Groundwater Disappearing Much Faster Than Lake Mead in Colorado River Basin

The mineral-stained canyon walls and the plunging water levels at Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, are the most visible signs of the driest 14-year period in the Colorado River Basin’s historical record.

But the receding shorelines at the Basin’s major reservoirs—including Lake Mead, which fell to a record-low level this month, and Lake Powell, the second largest reservoir on the Colorado, 290 kilometers (180 miles) upstream from Mead—are an insignificant hydrological change compared to the monumental disruption taking place underground.

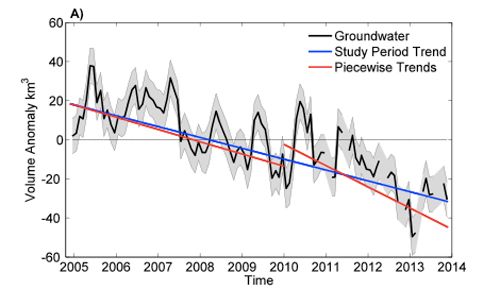

Satellite data show that in the last nine years, as a powerful drought held fast and river flows plummeted, the majority of the freshwater losses in the Basin—nearly 80 percent—came from water pumped out of aquifers.

The decrease in groundwater reserves is a volume of water equivalent to one and a half times the amount held in a full Lake Mead, according to a study published today in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“We didn’t think it would be this bad,” said Stephanie Castle, a researcher at the University of California, Irvine, and the study’s lead author. “Basin-wide groundwater losses are not well documented. The number was shocking.”

Scales in the Sky

The research team used data from the GRACE satellite mission to calculate the water balance for a Basin that spreads across seven states and reaches into Mexico.

Launched in 2002, GRACE is a pair of satellites that translate fluctuations in the Earth’s gravitational pull into changes in total water storage. Separate data sets are used to pull apart the contributions from snowpack, soil moisture, surface water and groundwater. GRACE data has been used to assess groundwater depletion in California and the Middle East, as well as flood potential in the Missouri River Basin.

Jay Famiglietti, an Earth systems professor at the University of California, Irvine, and a study co-author, calls the instruments “scales in the sky.”

For the study, the researchers looked at the period from December 2004 to November 2013. This time frame allowed them to isolate the effects of the drought on groundwater. By 2004, the Basin’s reservoirs were nearing record lows. Today, they are slightly, but not significantly lower, at 51 percent full.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe