to reach for air masks as dangerously smoky days become more common.

“We get a lot of the smoke that comes from the wildfires that happen in inland California, and that makes it really hard to breathe the air,” said Kristy Dahl, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, who is based in San Francisco. “Last year when there was a massive wildfire hundreds of miles away, San Francisco for a day [ranked among] the worst air quality in the entire world.”

2030

NEXUS MEDIA

Houston

By 2030, temperatures are expected to have warmed almost two degrees Fahrenheit in Houston. Seas are expected to have risen a little more than a foot, enough to occasionally flood some low-lying areas outside the city. Warmer waters in the Gulf of Mexico will raise the speed limit for winds during hurricanes and ramp up rainfall during storms.

“Hurricanes are not getting more frequent, but they are getting stronger and bigger and slower,” said Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University. “They’re intensifying faster and they have a lot more rain associated with them today than they would have had a hundred years ago.”

St. Louis

By 2030, temperatures are expected to have warmed around three degrees Fahrenheit in St. Louis. The kind of rainstorm that currently strikes the Midwest around once every five years will hit around once every three years this decade.

“We’ve seen these record-breaking, devastating floods in the Midwest,” said Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University. “It’s not like they’ve never had floods before, but the floods are just getting a lot worse and a lot more frequent.”

This could mean trouble for local infrastructure. Rivers swell after heavy rains, and the rush of water can weaken bridges by carrying away sediment from around their foundations. This could be a big problem in Missouri, which is home to hundreds of aging bridges, many of which have been deemed deficient. Climate change could mean even more heavy repair costs for taxpayers.

San Francisco

This decade, the rise in temperature is expected to pass two degrees Fahrenheit in San Francisco. That may not feel like a lot in the city. But warmer weather is taking a serious toll.

California’s drought will get progressively worse this decade, the product of warmer temperatures drying out soil and meager rainfall failing to replace the water lost. Rising temperatures will also yield less snowfall. The snow that does come down will melt in the spring and early summer, depriving the state of a critical source of water in the late summer, when, historically, melting snow has fed streams and rivers.

The snow drought will strain farmers in the Central Valley, while putting pressure on cities to use less water. The water restrictions the state put in place in 2018 will have grown much more severe in the past 12 years. Officials could urge Californians across the state to take shorter showers and stop watering their lawns to cope with the worsening drought.

2040

Houston

This decade, sea level rise around Houston is projected to reach two feet, enough to inundate much of nearby Freeport and Jamaica Beach. That extra water will mean that hurricanes, when they strike, will deliver more powerful floods to coastal areas.

“A small and steady rise of the water level elevates a platform for flooding that we’ve had throughout history,” said Maya Buchanan, a sea level rise scientist at Climate Central. “That means larger storm surges.”

That’s bad news for people who live near the shore. Around half of deaths caused by hurricanes are the result of coastal flooding, and waters tend to inundate poor neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color, which are more likely to lie in flood-prone areas.

St. Louis

In 2040, St. Louis is expected to be four degrees Fahrenheit warmer than it was at the end of the last century. While that may sound like a small number, it means big problems for the city. A small uptick in the average temperature could lead to milder winters, stifling summers and changing rainfall.

St. Louis will tend to see wetter springs and drier summers. That means the region will withstand heavier downpours, but it will also endure long stretches without a drop of rain. Despite the growing peril of major flooding, extended dry spells and rising temperatures will dry out the land. Drought will set in in Missouri, endangering farms.

And just remember — it will never be this cool again.

San Francisco

By 2040, sea levels are predicted to rise around one foot, enough to encroach the beaches on the west side of the city and Candlestick Point on the east, popular recreation areas. Parts of San Francisco Airport and Oakland Airport will flood regularly, making air travel in and out of the city more difficult.

Drought will have grown increasingly severe. Forests will dry out, and become vulnerable to bark beetles, which burrow into trees to lay their eggs. Healthy trees can ward off the bugs by covering them in resin — but already struggling trees have no way to protect themselves.

Large parts of forests will die, and the dead trees will become tinder for wildfire. In 2040, fires are expected to burn around twice as much big sections of the Sierra Nevada as they do today. Areas south of San Francisco will also grow more vulnerable to erupting in flames.

2050

Houston

By midcentury, temperatures are expected to have warmed more than three degrees Fahrenheit in Houston. Waters in the Gulf of Mexico will have also warmed, fueling more dangerous storms.

In the decades to come, the Gulf will see more category-four and -five hurricanes, like Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Katrina, according to Suzana Camargo, a climate scientist at Columbia University. Warm water is like ammunition for cyclones, arming them with more powerful winds and heavier rains. People might want to think twice before they purchase a home in Houston.

“I think people have to think very carefully how they are going to plan when they want to buy a house,” Camargo said, explaining that in the future, cyclones will deliver more flooding to seaside cities and towns.

St. Louis

St. Louis is expected to have heated up by more than five degrees Fahrenheit on average by the middle of the century. Hot weather will dry out soil. Past 2050, the Central Plains, including much of Missouri, can look forward to decades-long drought.

This drought will be especially disastrous for Missouri farmers. Growers will have to take more water out of underground aquifers to feed their crops, drawing down a limited supply of groundwater, often at great cost. This, in turn, could drive up the price of food.

San Francisco

By 2050, temperatures in San Francisco are expected to have risen more than three degrees Fahrenheit. In the second half of this century, changing weather patterns will yield lasting dry spells, leaving much of California to endure long stretches without rain. Around the time someone graduating high school today turns 50, they can expect California to enter a decades-long drought — with disastrous consequences.

Farmers in California will have to draw more and more water from underground. Eventually, they may not be able to grow fruits and vegetables in parts of the state. This will drive up the cost of many foods, such as strawberries, almonds, and lemons.

Snow will also start to disappear from the Sierra Nevada. By 2050, projections say, there will be a third less snow than we see today. San Francisco depends on that snow for its water, and a dry Sierra Nevada could mean a looming water crisis for the city.

The drought will also leave California’s forests all the more vulnerable to wildfire — fires that could cover San Francisco in smoke, making it dangerous to go outside.

2060

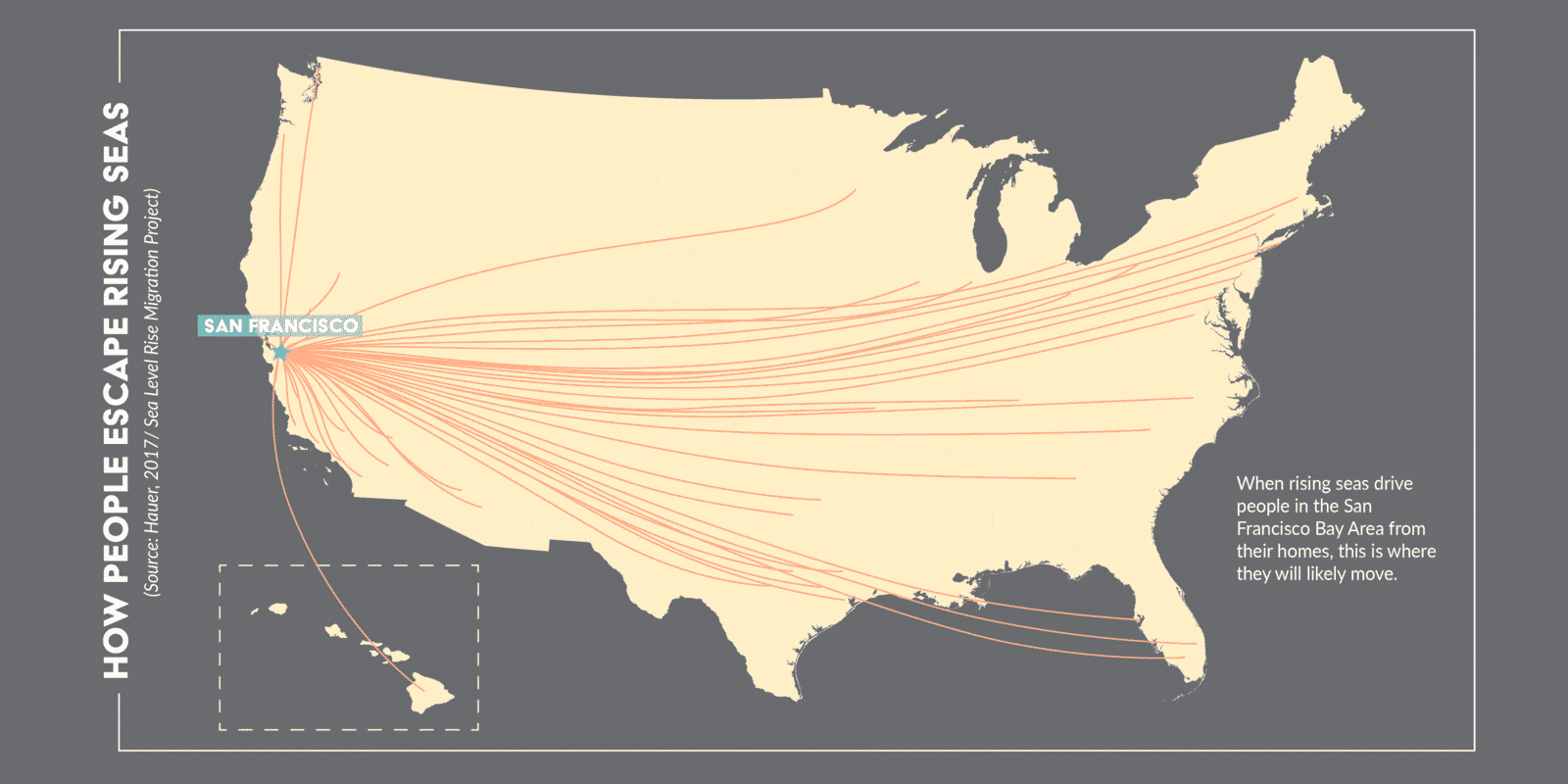

Where San Francisco residents are expected to move when they’re displaced by rising seas..

NEXUS MEDIA

Houston

By 2060, temperatures are expected to have warmed by more than four degrees Fahrenheit. The city could see up to 25 days a year with temperatures over 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Local sea level rise, meanwhile, is expected reach three feet during this decade. This will raise the level of Buffalo Bayou, the waterway that stretches through the middle of Houston. The Scholes International Airport in nearby Galveston will sink into the sea, and at high tide, water will flood much of the San Jacinto Battleground, site of the 1836 clash where Sam Houston, the city’s namesake, overcame the Mexican Army.

St. Louis

St. Louis is expected hit a six-degrees-Fahrenheit increase in its average temperature this decade. While this might be bad news for humans, it’s good for many insects, who love warm weather. Rising temperatures will bring disease-carrying mosquitoes to St. Louis’s doorstep. Missourians will have to be more vigilant about their health as the bugs could spread tropical viruses like Zika, dengue, and yellow fever around the warming Midwest.

Climate change will also bring more deer ticks to St. Louis. Because warmer air can hold more water, as temperatures rise, so does humidity — and deer ticks thrive in humid weather. While ticks are little seen in Missouri today, later this century they will fan out across the state, potentially spreading Lyme disease. Those afflicted will endure fever, headache, and fatigue. They may see their joints swell or feel their face droop.

San Francisco

By 2060, temperatures in San Francisco are expected to have risen by more than four degrees Fahrenheit.

Wildfires will burn roughly three times as much of broad swaths of the Sierra Nevada as they do today, laying waste to large stretches of California’s pristine forests.

This decade, sea level rise is projected hit two feet. Water will begin to spill over the edges of the Mission Creek Channel, while threatening routine floods around San Francisco’s iconic Fisherman’s Wharf. Waters will have flooded much of nearby San Rafael, north of San Francisco. To the south, Foster City will be underwater, displacing thousands of residents — many of whom currently work in the tech industry.

2070

Houston

By 2070, Houston is projected to be more than five degrees Fahrenheit hotter than at the end of the 20th century. This warming is part of a larger trend that is heating up the planet and melting ice in Greenland and Antarctica, raising the sea level near the city.

“As flooding events get more severe, that can impact property values, and that could impact where people decide to live,” Buchanan said, explaining that rising seas will drive down the value of homes in low-lying areas.

By this time, waters will have already subsumed much of the coastline from Freeport, south of Houston, all the way to New Orleans. Rising seas will make much of the Gulf coast unrecognizable as the ocean swallows up most of southern Louisiana. Later this decade, sea levels are expected to have risen by four feet.

St. Louis

In 2070, St. Louis is projected to be more than seven degrees Fahrenheit hotter than it was at the end of the last century. Before the decade is through, the city is expected to see eight degrees Fahrenheit of warming. Rising temperatures will have utterly transformed the weather in Missouri, making it virtually unrecognizable to current residents. The city will see around 20 fewer days of frost each year than it does today, as well as around 20 extra days with temperatures over 95 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat will be felt most acutely in neighborhoods short on trees and parks.

Outside the city, severe heat will cripple the growth of corn and soybeans at nearby farms. So will drought, which experts say will be worse than at any time in living memory. The state will endure more consecutive days without rain. When it does rain, however, it will pour. Warmer temperatures will produce more extreme rainfall.

San Francisco

By 2070, San Francisco’s average temperature is expected to have warmed by more than five degrees Fahrenheit. Drought will be more severe than at any time in living memory. Rising temperatures and diminished rainfall will take a toll on trees around the San Francisco Bay. More and more evergreen forests will die off and grasslands will spring up in their place, fundamentally changing the landscape around the city.

2080

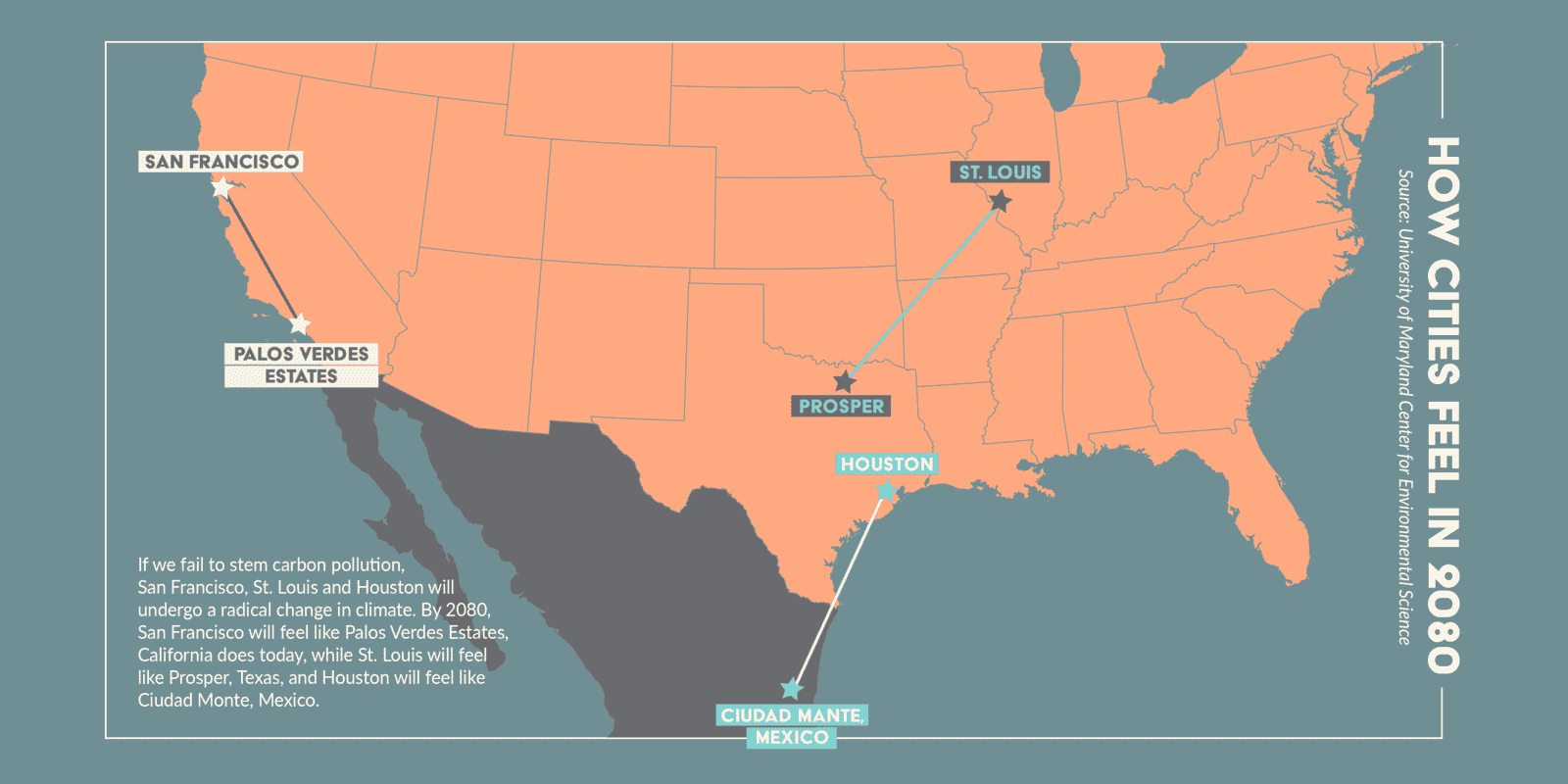

This is what Houston, St. Louis, and San Francisco will feel like in 2080.

NEXUS MEDIA

Houston

By 2080, temperatures are projected to have warmed around six degrees Fahrenheit on average, a dizzying change in the weather that means Houston won’t feel like Houston anymore.

The city will grow warmer and wetter. Around 2080, Houston will feel something like Ciudad Mante in Mexico does today, with its warmer, drier winter.

As the climate changes, Houston’s native wildlife could start to head north. At the same time, plants and animals that currently make their home south of Houston may start to work their way toward the city.

St. Louis

St. Louis is expected to be nearly nine degrees Fahrenheit warmer by 2080. The temperature will have changed so drastically that St. Louis no longer feels like the same city.

Around 2080, St. Louis will start to feel like Prosper, Texas, does today. This new St. Louis will be hotter and drier. Summer weather will go from balmy to sweltering, and the city will see much less rain during the warm months.

It’s not just that St. Louis will feel more like Prosper. It might start to look like it too. Animals that currently live around Prosper could head northward as the climate changes, searching for a new home that feels like their old one. At the same time, the shrubs and grasslands that stretch across north Texas could start to edge their way toward Missouri.

San Francisco

By 2080, the average temperature is expected to have risen by more than six degrees Fahrenheit in San Francisco. The city will start to feel a lot like present-day Los Angeles. The weather will be warmer and drier, much like the current climate in Palos Verdes Estates, a coastal city in the L.A. area.

With less rainfall, many of the trees that make their home in San Francisco will die. At the same time, the smaller, scrubbier plants that make their home in L.A. could migrate toward the city. It’s not just that San Francisco will start to feel like L.A., scientists say. It might start to look like it too.

2090

Houston

By now, temperatures are projected to have warmed close to seven degrees Fahrenheit, while sea levels will have risen five feet, subsuming the coastline. Much of nearby Galveston is underwater.

It’s not just hot days that threaten Houston. Rising temperatures will allow the air to hold more water, increasing humidity — which could be a big problem for public health.

“As humidity rises, it becomes harder and harder for the sweat to evaporate off our skin — and it’s that evaporation of sweat that cools our bodies,” said Kristy Dahl, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “So it might only be a temperature reading of 90 degrees, but if you have 60% humidity, it’s going to feel hotter than 90 degrees.”

Dahl said that Houston will heat up so much that it will be hard to quantify how hot it will feel.

“By the end of the century, Houston would see about three weeks of what we call off-the-charts heat conditions, which are when the combination of temperature and humidity falls above the national weather services heat index scale,” she said. “What that means is that we can’t even calculate a heat index to reliably warn people about how dangerous it is.”

St. Louis

St. Louis is expected to have warmed by almost 10 degrees Fahrenheit, a transformational change in the climate of the city. Rising temperatures could provoke a spike in violent crime — when people are hot, research shows, they tend to feel more aggressive.

By the end of the century, St. Louis will endure around 80 days per year where the heat index is above 100 degrees — compared to just 11 days at the end of the 20th century, according to Kristy Dahl, a climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“It’s really striking because historically those off-the-charts conditions have only occurred in the Sonoran desert region of the U.S., the California-Arizona border,” Dahl said.

In addition to extreme heat, the city will also endure severe drought, punctuated by the occasional supercharged rainstorm. The kind of downpour that currently strikes the Midwest around once every five years will hit around once every year or two. The most severe storms — the kind that currently show up once every 20 years — now arrive once every six or seven years.

Heavy rainfall will lead to flooding, and floodwaters will mix with raw sewage, helping to spread bacteria. Rains will also swamp homes and businesses, offering a place for mold to grow.

San Francisco

By now, San Francisco is projected to have heated up more than seven degrees Fahrenheit on average. The extra heat will mean many people will be spending more time outdoors, potentially leading to a spike in violent crime.

The state will be mired in lasting drought. Wildfires could consume around four times as much of huge sections of the Sierra Nevada as they do today, as well as forests closer to San Francisco, endangering locals.

The Bay Area is expected to have seen more than three feet of sea level rise. The San Francisco and Oakland Airports will be completely underwater. Across the bay, coastal flooding will inundate parts of Alameda. Low-lying areas on the south end of the San Francisco Bay will also be flooded, including some of San Jose.

2010

NEXUS MEDIA

Houston

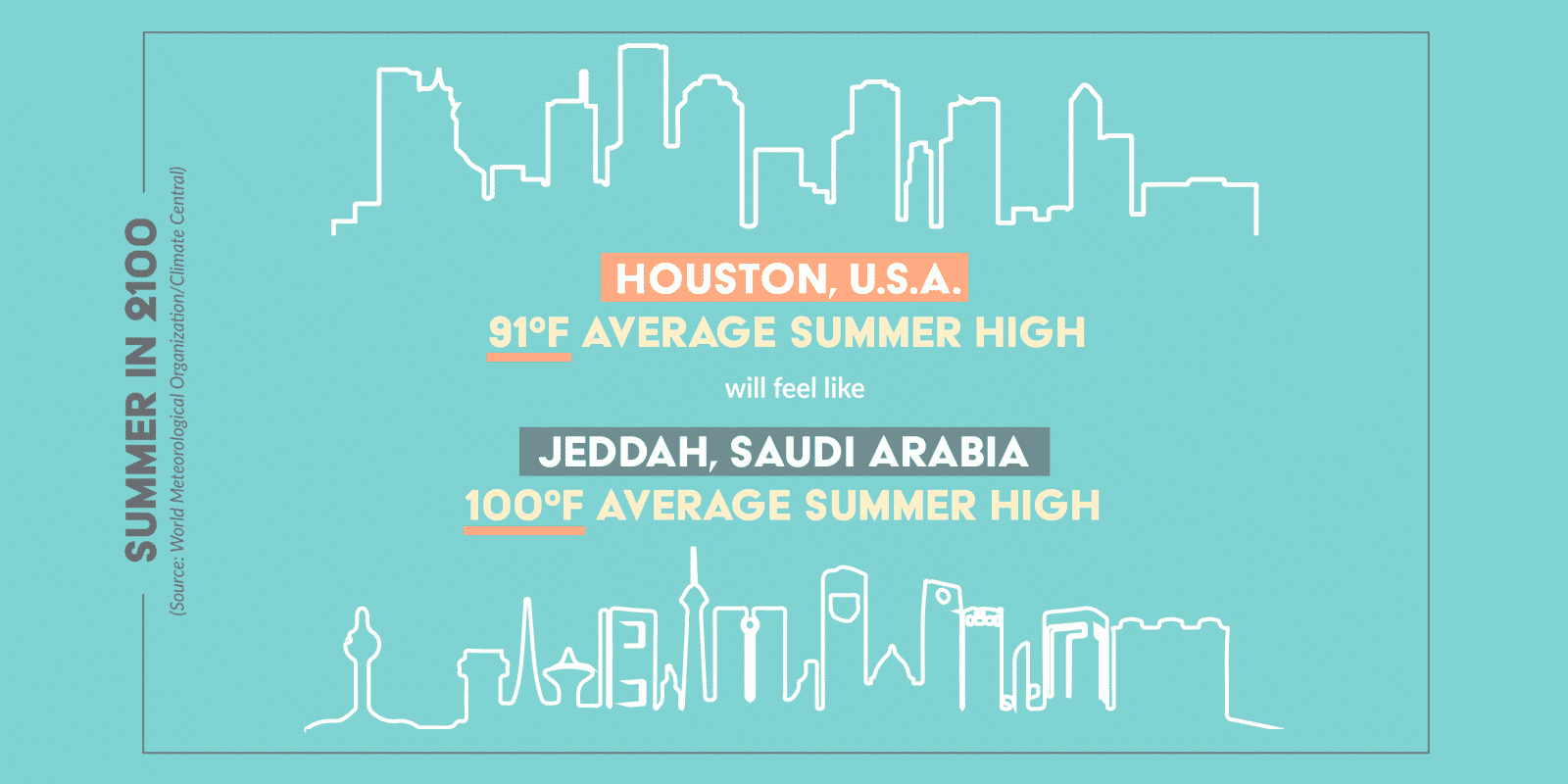

By the end of this century, temperatures are expected to have warmed close to eight degrees Fahrenheit in Houston. In the summer, Houston will feel something like Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, does today. High temperatures will average over 100 degrees Fahrenheit during the warmest months.

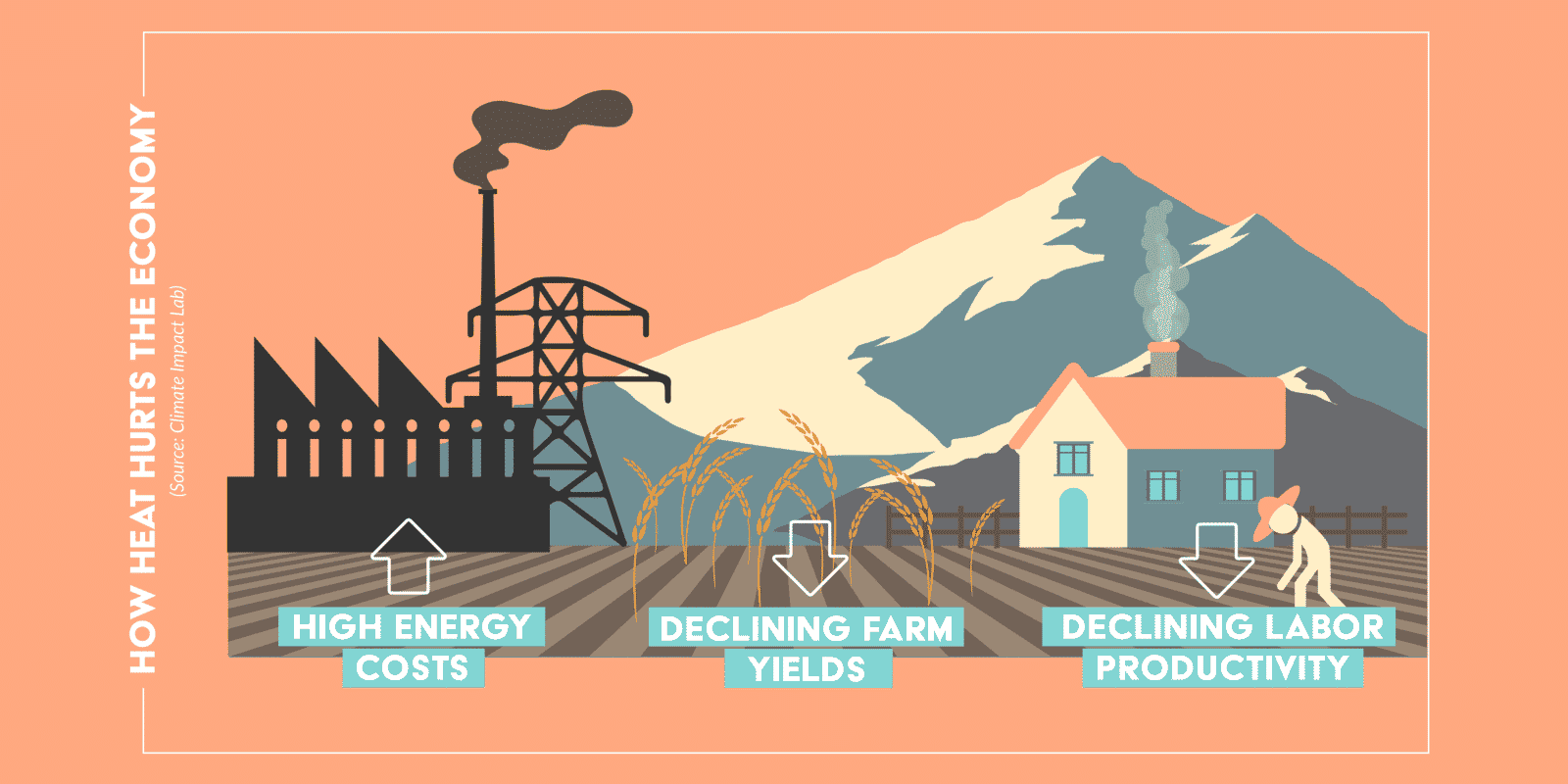

By making life harder for workers, severe hotter weather will shrink the economy of the greater Houston area by 6%. Extreme heat will also kill hundreds more people each year. Poorer neighborhoods tend to be warmer, in part because they tend to have fewer trees. People who live in those neighborhoods are also less likely to have air conditioners, which will put them at greater risk.

On top of the heat, Houston is expected to have seen close to six feet of sea level rise by 2100. Waters encroach on the east side of town near the water, where oil refineries and chemical plants could continue to service our catastrophic addiction to oil and gas. Routine flooding of these facilities may cause dangerous explosions and potentially release toxic chemicals into the air.

Much of the city, however, will stay safe from the encroaching sea. That means the Houston could absorb hundreds of thousands of new residents by 2100 — people who were driven from Miami and New Orleans by ever-worsening coastal floods.

St. Louis

By the end of this century, St. Louis is expected to have warmed by roughly 11 degrees Fahrenheit. Winter will scarcely look like winter. Summers will have gone from hot to unbearable.

During the hottest months, it will be so scorching that it will be dangerous to go outside for much of the day. People will depend more on air conditioners to stay cool, leading to bigger electric bills. Elderly people, particularly those who can’t afford to run an air conditioner, will face the risk of heat stroke and death.

The intense heat will take an immense toll on the local economy. Farms in Missouri and southern Illinois could see yields cut in half, ruining livelihoods.

In St. Louis itself, experts project that heat will stifle productivity by making it too hot to work. This could help cut the city’s economic output by around 8%.

San Francisco

By 2100, San Francisco is expected to have heated up by more than eight degrees Fahrenheit on average. It will be hot and dry. Snow will be hard to find in the Sierra Nevada. By 2100, the mountain range will see two thirds less snow than we see today, depriving San Francisco of a much-needed water source.

Seas will have risen four feet, projections say. Large parts of Alameda will be underwater. Hunters Point will have flooded, as well as much of Mission Bay. And flooding won’t be limited to San Francisco.

Sea level rise could flood the homes of 13 million Americans by the end of the century, leading to a massive exodus from many coastal areas. By one estimate, rising seas in places like Oakland, Alameda, and San Mateo could spur close to 300,000 residents to move to inland cities in Arizona, Texas, and New Jersey. It is the poorest neighborhoods that will be the most vulnerable to floods.

Note: This story is based on RCP 8.5, the so-called “business-as-usual” emissions scenario that assumes that Earth will continue to heavily rely on fossil fuels as the global economy grows. Per Nexus Media, “As we are currently doing virtually nothing to stop climate change, RCP 8.5 is a pretty good predictor of what’s going to happen over the next couple of decades. Part of that is because it will take a while for the climate to reach a new equilibrium, so even if we stopped polluting now, the planet would continue to warm for decades.” It looks at a sea level rise of six feet, on average, globally, based on the findings of this widely-cited 2014 study.

This story originally appeared in Teen Vogue in partnership with Nexus Media. It is republished here as part of EcoWatch’s partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

- 8 World Cities That Could Be Underwater as Oceans Rise - EcoWatch

- Will the U.S. Be a Dystopian Hellscape in 2100 if Emissions Keep ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe