Ice Shelf Holding Pine Island Glacier Could Collapse Within a Decade

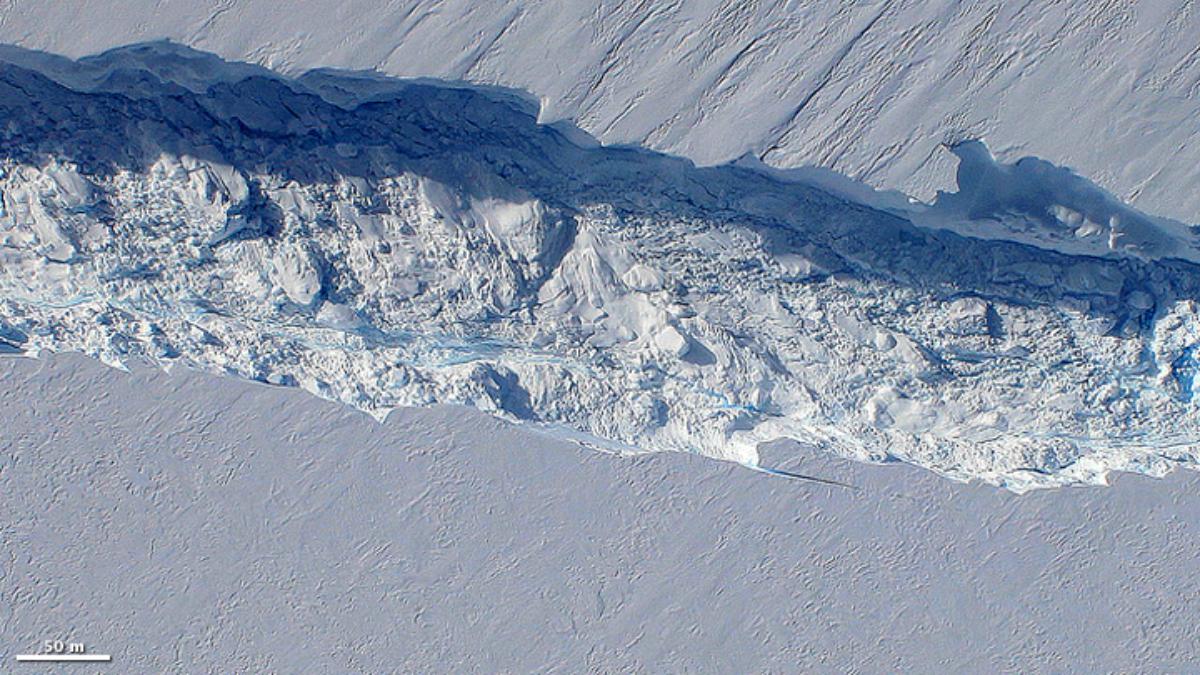

A crack in the Pine Island Glacier. NASA's Earth Observatory / CC BY 2.0

The Pine Island Glacier is currently Antarctica‘s greatest contributor to sea level rise, and, now, a new study warns that it could be closer to collapse than previously thought.

The research, published in Science Advances Friday, found that the vulnerable glacier had sped up by 12 percent over the last three years as the ice shelf holding it in place breaks up. This finding could accelerate the timeline for when the entire glacier collapses into the sea, and underscores the urgency of acting to combat the climate crisis.

“These science results continue to highlight the vulnerability of Antarctica, a major reservoir for potential sea level rise,” Twila Moon, a National Snow and Ice Data scientist who wasn’t part of the research, told The AP. “Again and again, other research has confirmed how Antarctica evolves in the future will depend on human greenhouse gas emissions.”

The Pine Island Glacier is one of two Antarctic glaciers that most concerns scientists. It and the Thwaites Glacier sit side-by-side in western Antarctica, and keep the rest of the region’s ice in check.

If they both collapsed, global sea levels would rise by several feet within a few centuries, a University of Washington (UW) press release explained. The Pine Island Glacier on its own contains enough ice to bump sea levels up by 1.6 feet if it melted. And it is already having an impact. It raises sea levels by a sixth of a millimeter each year and, according to The AP, accounts for about 25 percent of Antarctica’s total ice loss.

But the glacier is kept from retreating further by its ice shelf, which acts like a flying buttress on a cathedral, containing its mass, the press release explained. That is why Friday’s study is concerning. It analyzed satellite images to show that the ice shelf lost a fifth of its area between 2017 and 2020, and retreated by 19 kilometers (approximately 12 miles) during that time, the study authors wrote.

The images, recorded by the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellites, were taken every 12 days between 2015 and 2017, and every six days between 2017 and the present. They revealed that the ice shelf lost most of its mass in three big breakages, calving icebergs more than five miles long by 22 miles wide, according to The AP.

The study also looked at the relationship between the breakup of the ice shelf and the retreat of the glacier, and found that the glacier’s movements were directly related to the ice shelf’s deterioration.

“The recent changes in speed are not due to melt-driven thinning; instead they’re due to the loss of the outer part of the ice shelf,” study lead author and UW glaciologist Ian Joughin said in the press release.

All of this means that the shelf and the glacier could both collapse much sooner than previously anticipated.

“It’s not at all inconceivable to say the rest of the ice shelf could be gone in a decade,” Joughin told The Washington Post. “It’s a long shot. But it’s not that big a long shot.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe