Why Aren’t School Buses Electric? These Coloradans Are Sick of Diesel

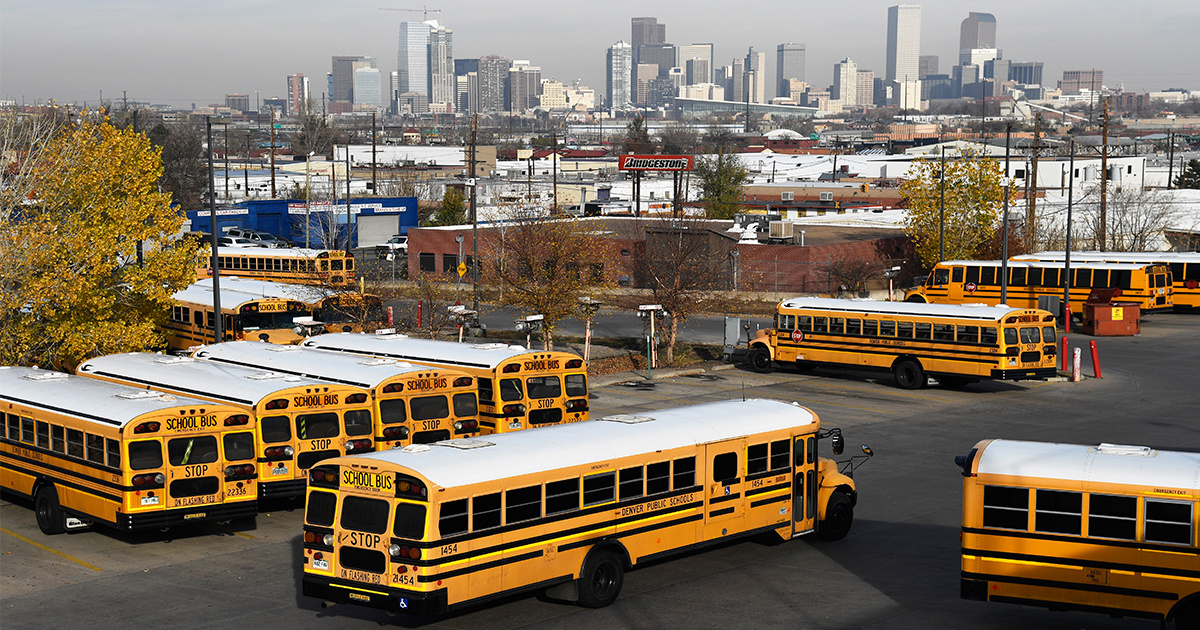

Buses head out at the Denver Public Schools Hilltop Terminal Nov. 10, 2017. Andy Cross / The Denver Post via Getty Images

By Corey Binns

Before her two kids returned to school at the end of last summer, Lorena Osorio stood before the Westminster, Colorado, school board and gave heartfelt testimony about raising her asthmatic son, now a student at the local high school. “My son was only three years old when he first suffered from asthma,” she said. Like most kids, he rode a diesel school bus. Some afternoons he arrived home struggling to breathe.

Osorio and her family live just north of Denver, where children are at particularly high risk for respiratory illnesses. Air quality there ranks among the worst in the nation, according to an American Lung Association report.

That evening at the school board meeting, Osorio stood alongside a Spanish translator working with Protégete, the Latino outreach arm of the environmental nonprofit Conservation Colorado. The group runs a Clean Buses for Healthy Niños campaign, an initiative of the League of Conservation Voters, which advocates across the country for states to trade in their diesel school buses for electric ones, particularly in communities of color and low-income areas, which suffer disproportionately from air pollution.

In Colorado, more than 4,000 yellow school buses run on diesel. They carry 42 percent of the state’s school kids and spew out nearly 50,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions a year. Each electric school bus can save districts nearly $2,000 a year in fuel and $4,400 a year in maintenance costs, according to a report by the Colorado Public Interest Research Group (CoPIRG) Foundation, Frontier Group and Environment Colorado.

Colorado school districts may now apply for state funding for a new fleet of electric buses via the Volkswagen diesel emissions cheating scandal settlement, as Osorio explained. That settlement resulted in more than $4 billion being split among 44 states plus Washington, DC and Puerto Rico for use in environmental mitigation and to promote adoption of zero-emissions technology. “It is our responsibility to clean up our contaminated air,” Osorio told the board members.

Thanks in part to the efforts of Conservation Colorado, CoPIRG, the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project and NRDC, Colorado has earmarked $18 million of its settlement funds to replace about 450 trucks, school buses, shuttle buses and other vehicles with alternative-fuel or electric vehicles. Another portion of the funds will pay for charging stations, a necessary part of the electric vehicle infrastructure.

Advocates say that improvements in our transportation sector—one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gases across the nation—are key to addressing both our changing climate and public health challenges. CoPIRG director Danny Katz noted that Denver puts out ozone alerts to urge residents to stay indoors on bad days, something he calls incongruous with the state’s reputation as a destination for nature lovers. “Air pollution is literally impacting our ability to live an active outdoor lifestyle that is central to our quality of life here,” he said. “This is especially bad for the 343,000 Coloradans with asthma, but ultimately this impacts everyone.”

Still, the momentum for change has been slow to build. For example, in Westminster, the school board has so far deemed the program impractical for its district’s use. “Given [our] size—9,500 students—and the fact that we replace, at most, one vehicle a year, the electric bus program does not make sense for the district,” said its chief communications officer, Steve Saunders. And while nearby Denver Public Schools has been in conversation about alternative fuels and electric school buses and their benefits, the district has made no purchase plans. But on the northern side of the Denver metro area, Adams County School District 12—which serves about 39,000 students across five municipalities—has applied for grants for eight buses.

Meanwhile, environmental advocates are eagerly awaiting leadership on the issue by the state’s incoming governor, Jared Polis, who was endorsed by Conservation Colorado for his record on fighting for clean air and climate action. They are also waiting for the technology itself. Blue Bird—North America’s top school bus manufacturer—delivered its first electric buses to districts in Ontario and California only this past September. (In December 2016, the corporation received $4.4 million from the U.S. Department of Energy for research and the development of a zero-emissions electric school bus using vehicle-to-grid technology by 2019.)

Despite the modest pace of the transition, however, analysts see promise: Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) estimates that in the second half of the 2020s, electric buses will take off even faster than electric vehicles, filling 84 percent of the market by 2030. As Colin McKerracher, lead analyst on advanced transportation for BNEF, noted in May, “Developments over the last 12 months, such as manufacturers’ plans for model roll-outs and new regulations on urban pollution, have bolstered our bullish view of the prospects for EVs.”

Those prospects could be further improved if fleet managers and school districts partner up with electric utilities. As NRDC senior attorney Max Baumhefner explained, utilities are increasingly looking to use the big batteries in electric school buses to lower the cost of managing a grid with large amounts of variable electricity generation like wind and solar. “Putting kids in zero-emission buses is motivation enough,” he noted, “but when those buses are stationary (which is most of the day and all night), they can be charged when wind or solar generation is abundant, and [school districts] can get paid to put that electricity back onto the grid when it is most needed.”

Grassroots groups are poised to play a big role in electric bus adoption in Colorado. During the past two years, Protégete has worked hard to bring attention to the issue in the Latino community in Denver. Juan Pérez Sáez, one of the group’s community organizers, led a team in collecting comments from Latino residents and bringing people to the state’s public hearings. Some described how high housing prices forced them to live, work and play in the city’s industrial outskirts, next to highways and near factories and refineries, where dirty air is a daily fact of life and asthma rates are high.

In fact, as Pérez Sáez noted, asthma is a leading cause across the U.S. for absenteeism in schools. “It means children are not having the opportunity to be educated in an environment that is safe for them,” he said, “and that should be a priority for everyone.”

In July, Pérez Sáez traveled with fellow community members and environmental justice leaders from Nevada, Arizona and Colorado to the Rally for Clean Air in Santa Fe, New Mexico, a state that has seen increasing air pollution yet little progress on electric school buses or other climate action under the outgoing Republican governor, Susana Martinez. Under Martinez, the New Mexico Environment Department has argued that electric buses wouldn’t be a cost-effective use of its VW settlement funds, despite the fact that 1 out of every 11 of the state’s children has asthma.

The rally took place as Martinez and other state lawmakers were gathering for an annual meeting of the National Governors Association. Protégete joined forces with the League of Conservation Voters, Chispa activists, Moms Clean Air Force, Juntos and other organizations to demand justice for communities disproportionately affected by asthma and other respiratory illnesses. Pérez Sáez marched alongside a crowd of parents and students, with some kids wearing surgical masks and dressed in yellow school bus costumes.

We should change the narrative of the environmental movement, Pérez Sáez said. “If you want to be an environmentalist, you can be an environmentalist. You don’t need to have the money to buy your own electric car, but we can all advocate to get public transit, to get electric zero-emission school buses. And that will impact everyone at the same level.”

A #Koch-Fueled Attack on #Electric Buses Picks Up Speed #electricvehicles https://t.co/v98YI1cN2U

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) August 24, 2018

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe