Anishinaabe Tribes in the Northern U.S. Are Adapting to Climate Change

Anishinaabe tribes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan are adapting to climate change in the Northwoods (pictured) by prioritizing relationship-building and observation of the land. Matthew Crowley Photography / Getty Images

By Samantha Harrington

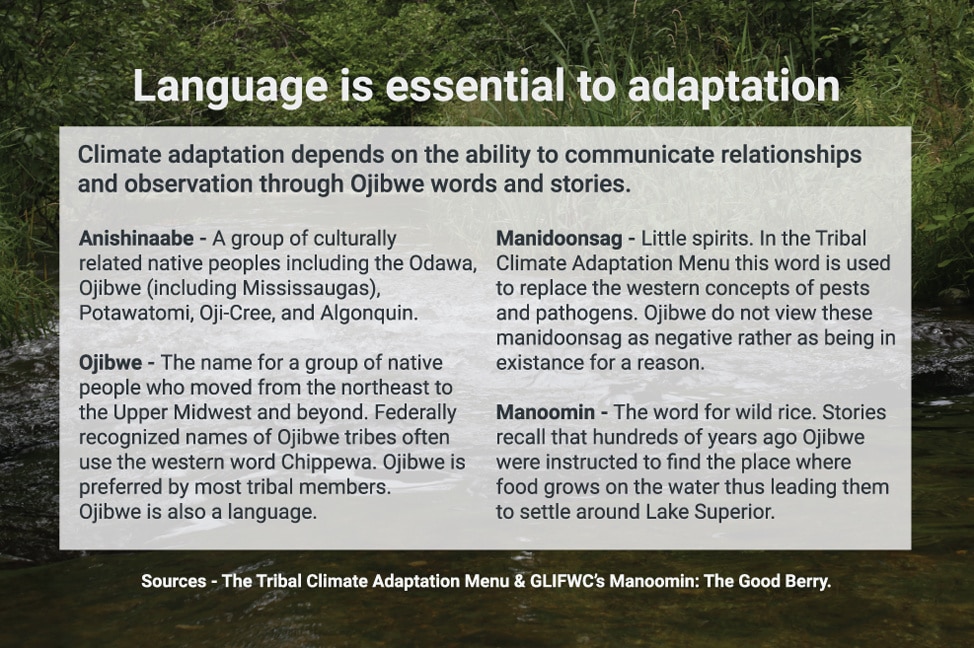

If the forests of northern Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan keep secrets, it’s only because people fail to listen. For about 500 years, since they moved to the region from the Northeastern U.S. and Canada, Anishinaabe tribes have built relationships and history with all beings in the region – from tall trees and moose to grains of sand and manidoonsag, which means “little spirits” in Ojibwe. Elders and tribal members who have taken the time to observe the landscape have witnessed their community members, both human and otherwise, adapt to harsh winters, wildfires, storms, pest outbreaks, and the arrival of Europeans.

Now they are recognizing the impacts of climate change on their communities. They can taste it in the way that the flavor of beaver worsens sooner as springs warm up earlier in the calendar year. They have heard it in the way the wind blows through declining beds of manoomin, or wild rice. There have been more obvious changes, too. Intense storms have washed out bridges and eroded the shores of small lakes and Lake Superior.

Despite limited financial resources, tribes in the region have prioritized a holistic kind of climate adaptation that is rooted in traditional values of relationship-building and observation. By taking their time, tribes have been proactive while striving to adapt in a way that aligns with their values and that is conscious of a scope and timescale much larger than one human life. As tribes do this work, they come up against the limitations of operating within a cultural system in the U.S. that is often diametrically opposed to the Anishinaabe worldview.

Leading on Climate Change

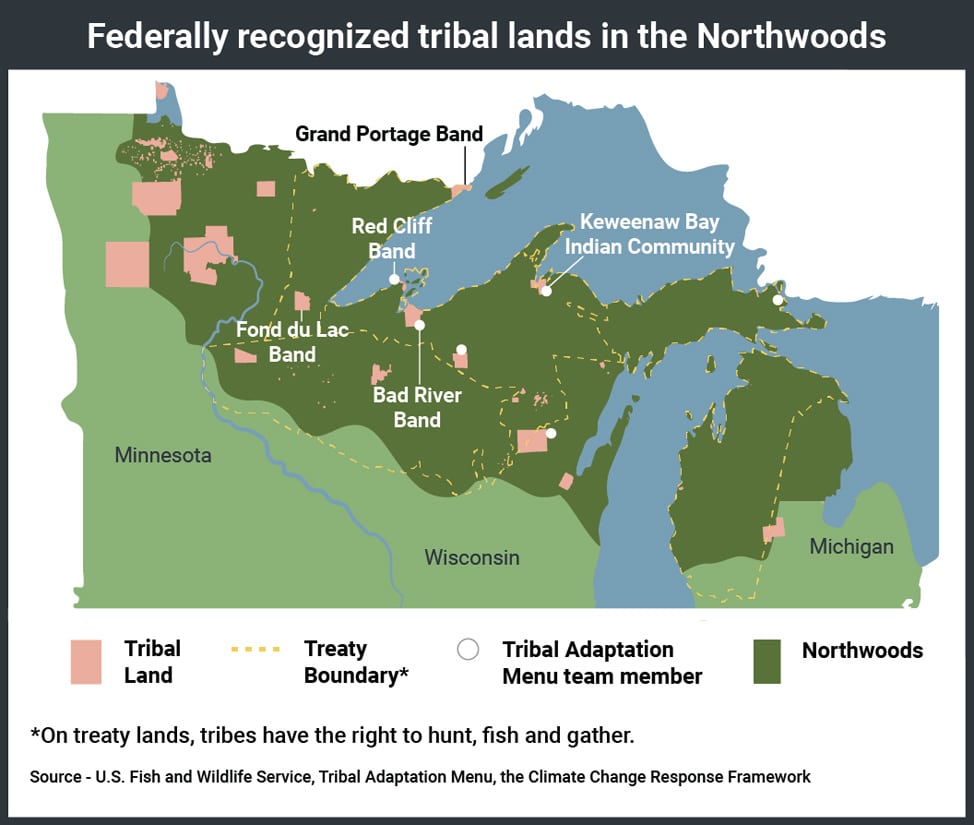

In 2007, Wayne Dupuis, the environmental program manager of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, approached the tribal council about adding the goals of the Kyoto Protocol into the tribe’s resource management planning. They agreed. A year later, the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, in far northeastern Minnesota, was the second tribe in the U.S. to begin an adaptation plan. The majority of tribes in the region have since created or begun climate change monitoring and adaptation work.

Those timelines outpace many non-tribal communities in the Upper Midwest. The politically progressive county that houses Wisconsin’s state capital did not create its Office of Energy and Climate Change until 2017.

Fifteen years ago in Grand Portage, the tribe began to notice and study the decline of brook trout in Trout Lake, a 61-acre lake on the reservation. Eventually the lake warmed so much that temperature-sensitive trout could no longer survive. The tribe restocked the lake with walleye and yellow perch, which thrive in warmer water. But Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources has not taken similar measures in other lakes in the northern part of the state.

“I think we’re going to see a massive loss of trout species in northeastern Minnesota, and I think that the Minnesota DNR is going to have to really consider: Is it acceptable to have a whole bunch of lakes with no fish, or do we start trying to change to fish communities that are a bit more resilient?” asked Seth Moore, the director of biology and environment at the Grand Portage Band. “That’s a no-brainer in my opinion. It almost feels like they’re a decade late.”

A Close Relationship With the Land

The guiding force behind much of this early work is the Anishinaabe emphasis on the connectedness of all beings and actions.

“We are here because of our relationship with the land,” Dupuis said. “In many of our stories, it’s our relationship with the Earth and the animals, the swimmers, the flyers that needs to be in harmony, and if we skew that balance, bad things happen. So our relationship with the Earth is primary – to be aware of what we’re doing and considerate in what we do.”

Katy Bresette, a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe and an Ojibwe educator, said that it’s important not to romanticize this practice as something mystical and far removed from a process that everyone is capable of. Looking at adaptation from the perspective of all members of the ecosystem and the connections between them helps create solutions that look beyond an individual human life.

“You have to understand that it’s not necessarily about understanding whether changes are coming sooner,” Bresette said. “It’s just understanding that the changes exist and what they look like.”

Ojibwe lands are particularly vulnerable to warming temperatures. The Northwoods lie in a transition zone between southern forests and the boreal forests of the north. Many of the region’s cold-loving species, like paper birch and moose, are living in the southernmost reaches of their range. Warmer winters have already prompted the decline of some cold-weather species and the northerly migration of new species that were once killed off by the cold.

In addition to their inherent value as beings, many vulnerable species are culturally significant for their direct roles in tribal ceremonies and subsistence. Ash trees, threatened as warmer temperatures allow emerald ash borer to gain a stronger foothold in the forests, have long been used to make baskets, fishing tools, pipe stems, and lacrosse sticks.

Alex Mehne, forest manager of the Fond du Lac Band, said that black ash trees – which are the dominant tree species in the area – are critical in maintaining water levels in wetlands. Black ash trees grow in large groups in forested wetlands, where they absorb water from the ground.

That process helps protect critical manoomin beds downstream, particularly as rainstorms get more intense. Manoomin is sensitive to water changes, especially in June and July. “If the water level goes too high the plant will drown, and if it goes too low it’ll be destroyed,” said Eric Andrews, climate change coordinator of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

After an intense storm in 2012, the Fond du Lac manoomin crop failed.

As they noticed these vulnerabilities, Anishinaabe people began work to ease the coming changes. The Fond du Lac Band is experimenting with planting alternative wetland tree species to see if they could play a similar role in the ecosystem to the ash trees. So far, swamp white oak and silver maple seem to be succeeding.

Documenting Tribal Adaptation Strategies

Tribal adaptation in the Northwoods depends upon collaborative relationships between tribes and other regional resource managers. Those relationships were essential in the creation of the 2019 Tribal Climate Adaptation Menu (TAM), a document that includes 14 different adaptation strategies that can be used to help guide climate planning. It was born from an inclusive, community-centered process that contrasts with Western-style approaches in the region.

The menu came into being after some tribal members were involved in a watershed adaptation workshop put on by the Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science. The institute, which is a partnership of federal agencies, universities and conservation organizations, has developed a variety of “menus” that present climate change adaptation strategy options for forest managers. At the watershed menu workshop, tribal members realized that while the process was useful, it was missing important context for tribal planning, such as shared values and community engagement.

“Eventually it came out that we needed a whole separate menu,” said Nisogaabo Ikwe Melonee Montano, a member of the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe and the traditional ecological knowledge outreach specialist at the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

An essential part of creating this menu was establishing deep relationships and trust among the 19 creators of the document, who included both tribal and non-tribal members.

“Early on we kind of started joking with each other that it was actually the TAM fam,” Bresette said. “There has been reciprocity here, and there has been love for each other.”

All decisions about what to include in the menu were made by consensus. The menu’s stated values are specific to the Great Lakes Anishinaabe perspective, but it is intended to be a living document that helps other tribes and non-tribal communities create plans for managing the impacts of climate change.

Nikki Cooley, of the Diné (Navajo) Nation, manages the Tribal Climate Change Program at the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals at Northern Arizona University. She said that there has been a lot of interest in expanding the menu to include values and languages from other tribes.

“In all my time, whether it’s been in Glennallen, Alaska, which is a super small town four hours from Anchorage, or on the shores of La Jolla beach in San Diego, the commonality is that tribes are always very concerned about how climate change is going to affect their culture,” Cooley said.

Members of the TAM team emphasized that people should spend time observing the environment before implementing any of the strategies so that they can make decisions informed by elders and non-human members of the community.

“They’re giving us the things that we need to know and understand,” Bresette said. “We’re the only ones who aren’t in the classroom. We’re the ones who aren’t spending time on our lessons. We’re the ones not doing our homework.”

Caught Between Conflicting Cultural Values

The TAM process centered native voices, but that is not always the case, even in tribal projects. Additionally, choices made by neighboring landowners can complicate work that tribes are doing.

Climate program leaders and resource managers at Red Cliff, Bad River, and Fond du Lac noted how much time they spend trying to prevent resource extraction companies from damaging their environment.

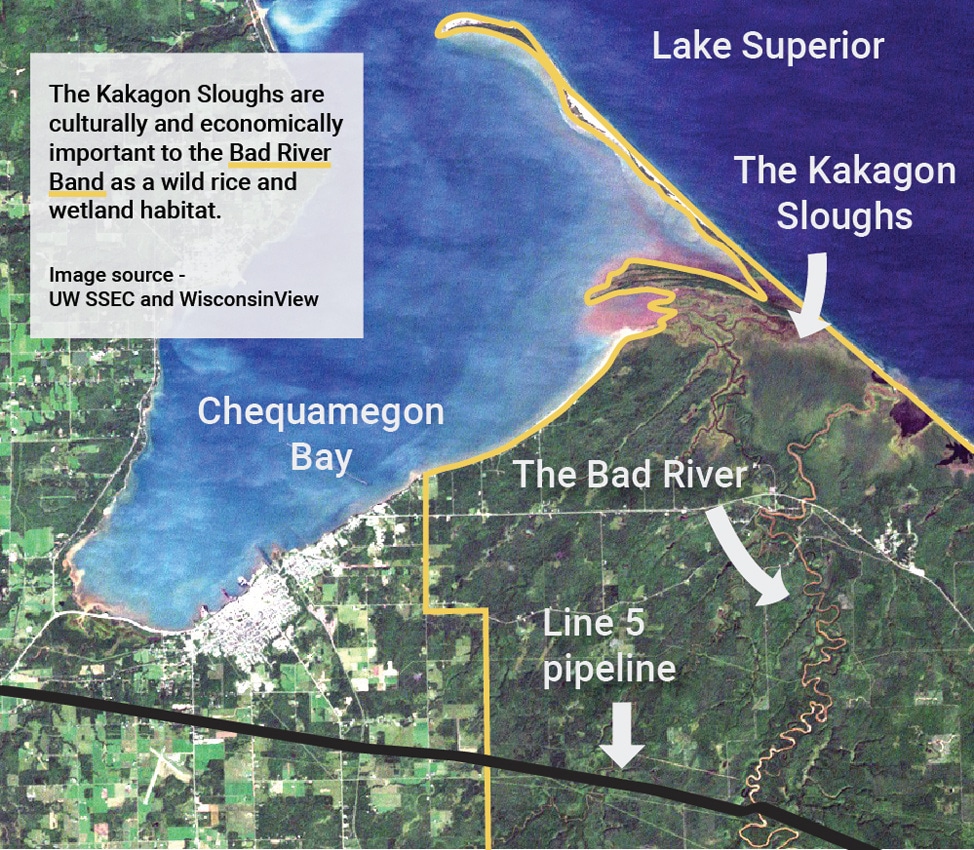

Andrews at Bad River is particularly concerned about the Line 5 natural gas and oil pipeline, operated by Enbridge, a Canadian energy company. The Bad River is eroding where it crosses the pipeline, particularly as heavy rainstorms become more frequent. The erosion is expected to expose the pipeline and put it at increased risk of breaking – worrisome as downstream of the intersection of the river and pipeline are the Kakagon Sloughs, a protected wetland and wild rice bed. It is a critical resource for the tribe.

Gidigaa-bizhiw (Jerry Jondreau), a member of the TAM team from the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community who founded his tribe’s forestry department, said that the practice of prioritizing the use of natural resources for financial gain over the health of the whole ecological community is incredibly frustrating. “We’re fighting with a system that is essentially backwards,” Gidigaa-bizhiw (Jondreau) said. “It’s designed from that Western viewpoint.”

Gidigaa-bizhiw (Jondreau), said that he often found himself the only indigenous voice in the room in forestry conversations. He said that traditional knowledge was often brushed off and that native voices need to be, at minimum, equally represented in order to be heard. Native communities, he said, have been doing the work of caring for the environment for millennia and that people with resources need to recognize that expertise and support it.

“Relinquish authority,” Gidigaa-bizhiw (Jondreau) said. “If you have money, and you want it to go to a good place, then give it to the people that are doing this work and don’t make them jump through 10,000 hoops to try to get this stuff, because then you spend all your time working on the damn grants and not doing the work.”

The Northern Institute of Applied Climate Science demonstrated support for elevating the expertise of native communities in the Upper Midwest in their commitment to developing the TAM. And some in Wisconsin’s state government express interest in doing the same. “We owe it to the first stewards of this land to listen to them, partner with them, and follow their lead in making Wisconsin a more sustainable and equitable place for everyone,” Wisconsin Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes said via email.

Reginald DeFoe, the director of resource management for the Fond du Lac Band in Minnesota, remains deeply worried about the lack of leadership on climate action in the U.S. and the world.

“I think the only way out of this kind of mess is we can’t look backwards and blame everyone for what happened. The only way is to look forward,” DeFoe said. “But right now the leadership is on a different track; they want to exploit more resources – mining, oil – and it just goes on and on.”

Reposted with permission from Yale Climate Connections.

- Indigenous Solutions to Climate Crisis Could Lie in Archaeology ...

- 'Historic Moment' for Indigenous People at Climate Talks, New ...

- Why Defending Indigenous Rights Is Integral to Fighting Climate ...

- Countries Must Adapt to Climate Change Now, UN Warns - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe