Earth’s Climate After 2030: Conditions Could Resemble Era 3 Million Years Ago, Scientists Predict

By Tim Radford

Humankind, in two centuries, has transformed the climate. It has reversed a 50-million-year cooling trend.

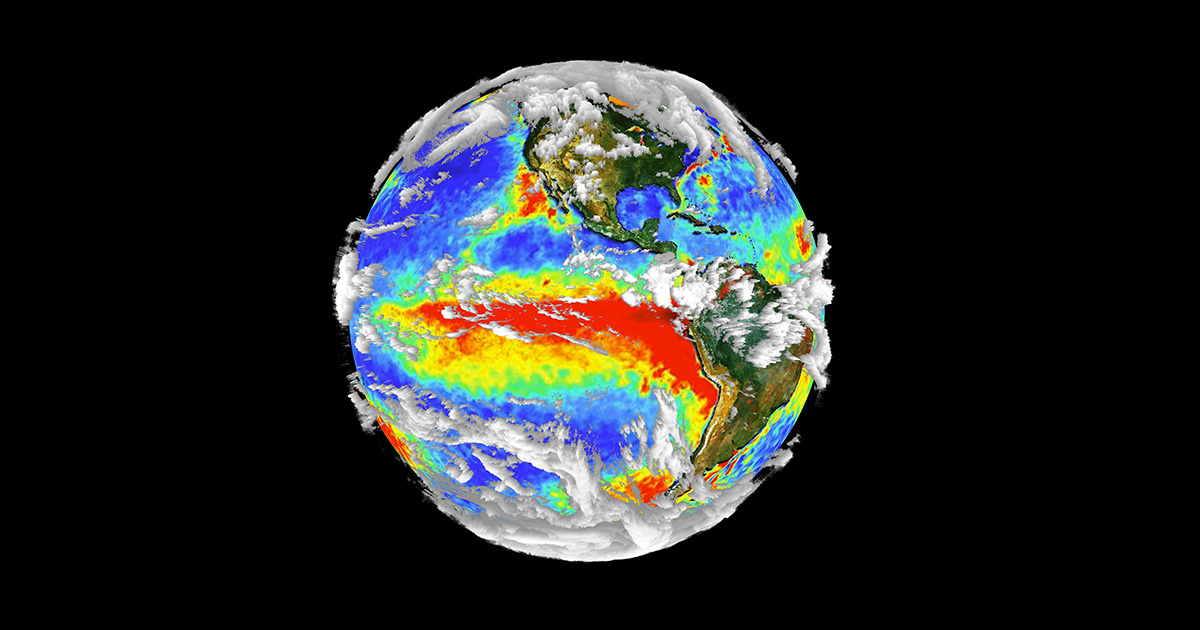

Scientists conclude that the profligate combustion of fossil fuels could within three decades take planet Earth back to conditions that existed in the Pliocene three million years ago, an era almost ice-free and at least 1.8°C and possibly 3.6°C warmer than today.

But there is a much earlier warming precedent. The Eocene planet at its warmest 50 million years ago was perhaps 13°C warmer than it has been for almost all human history.

Its continents were differently configured, the Arctic was characterized by swampy forests that might have looked a little like the Louisiana bayous of the U.S., and the first mammals had begun to colonize the globe.

And then, steadily but unevenly, the globe began to cool towards a level comfortable for human evolution, and then much later to a level that permitted the birth of agriculture and the foundation of a civilization that fostered writing, music, poetry, scholarship and scientific skills capable of tracing the detailed history of the last 50 million years and at the same time projecting a changing future.

“We can use the past as a yardstick to understand the future, which is so different from anything we have experienced in our lifetime,” said John Williams, a palaeo-ecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“People have a hard time projecting what the world will be like in five or 10 years from now. This is a tool for predicting that—how we head down those paths, and using deep geologic analogues to think about changes in time.”

Dr. Williams and his colleagues report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that they compared the climate computer forecasts for the mean summer and winter world temperatures from 2020 to 2280, with historic and prehistoric warm periods over the last 50 million years.

And they identified a hotspot in the mid-Pliocene more than 3 million years ago as the best match for global climates after 2030.

They reason that if nations fulfill the promise made in Paris in 2015 to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and keep average global warming to no more than 1.5°C above the levels for most of human history, then that is what global conditions will be like.

No Parallel

If, on the other hand, nations go on burning fossil fuels under the business-as-usual scenario, then by 2150 the world will be very like the early Eocene, 50 million years ago.

And if that is the case, at least 9 percent of the globe—including northern Australia, east and south-east Asia, and the coastal Americas—will experience what the scientists call “geologically novel climates”: that is, conditions for which the past can offer no match at all.

It is a tenet of geology that the present is key to the past. If so, the past can also illuminate the future: what has happened before can happen again.

In the course of decades of careful study, climate scientists have identified examples of mass extinction and catastrophic climate change from the Cretaceous and the Permian and even the late Carboniferous, when so much carbon dioxide was taken from the atmosphere and buried as fossil plant material that the planet almost became a snowball.

More directly, change in the past has repeatedly provided increasingly urgent warnings for the near future.

Human Flourishing Ended

So cogent have been the warnings from the distant past that researchers argue that the epoch in which modern humans flourished—geologists call it the Holocene—effectively came to an end midway through the 20th century.

What initially provided a safe operating space for emerging humanity will, they think, become known as the Anthropocene, because human activity has now so dramatically changed the climate, the landscape and the conditions under which other lifeforms flourish.

“The further we move from the Holocene, the greater we move out of safe operating space,” professor Williams said.

“In the roughly 20 to 25 years I have been working in the field, we have gone from expecting climate change to happen, to detecting its effects, and now we are seeing it is causing harm.

“People are dying, property is being damaged, we’re seeing intensified fires and intensified storms that can be attributed to climate change.”

#Scientists Warn We May Be on Track for 'Hothouse Earth' #hothouseearth #science @scifri @judiearonson

https://t.co/pwuxgMjtLJ— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) August 17, 2018

Reposted with permission from our media associate Climate News Network.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe