Endangered Migratory Birds on Collision Course with New Airport Construction in Philippines

The black-faced spoonbill (Platalea minor), a rare, large waterbird classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. spaceaero2 via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 3.0

A new airport under construction in a key wetland habitat just north of the Philippine capital is poised to impact dozens of migratory bird species, many of them already threatened, observers say.

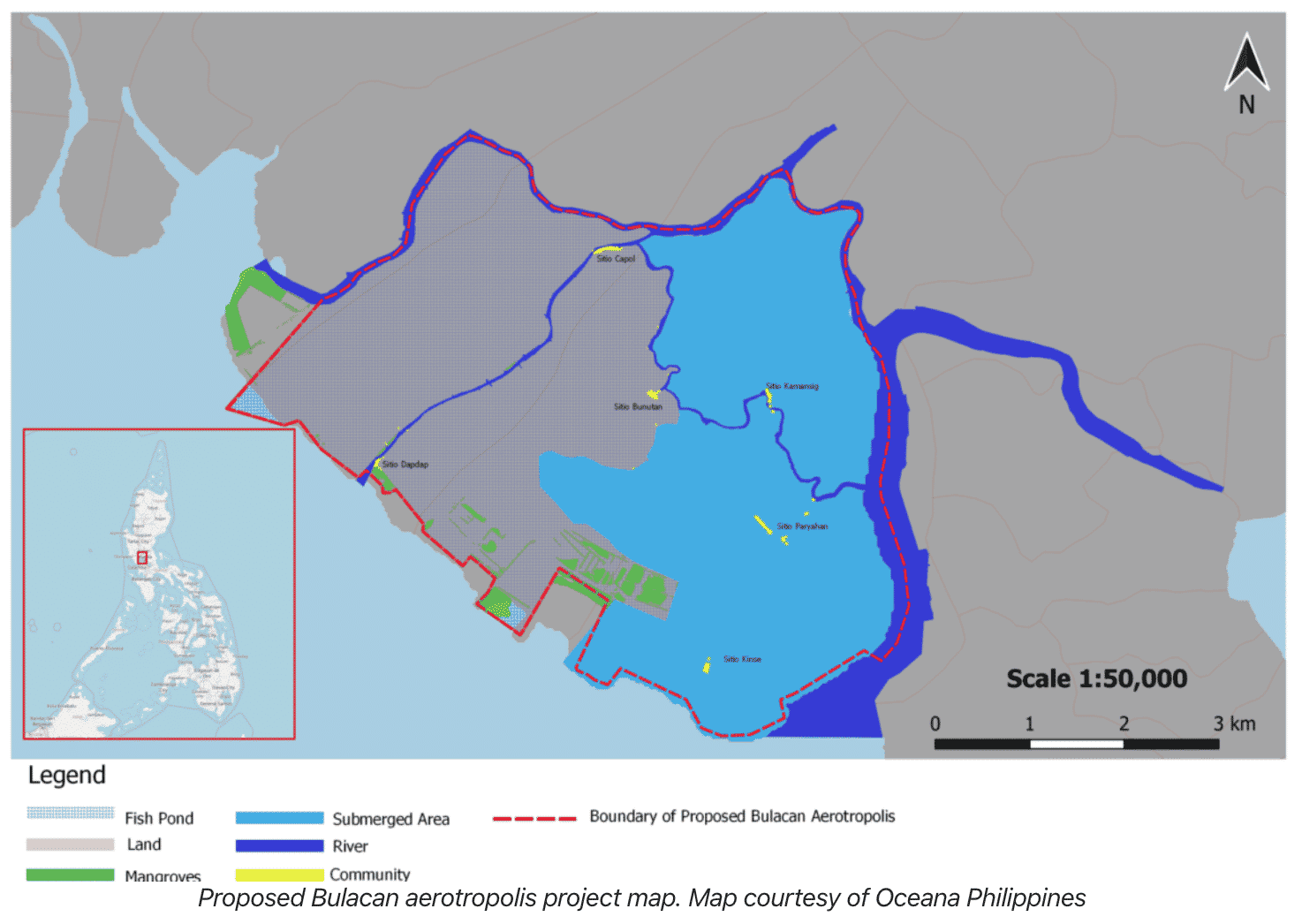

The 2,500-hectare (6,200-acre) “aerotropolis” complex in Bulacan province, 25 kilometers (16 miles) from Manila, is part of a wider infrastructure development push that will reclaim nearly 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) of wetland in Manila Bay.

But at least 12 currently threatened or near-threatened bird species would be affected by the airport project, according to the Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP), a national association of bird-watchers. This includes the black-faced spoonbill (Platalea minor), a rare, large waterbird classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List. A frequent visitor of mudflats, the spoonbill has an estimated global population of 2,250 individuals, according to BirdLife International.

“Out of the 50 million migratory birds that pass through the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, about 27% pass through the Philippines,” Cristina Cinco of the WBCP said at a press conference at the end of January. “We’re talking about 60 migratory species and we have 12 that need to be protected.”

The figures come after the annual Asian Waterbird Census conducted from Jan. 11 to 19 this year, during which birders from the WBCP recorded 24 black-faced spoonbills at the location of the future airport — the first time in more than a century that the endangered species has been observed in Manila Bay. It’s also the single biggest flock ever recorded for the species in the country, Cinco says.

Proposed Bulacan Aerotropolis

The 745.6 billion peso ( billion) Bulacan airport project by San Miguel Corporation (SMC), the biggest company by revenue in the Philippines, is among the 22 reclamation projects planned for Manila Bay, the Philippine capital’s center of navigation, trade and commerce. Approved under President Rodrigo Duterte’s “Build, Build, Build” program, the airport is the country’s most expensive infrastructure project to date. It’s expected to help ease air traffic at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) and accommodate 100 million passengers per year. But unlike other reclamation projects in the bay, which are at varying stages of approval, the aerotropolis has already been greenlit and had its ground-breaking on Jan. 15.

It’s not just the spoonbills that are at risk from the airport project, Cinco said. Several endangered waterbird species in the same area face the same threat. Among these are the Far Eastern curlew (Numenius madagascariensis), the largest migratory shorebird, and the great knot (Calidris tenuirostris), both endangered under the IUCN, and the vulnerable Chinese egret (Egretta eulophotes).

Near-threatened species such as the Asian dowitcher (Limnodromus semipalmatus), bar-tailed godwit (Limosa lapponica), black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa), Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata), red-necked stint (Calidris ruficollis), red knot (Calidris canutus), and curlew sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea) have also been recorded lingering around the site of the airport project and thus face the same threats.

While estimated numbers of the Far Eastern curlew are dwindling worldwide, Cinco said WBCP members saw hundreds of these shorebirds in Bulacan, which has the largest share of coastal wetland in the whole stretch of Manila Bay. Given the wetland’s ecological importance, Cinco said it should be recognized as a Ramsar site to protect the species within its domain.

An endangered Far Eastern curlew (Numenius madagascariensis) is among the migratory birds spotted in Bulacan’s wetlands. ken / Flickr

Manila Bay, which straddles five provinces, is home to more than 200,000 waterbirds during the high season, 75% of them migratory, according to a report by Arne Jensen of Wetlands International. A quarter of the critical wetlands in Manila Bay fall within the jurisdiction of Bulacan.

Every year, more than 50 million waterbirds, including 32 threatened and 19 near-threatened species, travel through the Philippines by the East Asian Australasian Flyaway, one of the world’s biggest migratory bird flight paths, according to data from the environment department. The Philippines has seven sites designated as wetlands of international importance, or Ramsar sites, which together host more than 80 species during the annual migration season.

In Bulacan, sunrises and sunsets draw in hundreds of thousands of birds, Cinco said — a good indicator of the site’s environmental importance. With the reclamation project underway, she said, the birds face displacement. “Of course when you reclaim [land], they [birds] lose their habitats. Where will they go?” Cinco said. “They will relocate, yes, but what is their effect on the flyway?”

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe