How Do These Fireflies Sync Their Iconic Flashes? New Research Has Answers

The synchronous display of the Photinus carolinus firefly is so mesmerizing that it draws more than 12,000 visitors a year to one of the species’ chief staging grounds in the Elkmont, Tennessee section of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. But despite the event’s popularity, many questions remain about how and why the fireflies are able to choreograph their light show.

To help shine some light, a trio of researchers from the University of Colorado used 360-degree video recordings and three-dimensional reconstructions to “quantif[y] and characterize precisely” key aspects of the fireflies’ behavior for the first time, as lead author Raphaël Sarfati told EcoWatch.

“There’s a couple of results in the paper that we think draw a broader picture of how fireflies communicate and interact when they are in their natural environment,” he said.

Waves of Light

The first major finding documented in the study, which was published in Science Advances July 7, is that the fireflies only begin to synchronize once they reach a certain density.

In the wild, the researchers can’t determine exactly what number of beetles per cubic meter are required to start the show, because the fireflies are hidden in dense vegetation and the cameras cannot record all of the insects at once. However, in a study published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface last year, the same team found that male Photinus carolinus fireflies will begin synchronizing their flashes when 15 or more are grouped in the lab. The latest study confirms that density and synchronicity go hand in hand in nature as well.

A stacked image of Photinus carolinus at the Smokey Mountains. Peleg Lab at CU Boulder

The second major finding involves how the fireflies synchronize their blinkings despite being separated from each other by vegetation. On the ground observations had pointed out that the synchronization tended to take the form of a wave, but observers were not exactly sure how this was happening.

The researchers discovered that the insects were copying their nearest neighbors using visual cues in order to create the wave effect.

“What we found is that the wave is not occurring because fireflies are moving together with the wave front,” coauthor Orit Peleg explained. “They’re actually different fireflies that are being triggered by their neighbors.”

The team discovered their findings by recording the fireflies for two weeks in the early summer of 2020, from June 3 — at the very beginning of firefly activity — to June 13, four nights into the peak of their display. They placed two cameras facing the fireflies, positioned to overlap. They also placed two cameras in the vegetation, about two to three feet from the ground where the fireflies are normally positioned.

“When you record from this perspective you’re really watching from the inside,” Sarfati said.

They used the recordings to reconstruct a three-dimensional cone of the fireflies’ display, allowing them to understand mathematically how the wave was propagating and how quickly, as well as how the fireflies’ behavior changed when their numbers increased.

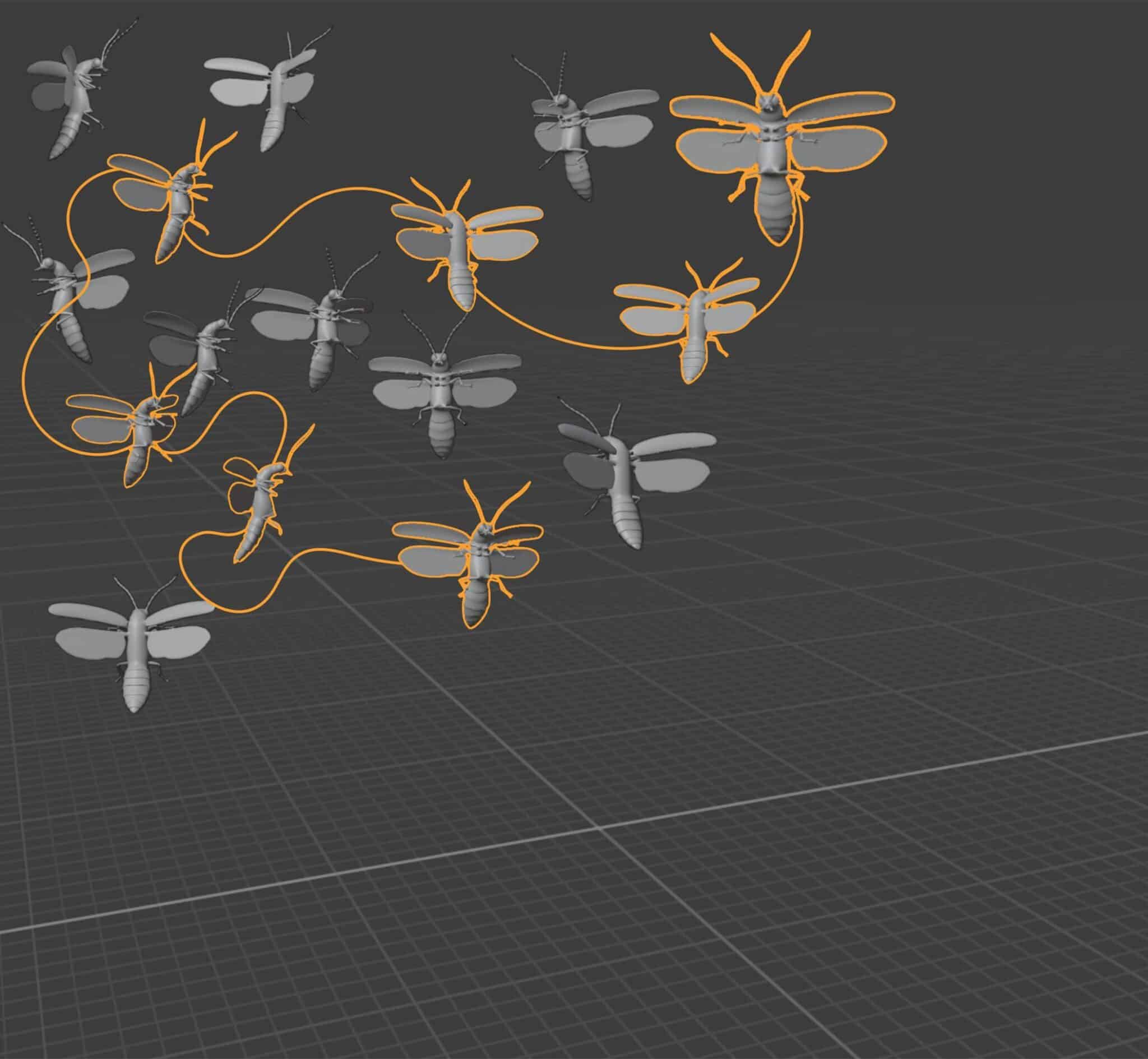

Abstract illustration of tracking individual fireflies. Peleg Lab at CU Boulder

Their results have earned the respect of other firefly experts. Lynn Faust, author of Fireflies, Glow-worms and Lightning Bugs and the woman who first alerted the scientific community to the synchronous display at Elkmont, praised the team and their research.

“[I]t is really fascinating to see actual hard data, numbers and charts illustrating what I have observed (and enjoyed) for most of my 66 years of life,” she told EcoWatch in an email.

She was especially impressed with a chart showing how the population of blinking insects nearly doubles each night as the peak of the display approaches, something she had observed but never seen quantified.

“This team has done a wonderful job and like all good studies, even more questions arise with each question answered,” she said.

Mysteries Remain

Sarfati and Peleg also acknowledge that there is still much scientists don’t know about firefly synchronization. For one thing, they are still not entirely sure why fireflies do it. It is clearly part of their mating process, but the jury is out as to why. One theory is that the males’ synchronized flashing allows females to see them from farther away. Another is that it helps the insects to better distinguish male from female flashes.

Furthermore, scientists are hoping to understand how insights into Photinus carolinus synchronization could apply to other species and fields. Peleg and Sarfati themselves are working on comparing their findings to the displays of Photuris frontalis, the other species of synchronous firefly in the U.S.

However, Peleg noted that synchronization occurs throughout the field of biology, from schools of fish to heart cells that synchronize to pump blood and neurons whose synchronization can cause problems such as epilepsy.

“[W]e hope that the results we found with fireflies could also be projected to these seemingly very different systems,” she said.

This extends beyond the field of biology altogether. Peleg said the research had generated interest in the field of swarm robotics, in which scientists are hoping to train many smaller robots to coordinate their behavior.

For their part, Peleg and Sarfati’s next research will involve working in the lab to understand how an individual firefly perceives stimuli in its environment and decides to flash.

“That’s the holy grail,” Sarfati said. But he acknowledged that part of the fun was having some knowledge just out of reach.

“It’s nice to keep a little bit of mystery and excitement around fireflies,” he said.

Lights Out?

As researchers work to understand the secret of the fireflies’ flash, some of them are blinking out forever.

Photinus carolinus themselves are considered a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. Faust noted that the species is relatively protected. The famous Elkmont population lives within a national park, and most other large populations of the species exist in national, state or private conservation areas. However, she noted that the species, and their displays, might have once been more prominent outside of protected land.

What Photinus carolinus does have to contend with is its own fame. Faust called firefly tourism a “double-edged sword.” While it increases awareness of and respect for fireflies, it also presents threats in the form of so many people intruding on their habitat. In a first-of-its-kind study of firefly tourism published in Conservation Science and Practice this March, Faust and a team of international researchers documented these concerns, such as trampling, habitat degradation to build tourist infrastructure, and light pollution, but also provided guidelines for sustainable firefly tourism practices.

In general, experts have observed a decline in firefly populations around the world and attributed the main causes to habitat loss, light pollution and pesticide use, according to a 2020 study. Faust noted that the insects are most vulnerable not during their famous displays, but during their larval and pupal stages. For fireflies in the Southern U.S., this stage lasts nearly a year, while they only live as blinking adults for two to four weeks.

“We can lose entire populations and never even know it when we clear an old woodlot or farm for a subdivision,” she said. “The next generation is hidden down in the soil but will never make it to adulthood when their soil is moved, their habitat obliterated — but we humans will never see that. We will only notice the next year that ‘this place has no lightning bugs anymore, no fireflies.'”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe