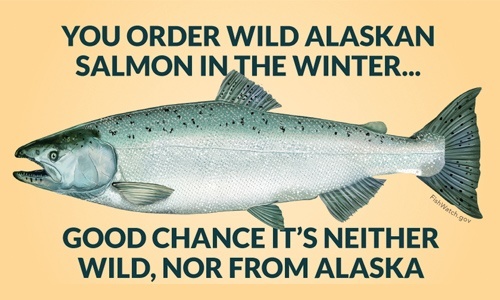

That wild Alaskan salmon you get at your favorite local restaurant might not be the real deal, according to a new report from the nonprofit Oceana. The report reveals that America’s favorite fish—salmon—is often mislabeled in restaurants and grocery stores.

.@Oceana study finds mislabeling in 43% of salmon samples tested https://t.co/BFrM18Cacy #SeafoodFraud pic.twitter.com/YukAdNkiuI

— Oceana (@oceana) October 28, 2015

The nonprofit collected 82 salmon samples from restaurants and grocery stores between December 2013 and March 2014 and found that 43 percent were mislabeled. DNA testing confirmed that the majority of the mislabeling (69 percent) consisted of farmed Atlantic salmon being sold as a wild-caught product.

“Americans might love salmon, but as our study reveals, they may be falling victim to a bait and switch,” said Beth Lowell, senior campaign director at Oceana. “When consumers opt for wild-caught U.S. salmon, they don’t expect to get a farmed or lower-value product of questionable origins. This type of seafood fraud can have serious ecological and economic consequences. Not only are consumers getting ripped off, but responsible U.S. fishermen are being cheated when fraudulent products lower the price for their hard-won catch.”

Oceana found salmon was mislabeled in nearly half of samples taken in Virginia (Virginia Beach, Norfolk, Newport News, Williamsburg, Richmond and Fredericksburg) and Washington, DC. Nearly 40 percent of samples were mislabeled in Chicago and New York City. Mislabeled, according to Oceana, meant “1) they were described as being ‘wild,’ ‘Alaskan’ or ‘Pacific,’ but DNA testing revealed them to be farmed Atlantic salmon; or 2) the samples were labeled as a specific type of salmon, like ‘Chinook,’ but testing revealed them to be different species (in most cases lower-value fish).”

“While U.S. fishermen catch enough salmon to satisfy 80 percent of our domestic demand, 70 percent of that catch is then exported instead of going directly to American grocery stores and restaurants,” said Dr. Kimberly Warner, report author and senior scientist at Oceana. “It’s anyone’s guess how much of our wild domestic salmon makes its way back to the U.S. after being processed abroad. Without traceability, it is nearly impossible to follow the fish from the farm or fishing boat to the dinner plate. What we end up eating is mostly cheaper, imported farmed salmon, sometimes masquerading as U.S. wild-caught fish.”

Oceana puts the overall mislabeling rate from this sampling at 43 percent—far lower than the seven percent mislabeling rate in its nationwide survey in 2013. Why the discrepancy when the samples were only taken months apart from each other? Winter, says Oceana.

“This survey was designed to measure fraud during the winter months, when salmon was not in season and the marketplace would be shorter on supply,” Warner told NPR.

The mislabeling of seafood is a major problem within the industry—not just for salmon, but for most commonly consumed seafood. But maybe you’re wondering, what is the big deal between farmed salmon versus wild caught. The problem is that the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Sustainable Seafood Guide lists wild caught salmon, especially wild Alaskan salmon, as the best and most sustainable option when it comes to salmon. As for farmed salmon, the guide recommends you avoid it, unless you know it’s from a responsible farmed fishery. This is especially true given the fact that a significant amount of the U.S. salmon supply comes from Chilean farmed salmon, which has recently been pumped up with even more antibiotics than usual to combat a bacterial outbreak in Chile’s coastal waters.

The federal government should “require all seafood sold in the U.S., including salmon, to have catch documentation to show it came from legal sources, and to require full chain traceability that passes this key information about where, when and how seafood was caught through the entire supply chain—from the fishing boat (or farm) to the dinner plate,” says Oceana. “Providing more information to consumers about their seafood will help them make more informed decisions, whether it is for health, economic or environmental reasons.”

In the meantime, Oceana has put together four things consumers can do to avoid getting duped:

1. Ask questions: Seafood buyers should ask more questions, including what kind of fish it is, if it is wild-caught or farm-raised, and where and how it was caught.

2. Buy fresh seafood in season: You are less likely to be duped if you are buying wild-caught salmon when it is in-season, particularly in restaurants.

3. Support traceable seafood: If the seafood has a story, you are more likely to be getting what you paid for. Products that included additional information for consumers, like the type of salmon (Chinook, king, coho, etc.), were less likely to be mislabeled.

4. Check the price: If the price is too good to be true, it probably is. You may be purchasing a different fish than what is on the menu or label.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Plastic Trash Found in Arctic Ocean, Likely Forming Sixth Garbage Patch

85% of Tampons Contain Monsanto’s ‘Cancer Causing’ Glyphosate

Plastic Bags and Fishing Nets Found in Stomach of Dead Whale

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe