Hurricane season is upon us — and this one could be a doozy.

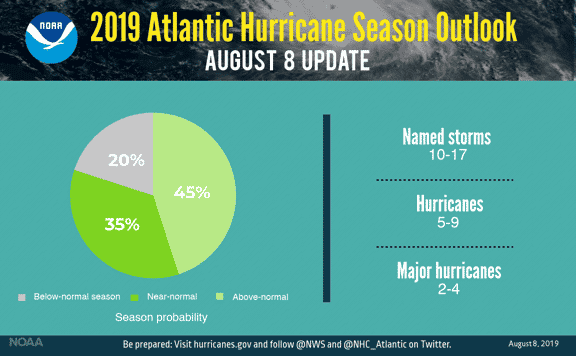

After initially predicting a pretty typical Atlantic hurricane season, in terms of the number of expected named and major storms, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently revised its forecast, increasing the likelihood of an above-average hurricane season from 30 percent to 45 percent. This means residents of the Caribbean and those living along the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico coastlines shouldn’t let their guard down — and forecasters warn, there appears to be an increased chance of more major hurricanes:

The overall number of predicted storms is also greater with NOAA now expecting 10-17 named storms (winds of 39 mph or greater), of which 5-9 will become hurricanes (winds of 74 mph or greater), including 2-4 major hurricanes (winds of 111 mph or greater). This updated outlook is for the entire six-month hurricane season, which ends Nov. 30.

There’s little evidence to suggest that climate change actually creates more hurricanes. Indeed, NOAA itself explains that the revised forecast has more to do with diminished El Nino activity in the Pacific.

But there is abundant information indicating our changing climate is supercharging more and more of the ones that do form. And from Hurricanes Maria and Irma to Michael and Harvey, these storms are bringing almost unimaginable devastation much more frequently as a result.

Read on to discover how the climate crisis makes an already tough situation worse for millions of people all around the world.

Adding Fuel to the Fire

Carbon pollution from burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas is warming our planet and driving climate change. It’s throwing natural systems out of balance — to often devastating effect.

One result among many is that average global sea surface temperatures are rising — and when sea surface temperatures become warmer, hurricanes can become more powerful.

“For a long time, we’ve understood, based on pretty simple physics, that as you warm the ocean’s surface, you’re going to get more intense hurricanes. Whether you get more hurricanes or fewer hurricanes, the strongest storms will tend to become stronger,” Dr. Michael Mann, distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University and author of The Hockey Stick and The Climate Warsand The Madhouse Effect, explained to Climate Reality.

“Empirical studies show that there’s a roughly 10-mile-per-hour increase in sustained peak winds in Cat 5-level storms for each degree Fahrenheit of warming.”

Warmer oceans – especially deep ocean waters — can also allow storms to intensify quickly. So a once-relatively weak storm can cross the right stretch of (warm) water and become a major hurricane in a matter of hours.

With storms and forecasts changing fast, people can be under-prepared for the true intensity of the actual hurricane that makes landfall, potentially resulting in greater damage and even loss of life.

But looking at increases in sustained wind speed alone doesn’t paint the full picture of a storm’s destructive potential. A hurricane is more than just its winds — it’s a major rainfall event accompanied by dangerous storm surge.

>> Free Download: Extreme Weather and the Climate Crisis <<

More and More, Water is the Real Story

“Other influences being equal, warmer waters yield stronger hurricanes with heavier rainfall. The tropical Atlantic Ocean has warmed over the past century, at least partly due to human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases,” according to NOAA. “Most models agree that climate change through the twenty-first century is likely to increase the average intensity and rainfall rates of hurricanes in the Atlantic and other basins.”

The bottom line: warmer temperatures create a greater chance of more intense storms.

This makes a lot of sense when you consider two facts:

1. Warmer air holds more moisture.

2. Higher temperatures evaporate more water from the surface of our oceans.

Taken together, these factors mean there’s more water vapor for hurricanes to suck up as they travel over the sea surface, and more capacity to hold on to it. So when they make landfall, all that extra moisture returns to the Earth’s surface as heavy precipitation.

At the same time that hurricane winds are getting exponentially stronger and the rain they carry is becoming heavier, sea levels are rising too. With higher seas, the storm surges from hurricanes (think: abnormally large waves driven to shore by hurricane winds) get higher too and move further inland.

The result: More water falling from above and more coming in from the ocean, hitting the coast harder and harder from both directions.

In the case of the Category 4 Hurricane Harvey last year, “sea surface temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico that [were] 2.7 – 7.2°F (1.5 – 4°C) above average” helped power a storm that dumped more than 60 inches of rain over parts of southeastern Texas. The highest-reported storm surge from Harvey (in Port Lavaca, Texas) was 7 feet above the mean sea level.

After all was said and done, the resultant catastrophic flooding and other storm damage made Harvey the second-most costly hurricane in U.S. history, behind only Hurricane Katrina. Plus, 68 Texans lost their lives, the most direct deaths from a tropical cyclone in the state since 1919.

The National Hurricane Center called the storm “the most significant tropical cyclone rainfall event in US history.”

Learn more: Climate Change and Health: Hurricanes

Take Action

So, is climate change really making hurricanes more dangerous?

The simple answer is yes.

But it’s not all bad news — because we can solve the climate crisis. And we will.

Learn how in Climate Reality’s™ free e-book, Extreme Weather and the Climate Crisis: What You Need to Know.

In it we explain in plain language how burning fossil fuels is driving a climate crisis and making our weather more intense and dangerous. And it’s not just hurricanes, either. Wildfires. Flooding and drought. Extreme heat. This crisis is creating many kinds of wild weather all over the globe.

We also share stories about how extreme weather is affecting people just like you, in their own words — as well as ways you can join the climate movement and make a difference today.

- Florida Prepares for 'Extremely Dangerous' Dorian to Make Landfall ...

- Preparing for Hurricanes: 3 Essential Reads - EcoWatch

- Tropical Storms Are Getting More Intense Due to the Climate Crisis - EcoWatch

- 2 Hurricanes Could Strike U.S. on the Same Day for the First Time in History - EcoWatch

- 2021 Hurricane Season: NOAA Predicts More Storms Than Usual

- Hurricane Larry Forms in Atlantic, Could Become ‘Major’ Storm

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe