By Jeremy Deaton, video by Bart Vandever

The 2010 BP oil spill dumped more than 200 million gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico, where it killed billions of fish. Had things gone as planned, that oil would have fueled cars and trucks, worsening climate change, which is going to kill billions of fish — and that was the best-case scenario. In short, oil is bad for sea life.

Except sometimes it’s not.

That’s because the legs and bracings holding up oil platforms are the ideal setting for ocean reefs. Fish like to gather around the pylons, which are covered in mussels, barnacles and corals. Emily Hazelwood, who worked as a field technician after the BP oil spill, recalled learning about the reefs firsthand.

“BP had hired all the fishermen who lost their jobs to drive our boats,” she said. “Every time we would go out with them, and we would pass one of the many oil platforms, they would say they couldn’t wait to go out there fishing.”

Experts say offshore oil will peak this year as prices fall, a trend exacerbated by the coronavirus and the ongoing price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia. The slump is expected to send a growing number of rigs offline.

There is a real question as to what to do with the shuttered rigs, which can provide a safe home to ocean life. Oil platforms typically lie far from shore, so they are protected from the water pollution that empties into the ocean, Hazelwood said. They are safe from commercial fishing trawlers that gather up schools of fish out at sea.

“Stretching from sea floor to sea surface, these platforms can be as large as the Empire State Building, which provides a lot of real estate for marine life,” Hazelwood said. “That richness of life on an oil platform is just so cool. I have never seen a group of fish like that before.”

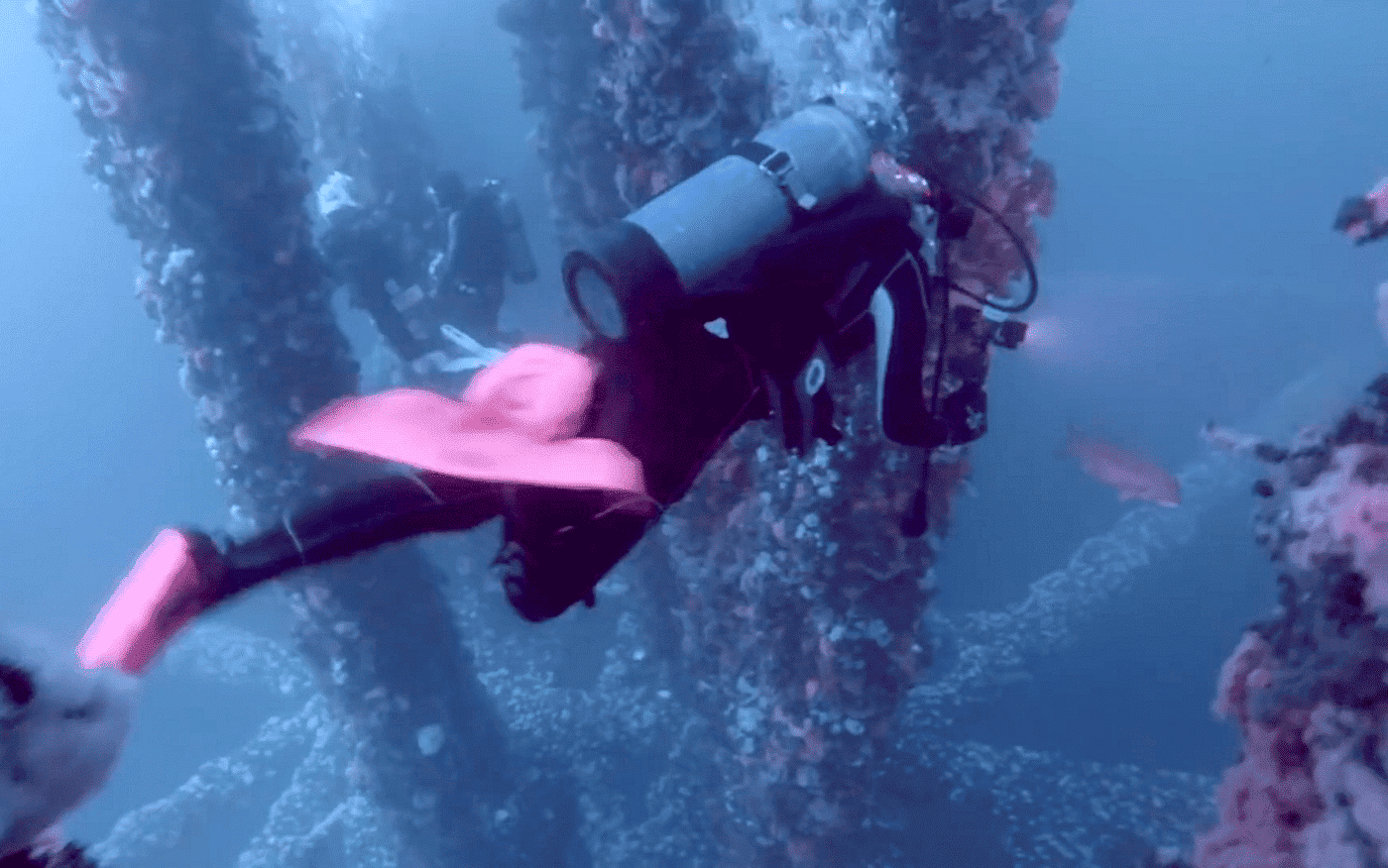

A diver explores sea life on the Eureka oil rig off the coast of Long Beach, California. Blue Latitudes

Hazelwood and her business partner Amber Sparks, co-founded consulting firm Blue Latitudes. Together, they work with oil companies to preserve the reefs that form on decommissioned oil platforms, lopping off the top while letting the rest of the structure stay in place. This process can save oil firms millions by sparing them the cost of tearing down an old rig.

Naturally, not everyone is wild about leaving the skeletons of oil platforms to rust in the ocean. In 2010, California passed a controversial law that would allow oil firms to convert old rigs into artificial reefs. Critics say it lets companies off the hook for cleanup by making the state liable for the remains of decommissioned oil platforms.

“The oil companies walk away. The state has to deal with this structure in the ocean forever, dealing with any safety issues, any pollution issues, any maintenance issues,” said Linda Krop, chief counsel with the Environmental Defense Center in Santa Barbara, California.

Divers explore sea life on the Eureka oil rig off the coast of Long Beach, California. Blue Latitudes

She said it’s also unclear if the rigs-to-reef program has much value for sea creatures. If old oil platforms become hot spots for recreational fishing, that could leave reefs mostly barren of marine life.

“We don’t know what benefit will arise from leaving a platform at sea. We want that studied. That’s what the current law requires. But the proponents are trying to weaken that part of the law,” she said.

Hazelwood and Sparks, for instance, have called for streamlining the rigs-to-reef program to make it easier for oil companies to convert old platforms into ocean habitats. They say that tearing down viable reefs just doesn’t make sense.

“Most environmental groups, they want to go back to the way the world was 10,000 years ago. And who wouldn’t? I mean, that would just be an unbelievable planet to live on,” Hazelwood said. “But that’s not necessarily the reality of our situation right now, so we advocate for finding that silver lining.”

Reposted with permission from Nexus Media.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe