While it’s difficult to assess exactly how dangerous many prep plant chemicals are, that’s especially true of a substance called polyacrylamide.

But things changed in late 1998, when by Browning’s account, the prep plant where he worked started making more frother—and consequently, using more chemicals. He’d be bulldozing the piles of treated coal, and the fumes would come in through the heater. Browning contends that these fumes started affecting his health almost immediately; his mouth would hurt and he got the shakes. Three weeks in, Browning said he complained to his supervisor, but nothing changed.

Finally, about six weeks after his symptoms started, Browning and a coworker were rushed to the emergency room. That was his last day of work, after 29 years in the coal industry.

“The last day I worked, at noon, they brought me a respirator. It was too late for me,” he said.

Browning isn’t the only worker who claims he wasn’t told the whole story about how to be safe around chemicals in the workplace. Price and other plaintiffs in the Marshall County lawsuits say they weren’t provided with appropriate protective gear, and didn’t know for years what chemicals they were using.

“They never mentioned toxins down there, chemicals. That was never, never, never mentioned. Never had a safety meeting on that,” Browning said.

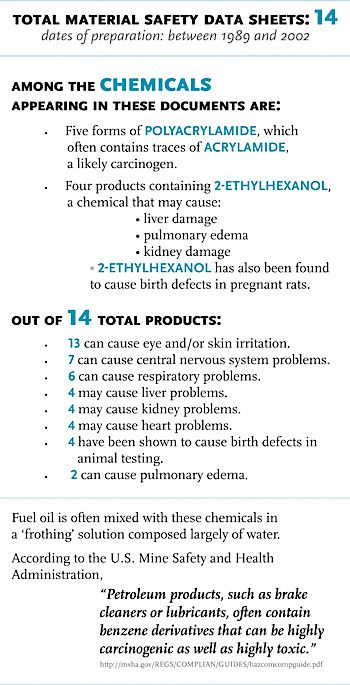

Price agrees. “We never did have no idea what [it] was,” he said, referring to many of the frothing chemicals. “We was never told or never shown any safety data sheets on it, so we could look ourselves and see what it contained.”

Failing to provide this information would be illegal. But industry representatives dispute these claims.

Nancy Gravatt, senior vice president of communications for the National Mining Association, countered that prep plant employees are properly informed about the chemicals they’re using, and that MSDSs “are posted both for reading at any time and available in the event of an emergency.” She added that employees “are trained on the substances brought onto property” at these plants.

However, Phil Smith of the United Mine Workers said he’s not surprised that workers may not have had access to the data sheets.

“We keep our members informed about all the chemicals that are used in coal preparation plants, and if worked with properly, they’re safe,” Smith said. But, he said, he believes nonunion operations are less likely to inform their employees regarding chemicals and their safety hazards. (Employees are never required to wear safety equipment, Smith pointed out.)

Employee access to data sheets isn’t the only point of contention between workers and the industry. Another question that’s difficult to answer is just how high workers’ chemical exposure really is. Gravatt said that MCHM is used at safe concentrations.

“Typical dosage rates for frothers like MCHM are less than 12 parts per million. In other words, a few hundred cubic centimeters per minute enter into 8 to 10 thousand gallons per minute of coal slurry,” Gravatt wrote in an email. This is higher than the CDC’s recommendation of no more than 1 part per million of MCHM in drinking water. But Gravatt said there’s a difference.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe