17 States Investigate Dicamba Damage Complaints Spanning 2.5 Million Acres

Complaints of crop damage from the powerful and volatile weedkiller

dicamba have increased rapidly around the country.

According to weed scientist and University of Missouri associate professor Kevin Bradley, 17 state governments are investigating more than 1,400 official complaints of dicamba-related injuries this year covering 2.5 million acres.

“This is a substantial problem that needs to be addressed,” Bradley wrote.

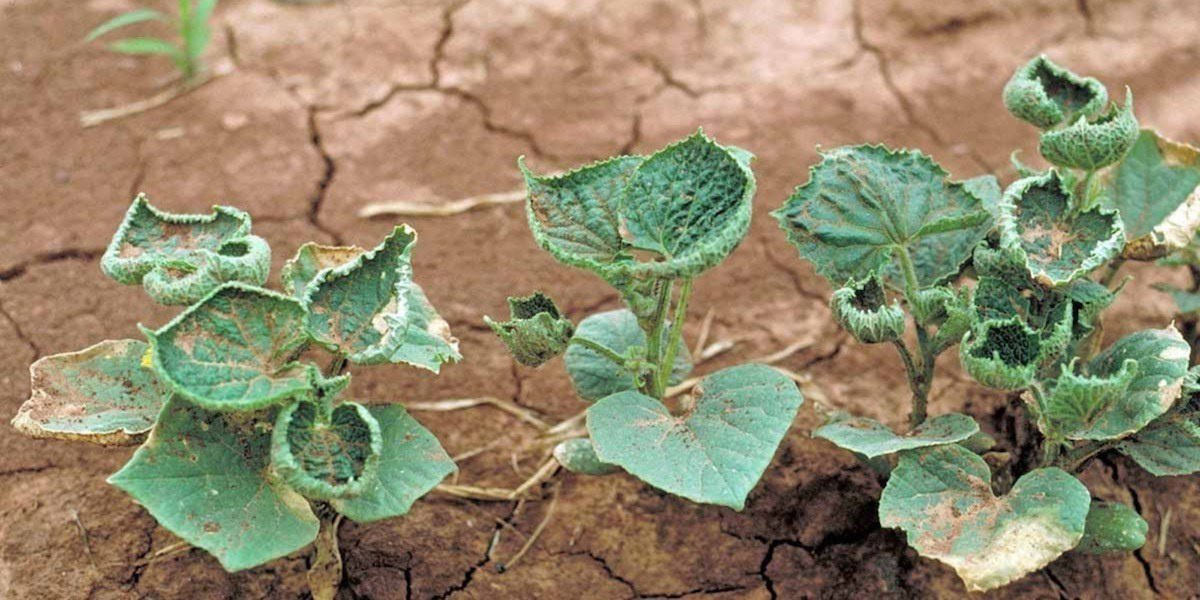

Reports suggest that farmers applied the herbicide to Monsanto Co.’s new dicamba-tolerant soybean and cotton crops to beat back ever-resistant weeds, but the drift-prone chemical can be picked up by the wind and land on neighboring non-target fields, crops and native plants. Fruits and vegetables, as well as other crops that are not genetically engineered to withstand dicamba, are often left cupped and distorted when exposed to the chemical.

The current rash of complaints echoes the similar devastation last summer, when 10 states reported hundreds of thousands of crop acres adversely impacted by the apparent misuse of the herbicide.

Although dicamba has been around for decades, Monsanto, DuPont Co. and BASF SE sells new formulations of the herbicide that’s said to be less drift-prone and volatile than older versions when used correctly.

Monsanto execs defended its product, blaming growers for using older versions of dicamba or not following directions on the new product label. As reported by Bloomberg:

The company attributes the drifting problem to farmers using illegal, off-label products that are more volatile—and thus more prone to drift—than the latest versions of dicamba. They may also be cleaning or using their spraying equipment incorrectly, or applying dicamba when it’s windy, said Robb Fraley, executive vice president and chief technology officer.

But Bradley, University of Missouri’s weed scientist, casted off what he considers as industry excuses:

First, does 1,411 official dicamba-related injury investigations and/or approximately 2.5 million acres of dicamba-injured soybean constitute a problem for U.S. agriculture? I guess it depends on your perspective but my answer is an emphatic yes. If you think so as well, let others know how you feel and let’s stop the standard denial routine that I have heard so often this season. Instead, lets put our time and effort into figuring out where we go from here as an industry and what’s going to be different about next season.

Second, I said previously that the purpose of this article is NOT to debate about the reasons for off target movement. And it isn’t. And I’m not. But the reasons for off-target movement of dicamba are the number one thing we are going to have to discuss if you agree that there is a problem. So my last question is this; can you look at the scale and the magnitude of the problem on these maps and really believe that all of this can collectively be explained by some combination of physical drift, sprayer error, failure to follow guidelines, temperature inversions, generic dicamba usage, contaminated glufosinate products, and improper sprayer clean out, but that volatility is not also a factor?

I know what my perspective is, what’s yours?

In recent months, states such as Arkansas, Tennessee and Missouri—Monsanto’s home state—have imposed temporary bans or restrictions on the use of dicamba to curb further damage. Farmers in several states have filed lawsuits against BASF, DuPont and Monsanto over damages.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is now reviewing its directions on how to use the new formulations following the crop damage reports.

“We are reviewing the current use restrictions on the labels for these dicamba formulations in light of the incidents that have been reported this year,” agency spokeswoman Amy Graham told Reuters.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe