Phages: Bacterial Eaters From Georgia to Fight Antibiotic Resistance

By Tim Ruben Weimer

Tanja Diederen lives near Maastricht in the Netherlands. She has been suffering from Hidradenitis suppurativa for 30 years. Its a chronic skin disease in which the hair roots are inflamed under pain — often around the armpits and on the chest.

€3,900 ($4,302) for treatment in Georgia

In August 2019, the now 50-year-old made a radical decision: she discontinued the antibiotics, which were becoming less and less effective. And she traveled to Georgia for two weeks to undergo treatment with bacteriophages (or phages for short).

Such phage therapy is not yet approved in most Western European countries. She paid 3,900 euros out of her own pocket in the hope that the unconventional therapy would help her.

Bacteriophages are viruses that fight against the proliferation of their host bacteria. Therapy with bacteriophages involves the oral administration of a single, isolated type of phage. They attach themselves to their bacterial counterparts in the patient’s body in order to survive.

The phages reverse the polarity of the bacterial cell in such a way that it produces further phages, filling up with more and more phages and finally bursts. Then, the released phages attach themselves to other bacteria until all of the bacteria has been destroyed.

Journey Into the Unknown

“It tastes a bit like mushrooms,” Tanja Diederen remarked as she took her morning phage dose. “When I went to Georgia, I was at first very nervous and excited, but above all disappointed about the treatment here in Holland.”

After antibiotics stopped working for her, her doctor suggested that she take biopharmaceuticals, i.e. genetically engineered drugs. He had never heard of bacteriophages.

Instead, Diederen decided to look for treatment options with bacteriophages on her own, which she had heard about in a television program.

The Doctor Never Heard of Phages

A phage model — phages are viruses, that multiply in bacteria and then destroy them.

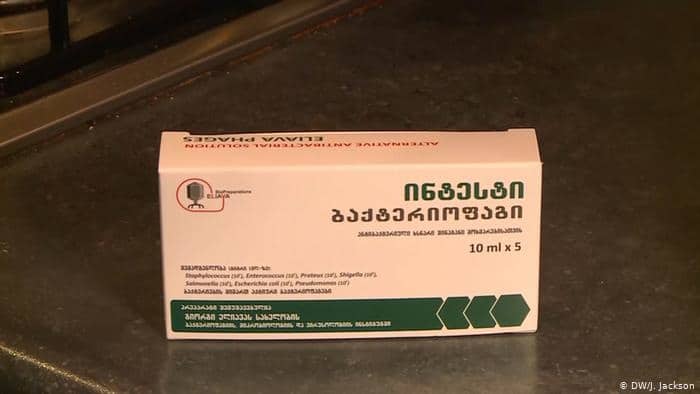

She came across the Georgi-Eliava Institute in Georgia, which has been researching bacteriophages since 1923 — just a few years after their discovery. Georgia has since developed into the global center of phage therapy.

During the Cold War, antibiotics were difficult to get there or anywhere in the Soviet Union. Treatment with phages was the best way to cure infectious diseases. Today, the Eliava Institute has one of the largest therapeutic collections of bacteriophages in the world.

Tanja Diederen stayed in treatment for two weeks, after which she traveled back to the Netherlands with a large suitcase full of phage tins. Since she began taking two different phages a day and applying a cream, she feels better.

She has more energy again and the small inflammations on her chest and armpits have decreased. The large inflammations come and go, but not as severe as before.

“It Doesn’t Feel Illegal to Me”

Communicating with the Georgian doctors was difficult for Tanja Diederen. She needed a translator.

Every three months Diederen travels to Belgium — 15 kilometers away — to pick up a new ration of bacteriophages sent from Georgia for 500 euros. Her health insurance doesn’t pay for this. Belgium is the only Western European country where phages are allowed. In the Netherlands, as in all other countries, they can only be used in individual cases to save lives or relieve severe pain.

Her physician is solely responsible for the application.

“It doesn’t feel illegal to me,” said Diederen. “I am one hundred percent sure that this medicine will help many people.”

Like antibiotics, bacteriophages can also lead to bacterial resistance. Their big advantage, however, is that they are always one step ahead of the bacteria and can overcome the resistance. In addition, they are always directed against a specific type of bacteria and thus leave useful bacteria undamaged, like in the intestine, for example.

Before phage treatment, it is always necessary to determine which bacteria actually trigger the disease. The phages are then produced individually for each patient — often in Georgia.

Bacteriophages Permitted in Belgium

Professor Jean-Paul Pirnay from the Queen-Astrid Military Hospital in Brussels works with bacteriophages.

Such an individual medication does not meet the applicable regulations for medicinal products in any Western European country. It would take too much effort to have each individual phage formulation approved by the authorities.

Not so in Belgium. Since last year, this process can be legally circumvented by the Scientific Health Institute, in cooperation with doctors, patients, manufacturers, pharmacists and the Belgian Federal Office for Medicinal Products, issuing a certificate for the required phage ingredients. Pharmacists will then be able to use them for the manufacture of bacteriophages, subject to certain guidelines.

“We have used the existing legal framework to insert the bacteriophages,” said Dr Jean-Paul Pirnay, who works at the Queen Astrid Military Hospital in Brussels on bacteriophages.

Around 30 patients have already been treated there. Currently, the military hospital is the only place in Belgium where bacteriophages are produced.

Useful Supplement to Antibiotics

“We need pharmaceutical companies to make the phage,” says Pirnay. “A hospital can’t produce all phages for a growing number of patients.”

But industrial production of phages would require a clearer legal framework, and research is not yet ready.

“I believe that phages will not replace antibiotics,” he said. “Both will be used together to make antibiotics more effective.”

Tanja Diederen wants to continue her treatment in Brussels in the future. Communication with the Georgian doctors was difficult for her, she always needed a translator.

“I really hope that phages will soon be allowed in Europe,” she said. “Going to Georgia is quite difficult and expensive.”

Germany and the Netherlands are currently conducting pilot studies to see whether an individual prescription of bacteriophages would be possible. France has already imported Belgian phages and agreed to their use.

Reposted with permission from Deutsche Welle.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe