Greenpeace

By Kelly Mitchell

It’s been a big month for news on the state of the U.S. coal industry—from announcements that China is significantly curbing coal use, to the long-awaited unveiling of the Obama Administration’s carbon standards for new coal-fired power plants.

Despite Peabody’s claims that “We have trillions of tons of coal resources in the world. You can expect the world to use them all,” a very different reality is shaping up. ”King Coal” is being reduced to pawn. The open secret is that it has very little to do with new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules.

The beginning of the end.

It’s old news that the coal industry is in trouble. Peabody (BTU) and Arch (ACI), the largest U.S. coal companies, have lost more than 75 percent of their peak value since 2011, as coal struggles to compete with renewable energy and gas. One-hundred-seventy new coal plants representing $450 billion in capital investment have been canceled. Few utility companies are taking a gamble on new coal generation; those who have are in financial trouble. Meanwhile, community activism has worked in tandem with shifting economics to secure the retirement of dozens of existing coal plants. Current and pending federal health and climate rules will only accelerate this trend.

While all eyes were on EPA, a surprising indicator of the severity of coal’s decline emerged from the relatively obscure federal coal leasing program. The Department of Interior (DOI), through its Bureau of Land Management (BLM), owns and manages one of the world’s largest coal reserves in the world in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming and Montana. Since the start of the Obama Administration, DOI has leased over 2 billion tons of federal coal to companies like Peabody, at rates of around $1 per ton. Literally cheaper than dirt.

Not surprisingly, this leasing program has come under intense public scrutiny from environmentalists, taxpayer advocates, U.S. Senators and federal investigators over claims that it is shortchanging taxpayers, ignoring the industry’s desire to export coal overseas, and fueling climate change.

However, recently, BLM is facing a new set of challenges. For the second time in less than a month, federal coal auctions in the Powder River Basin have resulted in no coal sales.

On Aug. 21, Cloud Peak Energy declined to bid for the Maysdorf II coal tract, citing “current market conditions and the uncertainty caused by the current political and regulatory environment towards coal and coal-powered generation.” This marked the first time in Wyoming’s history that a coal lease sale failed to attract a single bidder.

A few weeks later, on Sept. 18, Kiewit mining company placed a 21 cent per ton bid for the Hay Creek II tract—the lowest Wyoming bid in 15 years. BLM rejected the offer. As Ben Jervey at DeSmogBlog put it, “Hey, at least we can’t accuse the BLM of literally giving away coal on public lands.”

Twice, the federal government offered up huge tracts of coal, for what would have been giveaway prices, and the coal industry effectively passed. Coal companies have the whole leasing system rigged in their favor, and it’s still not worth the risk!

But maybe it’s not surprising. The U.S. is moving away from coal in favor of cleaner energy, and the coal mining industry is wary of dumping big money into mines oriented to meet domestic demand. For all the hand-wringing and outrage over EPAs carbon standards for new coal plants, the truth is coal has been behind the curve for some time.

Which brings us to China.

With declining demand at home, the U.S. coal industry has increasingly looked to the export market as its saving grace. Cloud Peak, the company that declined the Maysdorf II tract designed to feed its domestic coal plant serving Cordero Rojo mine, is working to rapidly expand what it calls an “export-focused mine complex” in Montana.

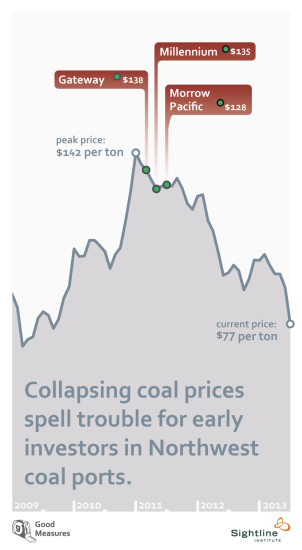

Global coal prices surged in mid 2009, fueled by a large increase in demand for imported coal from China. China’s appetite made coal sales to Asia a lucrative business proposal for companies who could get their rocks on ships, and coal export terminal proposals popped up soon after in Oregon and Washington States. The domestic market was slowing—but, hey, coal companies had a fire exit.

However, it now appears that market has peaked and is on the decline. China’s coal appetite is cooling, and with it the entire Pacific seaborne market. Analysts at Bernstein were blunter:

Globally, Chinese demand growth has been the primary driver or the backstop behind every new investment in coal mining over the last decade. The “global coal market” ended with the collapse in price in 2012.

Ross Macfarlane at Climate Solutions recently posted a brilliant digest of new analysis from Wall St. firms such as Goldman Sachs, Bernstein and Citibank—all pointing to a bleak future for the global coal trade and the U.S. coal industry in particular.

U.S. coal companies are already feeling the impacts of this downturn. Sightline Institute’s recent analysis of Cloud Peak’s second quarter earnings statement revealed that the company made significantly more money betting against coal than it did on actual foreign sales.

And this month, the Chinese government announced a far-reaching air pollution response plan that will lock in additional, long-term declines in Chinese coal consumption—especially in major importing regions.

The plan sets ambitious timelines for reducing fine particulate pollution in Beijing and other key heavily-populated cities. It calls for three main economic areas—Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta—to peak and decline their coal consumption by 2017. It also bans the approval of new conventional coal-fired power plants in these key regions.

The ban on new coal-fired power plants covers China’s most important coal importing regions; the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta, responsible for more than 50 percent of thermal coal imports. It’s hard to read the crystal ball on the long term risks and opportunities in the Pacific coal market, but if U.S. coal companies are hoping for a dramatic surge in new coal demand in Eastern China to restore profitability, they might not want to hold their breath.

The New York Times, Associated Press and Wall Street Journal have reported on these developments with little optimism for the U.S. coal industry, evidenced by headlines like “Coal’s future darkens around the world.”

Cracks in the carbon bubble.

This mix of declining domestic demand and softening coal markets makes the U.S. coal industry the potential bellwether of the coming cracks in the carbon bubble. Peabody’s billions of tons of reserves were scooped up in the promise of growing markets and bigger margins. Now, one word describes the outlook for coal’s economic relevance: smaller.

Analyses from Carbon Tracker have warned that money invested in expanding fossil fuel reserves represent wasted capital as it becomes increasingly clear that most of the world’s fossil fuels are unburnable. Warnings that most fossil fuel reserves cannot be burned have also come from global institutions like the International Energy Agency and, most recently, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report.

Coal reserves are at particular risk of becoming stranded assets for several reasons. As the most polluting fossil fuel, any serious action to reduce carbon pollution must dramatically reduce coal consumption—EPA’s new and pending carbon rules are a clear sign of what’s to come. Further, coal-fired power plants are major sources of deadly air pollution, so efforts to improve air quality are pushing the world’s top coal consumers—China and the U.S.—to rein in coal now.

The U.S. coal industry owns billions of tons of reserves in a developed country that’s steadily retiring coal fired power plants, and their only escape route is a global market that has likely already peaked. Peabody and Arch, the two leading U.S. coal companies, are badly positioned to deal with today’s global markets. Their value is depressed, debt levels are too high and their future sales potential is impaired.

Do not be surprised if the value of these companies, already at record lows, decreases further.

Reporting on major shifts in the domestic and global coal market, the Wall Street Journal recently concluded, “Investors in coal might well feel paranoid. But remember: it isn’t paranoia if the world really is out to get you.”

Down, but not out.

With so much bad news for coal, it might be time to revisit the classic activist narrative of David vs. the Coal Industry Goliath. It may be some time before we see the “end of coal” in a literal sense, but we are approaching a future with fewer, smaller, more volatile coal companies competing for a dwindling share of the electricity market. Coal CEOs should fear irrelevance before death.

But there’s another factor at play—the coal industry has historically punched above its weight, politically. You don’t have to search far to find examples of politicians and regulators green-lighting environmental and financial boondoggles peddled by the U.S. coal industry.

Deutsche Bank may call coal a “dead man walking.” But the industry is still very alive in certain corners of American politics.

DOI continues to hold lease sales, with billions of tons of coal in the leasing pipeline. Obama’s Army Corps of Engineers refuses to look at the full impacts of coal export proposals. Local governments are considering the risks of increased coal dust and diesel pollution because of the promise of economic development, even though that may never come. Members of Congress are introducing countless bills to roll back environmental protections.

Fortunately, these last ditch efforts to secure political support for risky coal projects are being met by a powerful and growing grassroots movement.

China’s ambitious coal reduction plan is a response to growing public demands for clean air. Research shows that every year thousands of Chinese citizens are dying from coal pollution. Those revelations have sowed anger in a Chinese culture that traditionally holds great value on long life, and the ability to enjoy active old age with grandchildren and friends.

Here in the U.S., the heads of more than 20 organizations representing millions of people have called on Interior Secretary Jewell to establish a moratorium on new federal coal leasing. The two failed auctions in the midst of so much controversy should be a wake-up call and opportunity for Jewell to put the brakes on this carbon giveaway. The market is declaring a moratorium; the Secretary must use her policy levers to reshape the program.

And thousands of people are turning out to public hearings, rallies and workshops in opposition to new coal export terminals on the West Coast, joining their voices with small businesses, ranchers, religious leaders and elected officials at all levels of government.

People on both sides of the Pacific are drawing a line against coal, and they will win. Because, in the words of Seattle Times columnist Lance Dickie, “The only return on investment with coal, coal trains and coal terminals is carbon dioxide and ocean acidification.”

The question remains, of course, if we can end our use of coal in time to avoid catastrophic climate change… or if we can draw strength from the victories of the last several years to defeat the Goliaths in the oil and gas industry. But, with a long and difficult fight ahead, we owe it to ourselves to pause and reflect on the successes at hand.

Cheers, to the beginning of the end of coal.

Visit EcoWatch’s COAL page for more related news on this topic.

——–

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe