Fear and Fury in Michigan Town Where Air Force Contaminated Water

Monitoring wells stand as silent sentinels on the grounds of a fire training site at Wurtsmith Air Force Base. Chemicals used at the site have contaminated nearby groundwater, rivers and lakes. Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton

Anthony Spaniola knew something was off with his town’s water. He read accounts in the Detroit Free Press and attended community meetings hosted by state health and environment agencies. Until last summer Spaniola was concerned but didn’t think the situation was out of control.

Then he saw foam on Van Etten Lake.

The unsightly ivory-colored meringue that rimmed the shore is a visible illustration of an ongoing national health and environmental disaster related to perfluorinated compounds. PFAS, as this group of chemicals is collectively called, are used to manufacture rain-repelling, stain-deflecting, heat-resisting consumer and industrial products like Teflon skillets, Gore-Tex jackets and fire retardants. There’s a good chance that every home in America has products strengthened with one of the compounds.

Spaniola and his family own a home on the east side of Van Etten Lake, a civic centerpiece in a town, nicknamed Paddletown USA, whose economy and identity is built around northern Michigan’s natural bounty of lakes and rivers.

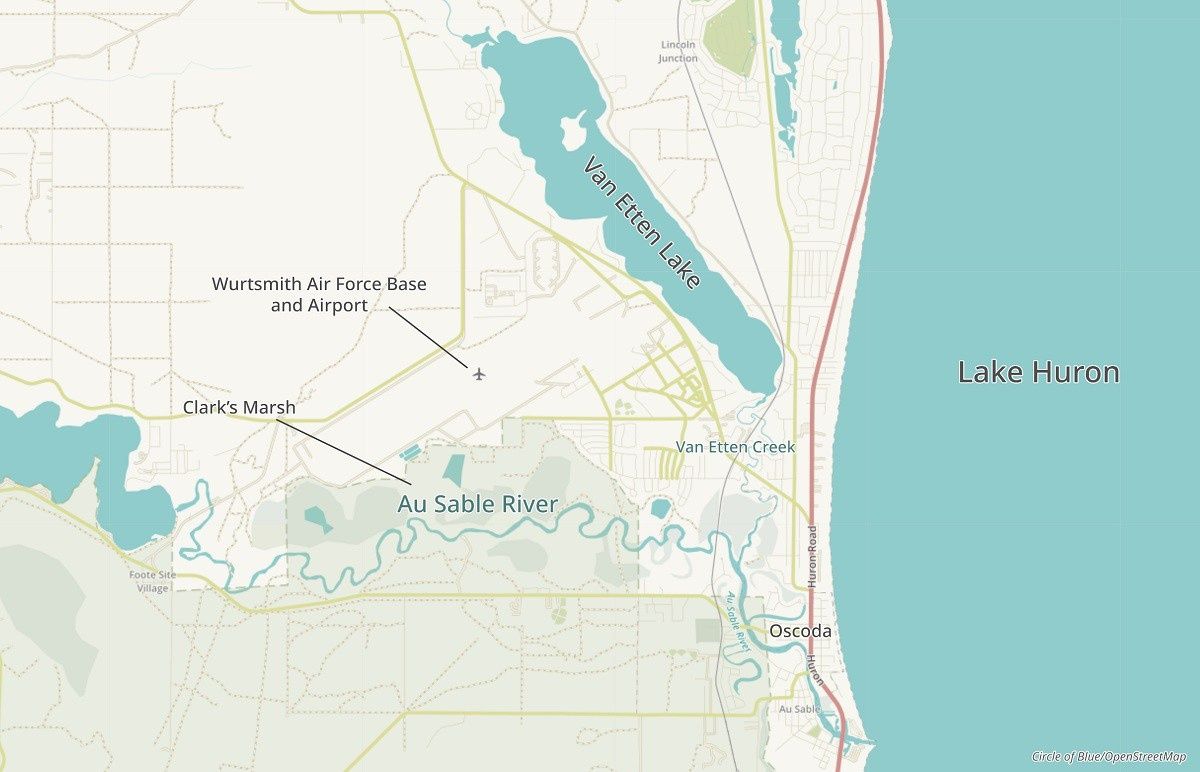

East of Oscoda is teal-hued Lake Huron, one of North America’s Great Lakes. To the west is the Au Sable River, renowned for its cold water trout fishery and a 120-mile canoe race every July through unbroken forest that attracts paddlers from across the U.S. and Canada.

And to the north, ringed by modest vacation cottages, recreational camps and family homes is Van Etten Lake. Summer winds naturally froth the shore, according to those who live here. But what appeared last July and August, and throughout the fall, was unusual. Spaniola described the foam as sticky.

Greg Cole, who manages the dam at the lake’s outlet, took pictures of the rumpled mass bunched against the barricade. Laboratory tests indicated worrisome concentrations of perfluorinated chemicals, at levels thousands of times higher than a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) health warning for drinking water.

Some studies have found that over decades of low-level exposure in drinking water—in parts per trillion even—the chemicals are associated with a higher risk of kidney and testicular cancers, thyroid disease, high cholesterol, hormone disruption and other ailments. Developed for durability, they do not easily break down once set loose from the production line.

In Oscoda the source of contamination is well documented. The chemicals are flowing underground, mostly unimpeded, from the former Wurtsmith Air Force Base where PFAS compounds, sprayed for decades during training exercises to extinguish petroleum fires, soaked into the groundwater. The closer regulators look, the more they find groundwater contaminated with PFAS, not just in Oscoda, but nationwide on military bases and industrial sites, and in towns that border them.

Wurtsmith’s location, a mile from Lake Huron and abutting Lake Van Etten is not exactly a hilltop. But it is one of the highest points in Oscoda. That’s a problem because water—and groundwater—runs downhill. And downhill from Wurtsmith is Van Etten Lake, which flows into Van Etten Creek, which joins with the Au Sable River before emptying into Lake Huron.

For years Wurtsmith, which closed in 1993, has been recognized as one of the most polluted places in Michigan. The EPA proposed designating the base as a national Superfund site in 1994, but it was never officially listed. The EPA withdrew its oversight in 2016, leaving the Air Force and state agencies to handle the cleanup while the town and county redeveloped parts of the base. The public library is located there, as are homes, churches, play fields, a plastics manufacturer, an airplane maintenance company and a healthcare facility.

But groundwater contamination from PFAS and other toxic substances below the new facilities spreads largely unchecked. The steady dose of chemicals into the area’s natural riches has upended lives in Oscoda. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality says that people should not eat fish that live year-round in the lower Au Sable River and in Clark’s Marsh, a wetland adjacent to the base where some of the highest chemical concentrations have been measured.

Drinking water is affected, too. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services has told more than two hundred households near Van Etten Lake that are on private wells not to drink their tap water. The state is providing bottled water or faucet filters, and the town is using federal grant money to extend public water to some of the homes.

But even the public water supply is at risk. Traces of the chemicals are now found downstream, in Lake Huron, the source for the regional water system. It is even in the treated water, at a few parts per trillion, that is supplied to 14,000 homes.

Current and former Oscoda residents and veterans who served at Wurtsmith have stories of odd cancers and a profusion of illnesses that have stumped doctors looking for a cause. They wonder if their ailments are connected to the relatively unstudied toxic residues in soil and water. They hope to be included in an upcoming Centers for Disease Control and Prevention assessment of PFAS exposure on military bases that could confirm or reject their fears.

After seeing the lake foam this past summer, Spaniola felt that the agencies responsible for managing the contamination were not as much in control as he had thought. “My antennae went up,” said Spaniola, a business lawyer who has immersed himself in chemical literature. “This stuff is everywhere.”

More and more people in Oscoda are coming to that conclusion. They see delays in promised cleanup actions. They read news reports from other parts of Michigan and outside the state of PFAS contamination from military bases and factories. They worry about being forgotten in the jumble. After seeing their town’s magnificent waters tarnished and neighbors getting sick, they’re starting to speak out against a system that is failing to accomplish what they want most: stopping the flow of contaminated groundwater from the base.

New Activists

On a chilly evening in mid-March about 60 people file into the Oscoda VFW building to listen to a law firm’s pitch. The meeting was called by the Veterans and Civilians Clean Water Alliance, a group of about 1,800 Wurtsmith veterans and family members whose goal, according to its founder James Bussey, is to get health care coverage for people who were sickened while living on the base. The group is considering a class-action lawsuit against 3M, the company that produced the firefighting foam.

The alliance is one of several community groups that have formed in the last few years to inform residents and demand action.

Arnie Leriche, a veteran who did not serve at Wurtsmith but lives in Oscoda, lobbied the Air Force to restart a community advisory board that had been active in the decade after the base closed. The first meeting was Nov. 1, 2017, and Leriche was voted co-chair.

“The community needed to be a part of the equation,” he told Circle of Blue.

Arnie Leriche, standing, talks with two men at a community meeting to discuss PFAS contamination. Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Greg Cole and Cathy Wusterbarth head the local group Need Our Water. They hope it will be a source of information about a highly technical issue for a community that, despite the years of testing, still seems to be relatively unaware of the PFAS contamination, Wusterbarth said. After hearing the questions posed by some residents at the VFW meeting, she feels like there is still much work to do.

“None of us has done anything like this before. We’re new activists,” Wusterbarth, who used to lifeguard on Van Etten Lake, told Circle of Blue.

Paradise Lost

Greg and Vicky Cole sit at their kitchen table, flipping through photos of guests who have stayed at the three cottages on their property at the south end of Van Etten Lake. Clients come for the fishing: northern pike, black crappie, walleye, blue gill, perch and more. “They’re from Ohio,” Vicky says, pausing over one photo with three generations of family members. “They said, ‘It’s a piece of heaven, a piece of heaven.’ That’s how I’ve always referred to it: I live in heaven.”

Between them, against the wall, is a Culligan water cooler, a noticeable reminder that their heaven, just a quarter-mile from the base, has changed.

In October 2016, the Coles received a letter from the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. Testing of their well water showed traces of PFAS compounds, but at levels lower than the EPA’s health advisory of 70 parts per trillion in drinking water. That advisory, however, applies only to the two most well-known PFAS compounds. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of others.

The health department, taking a cautious approach, said in the letter not to drink the water, cook with it, wash vegetables, or brush teeth unless the water was filtered through a reverse osmosis system. After three months in which Greg hauled drinking water from a clean tap at the town hall, the state said it would pay for one faucet filter or in-home water deliveries. The Coles chose Culligan.

The Air Force, following protocol, paid for replacement water only for homes that tested above the EPA standard. To this point, it has aided only one home in Oscoda.

Greg and Vicky Cole sit at their kitchen table. Between them is their Culligan water jug. Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

Extinguishing One Problem, Igniting Another

Wurtsmith existed as a military aviation site in various forms since 1923. After the Air Force Strategic Air Command took over operations in 1953, one of the base’s main function was to host a fleet of loaded B-52 bombers and other aircraft ready to take immediate flight in response to a nuclear attack. At the end of the Cold War, and no longer considered essential, Wurtsmith was placed into an economic redevelopment process called base realignment and closure, or BRAC.

Wurtsmith is one of 393 U.S. military installations, active or BRAC, where the Department of Defense reports a known or suspected release of PFAS compounds into water and soil. Through February 2018, the Air Force alone had spent more than $210 million on site investigations and cleanup activities for PFAS. Future cleanup liabilities for the Defense Department could run into the billions, according to government figures. The expense could soar if the government has to start paying out health claims similar to the $2.2 billion awarded in 2017 to veterans who served at Camp Lejeune, a Marine base in North Carolina whose water was laced with a different lineup of cancer-causing chemicals.

In a Feb. 29, 2016 letter, Robert Wagner, chief of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s remediation division, asked David Strainge, then the BRAC environmental coordinator, to “prevent further off base movement” of PFAS contaminated groundwater because it was affecting well water. The letter said that the Air Force must 1) monitor residential wells for PFAS; 2) define the boundaries of the contamination plume; 3) monitor the plume’s movement off base; and 4) deliver a cleanup plan to DEQ.

The Air Force’s response on March 18, 2016, stated that it would comply with any applicable state and federal laws. The letter outlined the actions that the Air Force had taken to date. Officials began investigating PFAS contamination stemming from the former fire training site in 2012, after Michigan DEQ tests of fish in Clark’s Marsh, downhill from the training site, showed high levels of the chemicals, more than 15 times the state limit. PFAS were in firefighting foams that were used starting in 1970. The Air Force said it did not know about their toxic potential until the EPA initiated a production phase out of the two most known chemicals in 2000. By that time, Wurtsmith had already closed.

The Air Force claimed in the March 18, 2016 letter that testing in 2012 determined that PFAS contaminated groundwater was contained on the base.

That turned out not to be the case. Subsequent testing has revealed traces of the chemical from at least 16 sites on the former base while the chemical plume has spread throughout the waterways around Oscoda. The Air Force built a treatment plant in 2015 to filter pollution coming from the fire training site, which is now an open field studded with monitoring wells.

But more than two years after the exchange of letters in the spring of 2016, the Air Force has finalized no additional actions to halt the advance of the contaminated plume. Matt Marrs, the current BRAC environmental coordinator, told Circle of Blue that a second treatment unit will come online by August 2018. The Michigan DEQ had ordered that facility to be completed by the end of 2017.

The treatment systems are a page from a well-worn playbook. Groundwater contamination, of all sorts, is the primary focus at Wurtsmith. The first chemicals to attract scrutiny at the base, back in the 1970s, were the chlorinated solvents TCE and vinyl chloride. A number of treatment systems dot the grounds.

Cleanup for those chemicals is, in a twist, spreading PFAS contaminants farther afield. Since 1981, so-called “pump and treat” systems have been drawing groundwater from the base, stripping it of chlorinated solvents, and discharging it into the base’s storm sewer, which empties into Van Etten Creek. Marrs told Circle of Blue that the three-unit system does not remove PFAS compounds. Instead, they go into the storm sewer, then into the creek before being carried downstream. A spokesman told Circle of Blue that the Air Force has tested the outfall as discharging water with 800 to 1,002 parts per trillion PFAS. Locals call the treatment systems “pump and dumps.”

Water from the Wurtsmith storm sewer pours into Van Etten Creek. The water smells strongly of benzene. Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

The military and the state are now in a dispute about the scope of the cleanup and which standards should apply to PFAS compounds found in Van Etten Lake, Van Etten Creek and the Au Sable River. The state standard for surface water not used for drinking is 12 parts per trillion of PFOS, a main ingredient in the firefighting foam. The Michigan DEQ notified the Air Force in a Dec. 14, 2017 letter that the treatment systems were inadequate. They are in a private resolution process that neither side will discuss publicly.

Oscoda residents are furious that the state has not been more forceful. To some extent, though, many of those residents bear at least some of the responsibility. Iosco County, home to Oscoda, is a rural Republican domain. A majority of voters cast their ballots for conservative state and federal administrations that have exhibited fealty to deregulation, animus to environmental enforcement, and disregard for investing in initiatives that protect public health. Michigan, after all, is where the Republican governor and his aides ignored warnings of contamination in the water supply for residents of Flint. To a large extent a political mismatch exists between what Iosco County residents want from government and who they helped elect to key government offices.

It’s hard, in fact, to discuss water contamination in Michigan these days without conversation turning to Flint. Oscodans frequently mentioned that city’s lead contamination and the slow state response. When they began holding meetings on PFAS in Oscoda, Spaniola thought state agencies might have learned something from the Flint crisis. After seeing the delays in response, he no longer has that opinion.

“I’m speechless with the lack of urgency I’ve seen in dealing with this issue,” Spaniola said.

Just as with the Flint water crisis, the DEQ has failed to enforce its water pollution standards. Nearly a year ago, at an April 25, 2017 meeting, Air Force officials asked the DEQ for a letter clarifying the cleanup standards that apply. The response has been shuttled from DEQ to the governor’s office to the attorney general’s office, but according to the last available documents from base cleanup meetings it has not yet been delivered. The attorney general’s office did not respond to repeated phone calls asking about the letter’s status.

Aaron Weed, the town supervisor, has asked to meet with the director of the Michigan DEQ but no meeting has taken place. What would he request? “I’d say that action needs to be taken,” Weed said.

The DEQ did not allow its field staff who are working on the Wurtsmith case to speak with Circle of Blue for this story.

Air Force officials, meanwhile, say they can only work with the money that is allocated to them. Congress appropriated an additional $84 million in the recent budget for PFAS cleanup, but directed it at naval bases. “We’re in fiscally constraining times,” Marrs said. “All BRAC bases are competing for limited funds.”

The situation is not entirely hopeless. Soon the Coles and about 30 other homes will be able to hook into the public water system. Oscoda received a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to extend the water main down their road. Homeowners who want to connect—it is not required—will have to pay to install a service line from their home to the main, which could run more than $1,000.

Weed, the town supervisor, told Circle of Blue that he’s looking “for anyone who can write us a check” for $4 million to extend public water to another 230 homes affected by the plumes. Weed, like most Oscodans, had to educate himself quickly on PFAS chemicals once he found out they were disrupting the town. He took an online college course on environmental science.

Not even the public water system, however, is immune from the threat. In a sign of how far the contaminants have traveled, testing of treated water from Huron Shores Regional Water Authority, the local water system, in 2016 showed a range of results: from no detection up to 27 parts per trillion of PFAS. The authority’s Lake Huron intake is about a dozen miles south of the mouth of the Au Sable.

A measurement in parts per trillion is almost inconceivably tiny. Imagine this: count back one trillion seconds in the course of human history. How far does that reach? More than 30,000 years ago, long before people tamed dogs or started row-cropping plants. Measurements in parts per trillion, essentially, are a sneeze in the span of human civilization.

Yet those sneezes are enough to worry public health professionals, who have convinced officials in Minnesota, New Jersey and other states that the EPA’s guidelines are not strict enough to guard against long-term health risks.

Those risks are the town’s worries, too. Residents are concerned that tourism may take a hit unless officials “stop the bleeding coming from the base,” as Greg says. The Coles say that their cottages aren’t booked up for the summer as they usually are by mid-March. The ordeal has changed their outlook and redirected their attention.

“I thought we were all set,” Greg said, about life on their property. “We’ll probably stay here. But now my passion comes from what I’ve seen. Even when we get city water, I’m going to fight for cleanup so that the next generation, the kids and grandkids can enjoy it.”

Veterans and community members came to a March 12, 2018 meeting at the Oscoda VFW to discuss PFAS contamination.Brett Walton / Circle of Blue

They aren’t the only Oscodans who feel a sense of loss, a disruption of place. For those aware of how deeply the chemicals are embedded in the area’s waters, home is not what it used to be.

Tressa Thompto grew up in Oscoda and lived here until 1982. Her husband served in the Air Force and was stationed at Wurtsmith for four years starting in 1978. They now live in Des Moines, Iowa, but Tressa returned to the area for the meeting at the VFW. Her husband was diagnosed in 1991 with oligodendroglioma, a type of brain tumor. The growth, the size of her fist almost, was found behind his left eye.

“I have five brothers and sisters and we all wanted to come back here someday. But the way it is now … ” Her voice trails off, then she picks up the thread again. “I always wanted to come back here, but it’s like the town has been damaged by this.”

Tressa’s sister still lives in Oscoda, in a house on Van Etten Lake. She had planned to stay with her while in town for the meeting, but she ended up staying with her brother in Alpena, an hour drive to the north. She couldn’t bear to stay so close to the lake, whose waters now carry new meaning. “I couldn’t do it,” she said.

Trump Administration Sued for Suspension of Clean Water Rule https://t.co/65gwNGTOFE #CleanWaterRule @Earthjustice @NRDC @350 @SierraClub @greenpeaceusa @foe_us @Waterkeeper

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) February 7, 2018

Reposted with permission from our media associate Circle of Blue.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe