Infectious diseases, such as dengue and the Zika virus, could spread to new parts of the world as mosquitoes expand their habitats in a warmer, wetter world, a new study suggests.

By 2061-80, an additional half a billion people could be at risk from diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, the study says—and could even rise to more than 5 billion under a scenario of high population growth.

Predators

There are roughly 3,500 species of mosquito buzzing about on the Earth. One of the most common is the Aedes aegypti.

These blood-sucking insects are canny predators. They are well adapted to urban areas, often lying low under beds and in wardrobes before venturing out in the daytime to seek their prey.

And their preferred prey is, well, you.

The female, which needs the protein in blood to develop its eggs, has acquired something of a taste for humans. They are adept at the “sneak attack”—approaching victims from behind and biting ankles and elbows to avoid being noticed.

Aedes aegypti are “sip feeders,” preferring to take small blood meals from lots of people. This makes them prolific at spreading disease; they are the main carrier of viruses that cause dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya.

Estimates suggest 390 million people a year are infected with dengue and the recent outbreak of the Zika virus in South America has largely been driven by Aedes aegypti.

Currently, approximately 63 percent of the world’s population live in areas where Aedes aegypti are found. The range of these mosquitoes is largely limited by climate—they like the hot, wet conditions of the tropics and subtropics.

However, a new study, published this week in the journal Climatic Change, suggests their habitat could expand as the climate warms—putting millions more people at risk from the viruses they carry.

Suitable Climate

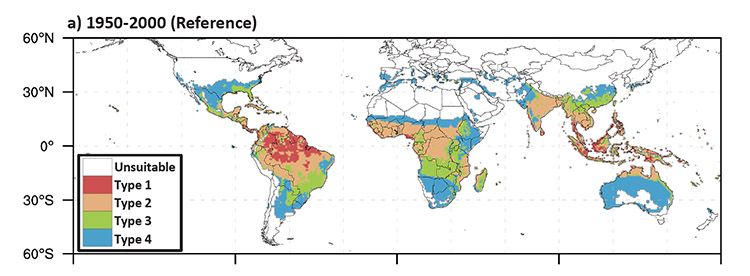

To forecast how the global distribution of the Aedes aegypti might change in future, the researchers first assessed existing habitats across the world. They assigned each area to one of the following four categories of Aedes aegypti abundance, based on the suitability of the climate:

- Type 1: Year-round high abundance (e.g. Manila, Philippines);

- Type 2: Year-round presence, but only seasonal high abundance (e.g. Chiang Mai, Thailand);

- Type 3: Seasonal presence, with eggs surviving through winter (e.g. Buenos Aires, Argentina).

- Type 4: Seasonal presence, but no eggs surviving through winter (e.g., Puebla City, Mexico).

You can see how the different categories are currently spread across the world in the map below. Aedes aegypti are most abundant in the areas shaded red, such as northern South America and much of southeast Asia.

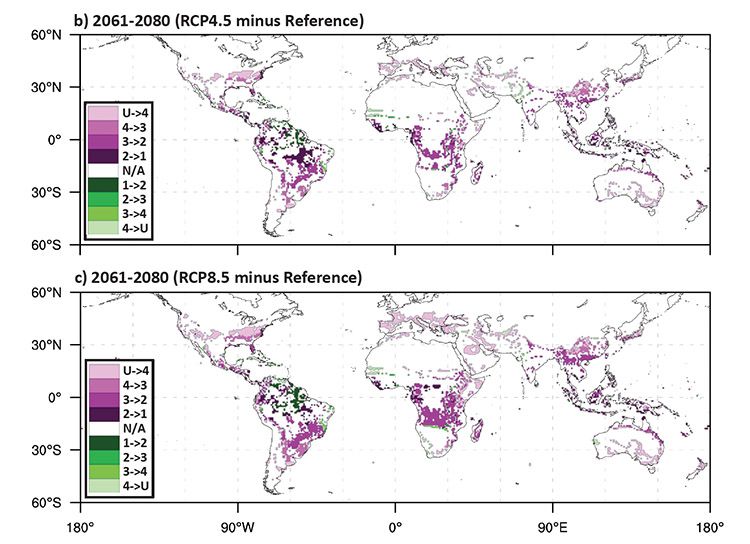

Using projections of temperature and rainfall, the researchers simulated the potential change in global Aedes aegypti habitat by 2061-80. They used two scenarios of climate change—one under moderate greenhouse gas emissions (RCP4.5) and another under high emissions (RCP8.5).

The researchers found the potential habitat range for Aedes aegypti increases by 8 percent under RCP4.5 and by 13 percent under RCP8.5. At today’s population, this translates to between 298 million and 460 million additional people exposed.

The maps below show the changes in habitat projected for the two scenarios. The purple shading indicates areas where the mosquitoes are expected to become more prevalent, while the green shading shows the opposite.

The pale purple shading indicates where the climate is currently unsuitable for Aedes aegypti, but is expected to become suitable on a seasonal basis in the future. Lead author Dr. Andrew Monaghan, a scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, explained to Carbon Brief:

“Under climate change, projected increases in temperatures, in particular, have the potential to allow the mosquito to establish in regions that were previously too cool. These areas tend to be at the margins of present-day survival in mid-latitude regions in North America, Europe, Asia and Australia. They can also be high elevation cities in the tropics and subtropics, such as Mexico City and Quito.”

In much of the tropics and subtropics, the dark purple shading shows where the habitat shifts from being suitable seasonally, to being suitable year-round. This includes much of central Africa, Central America and China.

Projected drier conditions in the Amazon rainforest mean that some areas will become less prevalent for Aedes aegypti in the future (green shading), the study says.

Population Growth

With rising global population, the habitats of Aedes aegypti will also be home to more people in the future.

At present, approximately 3.8 billion people live in areas exposed to these mosquitoes. Accounting for both climate change and population rise, the researchers estimate that this could increase by 2.2-2.5 billion in 2061-80 (based on a global population of around 8.5 billion) or even by 4.8-5.1 billion in a world where global population surpasses 11 billion.

Such a rise in the number of people exposed to Aedes aegypti would have important implications for public health, said Monaghan:

“All else being equal, climate change and population growth will likely increase the percentage of humans exposed to this important virus vector mosquito.”

Cutting greenhouse emissions will “make a dent” in this increase in exposure, said Monaghan, but improving access to clean water and sanitation can also go a long way to reduce breeding grounds for mosquitoes:

“Aedes aegypti strongly depends on humans for its survival—it breeds in human-made containers, such as tires, buckets, barrels, tarps, etc.—and the female virus transmitters prefer to bite humans. We know that areas with better socioeconomic conditions tend to have fewer breeding sites and lower human exposure to the mosquito.”

Studies like this one can help identify where public health actions need to be targeted, said Dr. Paul Parham, a lecturer in public health at the University of Liverpool, who wasn’t involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

“These sorts of maps and analyses are extremely valuable in helping us plan for future novel mosquito-borne outbreaks—and the adverse health effects of the current Zika virus epidemic is a good example of why such advance planning is essential.”

And while increased abundance of Aedes aegypti won’t necessarily translate to a higher risk of mosquito-borne diseases as the world changes, said Parham, it “certainly provides a strong warning” for the future.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Healthy Planet = Healthy People

Scientists Say Arctic Sea Ice Could ‘Shrink to Record Low’ This Summer

New Uncovered Corporate Documents Show #ExxonKnew Much Earlier Than Previously Reported

Why Is This Hormone-Disrupting Pesticide Banned in Europe But Widely Used in the U.S.?

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe