New Online Platform Shows How to Protect Biodiversity and Avoid Ecological Collapse

A new online platform shows where exactly conservation action should be prioritized. ANDREYGUDKOV / Getty Images

By Morgan Erickson-Davis

As the world heads towards 2021 with COVID-19 still raging overhead, it might be easy to forget about the other global crises. But a new app, debuted today, aims to light the way to a brighter future, showing how we can stop global warming, halt extinctions and prevent pandemics – all in one fell swoop.

Research shows that global warming above 1.5 degrees Celsius will likely result in the collapse of ecosystems around the world. Scientists say that not only would this result in mass extinctions, but it would also have dire consequences for humans in terms of food and water security, community resilience against environmental disasters, public health and other societal needs that are intrinsically tied to a healthy environment.

But, according to the numbers, we’re running out of time to do this. Studies indicate that in order to achieve a good likelihood of staying below the 1.5-degree threshold, the majority of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions need to be avoided. Deforestation is one of the biggest emitters of excess CO2 and reducing it is one of the key components to international strategies aimed at mitigating global warming. However, researchers say that if deforestation and other industry emissions continue at current rates, we’ll be on track to reach the 1.5-degree threshold by 2030.

In other words, we have less than 10 years to turn things around.

To this end, a team a team of researchers led by Eric Dinerstein, a wildlife scientist and director at the conservation organization RESOLVE, has created the first comprehensive estimate of the total land area that needs to be protected in order to fix both biodiversity loss and climate change. Called the “Global Safety Net,” the effort combines data on protected areas, intact landscapes, biodiversity importance, and carbon absorption and storage, to show where exactly conservation action should be prioritized. It is visualized on an open-access online platform.

‘Conserve at Least Half and in the Right Places’

The Global Safety Net combines six primary data layers: existing protected areas, habitats where rare species live, areas of high biodiversity, landscapes inhabited by large mammals, large areas of intact wilderness and natural landscapes that can absorb and store the most carbon.

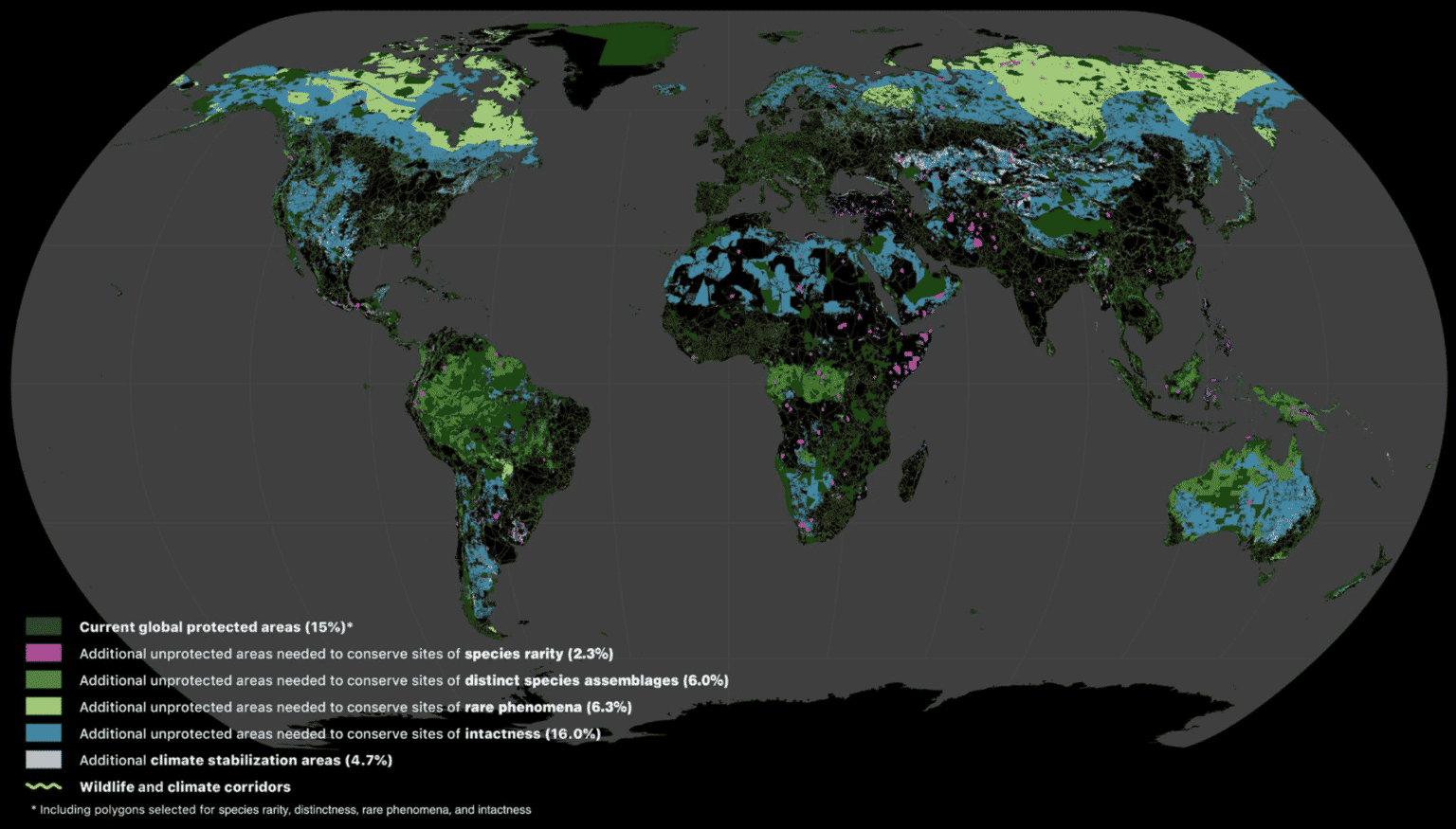

Areas of the terrestrial realm where increased conservation action is needed to protect biodiversity and store carbon. Numbers in parentheses show the percentage of total land area of Earth contributed by each set of layers. Unprotected habitats drawn from the 11 biodiversity data layers underpinning the Global Safety Net augment the current 15.1% protected with an additional 30.6% required to safeguard biodiversity. Additional CSAs add a further 4.7% of the terrestrial realm. Also shown are the wildlife and climate corridors to connect intact habitats (yellow lines). Data are available for interactive viewing at www.globalsafetynet.app. Dinerstein et al., 2020.

In a study accompanying the release of the platform published today in Science Advances, the researchers describe what we need to do in order to stave off the worst effects of global warming and extinction. Overall, they found that in addition to the 15.1% of the world’s land that is already protected, 35.3% will need to be added to fold over the next 10 years. This means that ultimately 50% of the planet’s land area will need to be protected from further degradation to keep it under the 1.5-degree threshold and stave off ecological collapse.

The researchers were surprised how well their numbers lined up with previous estimates of how much of the planet needs to be set aside for nature.

“Without trying, the analysis landed on 50.4% of the terrestrial surface requiring protection,” said study coauthor Karl Burkart, managing director of the NGO One Earth. “Of course conservation is much more nuanced now and strictly protected areas are just one type of land designation that can contribute towards this goal.”

Zooming in, the study finds 30% of land area is of “particular importance for biological diversity.” An additional 20% of land area is needed to maintain ecosystem intactness and provide additional carbon storage and absorption. The authors also note that restoration of degraded areas could help meet carbon sequestration and wildlife conservation goals.

Dinerstein and his colleagues write that the Global Safety Net can be used as a roadmap to achieving climate and biodiversity targets.

“Staying below the 1.5°C limit will require much of the world’s remaining habitat—and a significant amount of restored habitat in forest biomes—be put under some form of conservation by 2030,” the authors say. “Advances being championed under the two conventions responsible for biodiversity and climate— the Convention on Biological Diversity and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change—must be accelerated if we are to protect the abundance and diversity of life on Earth and stabilize the climate.

“A holistic solution is emerging that will accelerate both efforts: conserve at least half and in the right places.”

The researchers identified 50 different ecoregions – areas defined by their unique ecologies and geologies – and 20 countries that hold the lion’s share of conservation potential.

Among them is the Sahelian Acacia Savanna, a vast grassland that stretches across the top of Africa from Senegal to Sudan, the Central Range Papuan Montane Rainforests shared between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, Indonesia’s Sulawesi Montane Rainforests, Madagascar Humid Forests, and Mindanao-Eastern Visayas Rainforests in the Philippines. These areas occupy the top five spots in terms of the amount land that could protected in future, together totaling some 183,000 square kilometers (70,658 square miles) of protection potential and nearly 2% of the planet’s land area.

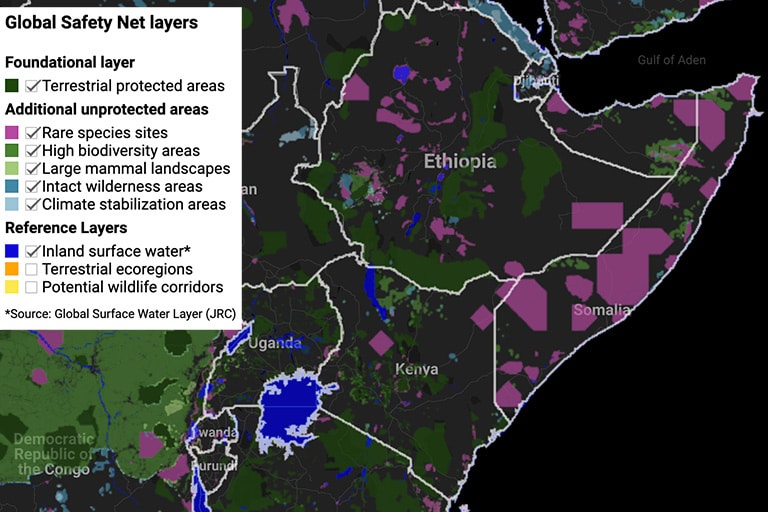

The app also ranks countries on how much of their biological important land areas are under official protection, which is broken down into three lists based on the size of the country. For “large” countries, Nigeria scored the top spot in terms of protection level, Brazil is #15, the U.S. is #34, Indonesia is #47, and Somalia was ranked lowest at #70.

Somalia has large areas inhabited by rare species – but very few protected areas. Global Safety Net

It should be noted that these rankings do not take into consideration deforestation within protected areas. If so, countries like Nigeria and Brazil, where protected areas are increasingly beset by illegal clearing, might not rank so high on the list. Still, the researchers say protected areas provide needed accountability and a metric with which to measure conservation effort.

“Protected Areas (or area-based targets) are certainly no guarantee of conservation outcome, as we can see with the fires burning in Brazil as we speak,” Burkart told Mongabay via email. “But without them we are lost at sea.”

Both Burkart and Dinerstein view area-based targets as the “North Star” of biodiversity preservation and climate protection, and say they are an important part of creating a framework for action that civil society can use to help motivate and mobilize conservation efforts.

“We’ve got to take conservation out of the ivory towers of academic institutions (or basements of government ministries),” Burkart said. “It is the public good we’re talking about, so we need an open and transparent stocktaking of where we are right now, and what we need to immediately prioritize. Area-based targets are just the beginning, a ‘blueprint’ if you will of the cathedral we need to build.”

Will It Happen in Time?

If more than tripling the amount of land under official, effective protection in less than 10 years sounds daunting, you’re not alone. But Dinerstein and his colleagues say it is possible.

One avenue they recommend is safeguarding Indigenous territories. The Global Safety Net shows important conservation areas often overlap with areas occupied by Indigenous communities or regarded as ancestral land, which previous research indicates contain around 80% of the planet’s remaining biodiversity and contribute significantly to carbon storage. Putting land under the management of Indigenous and local communities has been shown to be an effective way to protect it.

“Addressing indigenous land claims, upholding existing land tenure rights, and resourcing programs on indigenous-managed lands could help achieve biodiversity objectives on as much as one-third of the area required by the Global Safety Net,” the researchers write in their study. “Simultaneously, this focus would positively address social justice and human rights concerns.”

Protecting such a large amount of land will take a lot of money. But researchers say that the COVID-19 pandemic is showing just how quickly countries can allocate large amounts of resources if needed. And since research shows deforestation can increase the risk of outbreak of deadly diseases like Ebola and COVID-19, Dinerstein and his colleagues say there is added incentive for funding such efforts.

“The need for an ambitious global conservation agenda has taken on a new urgency in 2020 after the rapid spread of the COVID-19 virus,” they write in their study.

The researchers were surprised to find that only 2.3% of the planet’s land area would needed to be further protected to safeguard the species most at risk of extinction. This, they say, could be accomplished within five years.

Overall, they say the investment spent on preserving these important areas of land would be offset by the trillions of dollars worth of benefits provided by a healthy environment.

“Literally billions of dollars are being spent trying to invent technologies to remove carbon from the atmosphere with very little to show for it. Meanwhile we can protect the spectacular diversity of life on this planet while simultaneously providing all the ecosystem services humanity needs by protecting and conserving the 50% of lands identified in the GSN,” Burkart said. “Based on a new economic analysis, we estimate that the global safety net would cost about 0 [billion per year] to manage. This is a tiny investment for a massive return, as nature provides trillion in ecosystem services every year.”

For their part, Dinerstein, Burkart and their colleagues are continuing to improve the GSN, and are planning on releasing an updated version next year that will include more data layers and higher resolution. They are also developing technology to help monitor elephant populations in the hopes of reducing human-elephant conflict and prevent poaching, as well as a system that detects logging trucks before they get a chance to start cutting down trees.

“Protecting forests begins with early detection and then enforcement,” Dinerstein said. “We think our ForestGuard AI is an important piece of this.”

But the main thing, the researchers say, is that governments must act – and soon.

“Human societies are late in the game to rectify impending climate breakdown, massive biodiversity loss, and, now, prevent pandemics,” they write. “The Global Safety Net, if erected promptly, offers a way for humanity to catch up and rebound.”

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

- Why Biodiversity Loss Hurts Humans as Much as Climate Change ...

- Climate-Driven Biodiversity Loss Will Be Sudden, Study Warns ...

- WWF: 60% of Global Biodiversity Loss Due to Land Cleared for Meat ...

- Scientists Launch ‘Four Steps for Earth’ to Protect Biodiversity - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe