By Marlene Cimons

Cristina Stinson never had an allergic reaction to ragweed until after she started working with it. “I think the repeated exposure to the pollen is what did it,” she said. It also didn’t help that her community is chock-full of it. “There is plenty of ragweed in my neighborhood,” she said. “In fact, it grows right outside my door.”

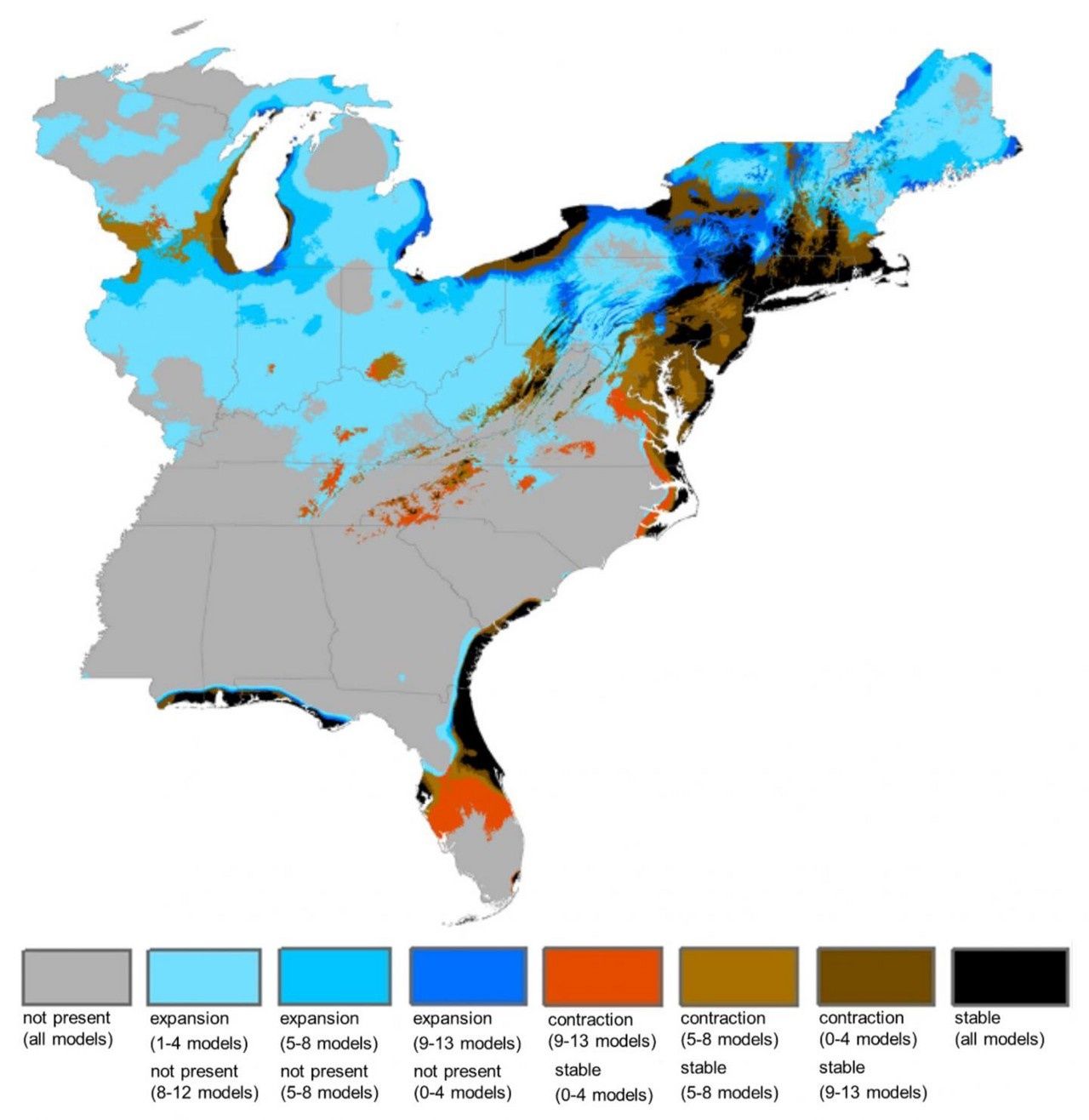

Stinson, assistant professor of plant ecology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a ragweed expert, knows that ragweed allergies, as bad as they are now, are going to get worse because of climate change. New research she conducted with Michael Case, a postdoctoral researcher in landscape ecology and conservation at the University of Washington, suggests that the plant will migrate north in the next three and a half decades. It will sprout where it hasn’t been before, and proliferate where it already is.

Upstate New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine, where ragweed has not been documented, will be especially vulnerable, according to their study. The study appears in the journal PLOS ONE, and is believed to be the first to examine ragweed distribution in the U.S.

Nexus Media

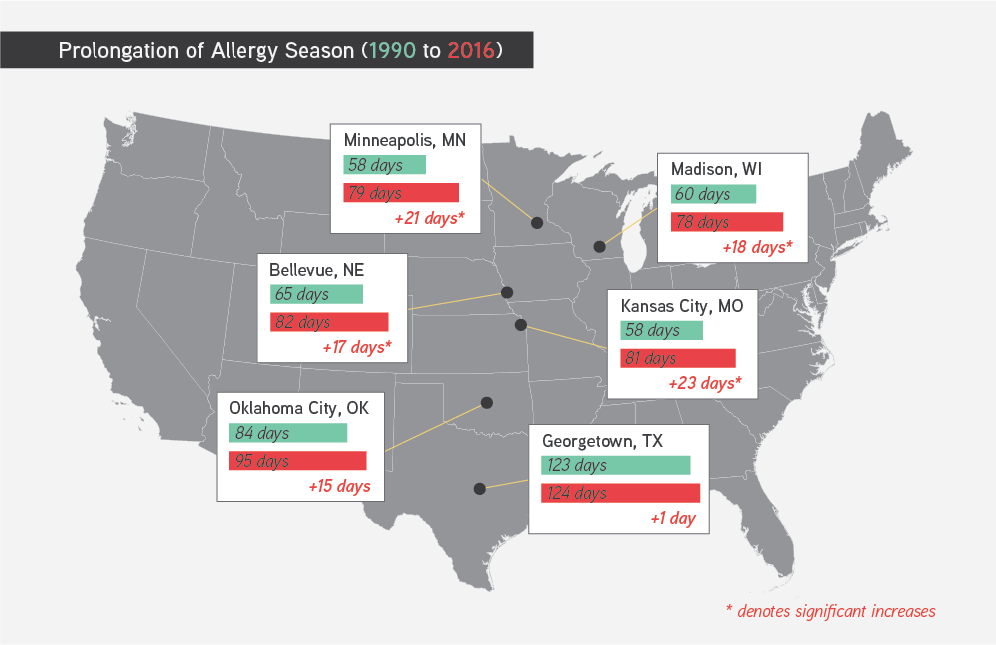

Moreover, the effects of climate change also could result in a longer ragweed season, which currently begins in August and lasts through November.

“Ragweed is already flowering earlier and longer than it has in the past, so if the climate conditions become conducive, it is possible that the pollen season could start sooner and end later,” Stinson said. “Historical pollen records tell us that ragweed thrives in hot, dry environments. When we grow ragweed at high CO2 it luxuriates and produces more pollen.”

Increasing amounts of fine-powder ragweed pollen, the primary allergen for hay fever symptoms, will mean increased misery in the form of sneezing, runny noses, irritated eyes, itchy throats and headaches. “One reason we chose to study ragweed is because of its human health implications,” Stinson said. “It affects a lot of people.”

The warming climate has brought early springs, late-ending falls, warmer and shorter winters and large amounts of rain and snow. All of that, combined with historically high levels of carbon dioxide in the air, nourishes all of the trees and plants that make pollen, not just ragweed, as well as promoting fungal growth, such as mold, and the release of spores, other sources of allergies.

“Many plants increase reproduction with warmer conditions, so it’s possible that plants other than ragweed also will produce more pollen under future climate scenarios,” Stinson said. “If that pollen is also allergenic, there could be a compounding effect of climate change on allergies.”

Allergies occur when the body’s immune system overreacts to a substance that generally doesn’t bother other people. Allergies are the sixth leading cause of chronic disease in the U.S., with an annual cost of more than $18 billion, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 50 million Americans suffer from allergies annually. Some are merely annoying—symptoms from ragweed exposure, for example—but others can be life-threatening, such as a bee sting, or a reaction that provokes an asthma attack.

Most experts believe the impact of climate change on allergic diseases will vary by region, depending on latitude, altitude, rainfall and storms, land-use patterns, urbanization, transportation and energy production. Drought, for example, will contribute to increased air pollution—exacerbating asthma and other disorders—while heavy rain will wash the pollution away, but encourage the growth of mold.

The study also found that locations where ragweed now is widespread may see less of it in the coming years because of changing conditions and climate variability. These include places like the southern Appalachian Mountains, central Florida and northeastern Virginia. “Ragweed is projected to decline in some areas because it may not be climatically suitable in the future, meaning that the climate will be too wet or dry or hot or cold for it,” Case said. “Maybe that is the silver lining, that there are some opportunities for those communities to actually get some headway on mitigating or even eradicating this species.”

Ragweed expansion projection by the 2050s, under a high-emissions scenario. PLOS ONE

To get their projections, the scientists built a machine learning model using Maxent software that draws upon some 726 observations of common ragweed in the eastern U.S. taken from an international biodiversity database. They then combined them with climate information in order to pinpoint specific conditions that encourage ragweed to flourish. The authors ran their models into the future, using temperature and precipitation data from 13 global climate models under two different potential scenarios for greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition to ragweed’s northward expansion, the models also showed that—while ragweed would surge overall in the eastern United States by the 2050s—it would then be followed by a slight contraction between the 2050s and the 2070s, as temperature and precipitation become more variable. “We don’t know for sure if the climate will become more variable by the end of the century but the climate models that we used for this study indicate that,” Case said. “It is kind of an interesting case study of climate change effects: It’s not all bad, it’s not all good,” Case said.

Although the results generally don’t bode well for hay fever sufferers, the researchers said communities could use the information to prepare for what was ahead. “Weed control boards, for example, might include ragweed on their list to keep an eye out and monitor for,” Case said. “Historically they might not have been looking for ragweed, but our study suggests maybe they should start looking for it.” (Weed control boards are committees set up by state or local governments to monitor weeds in communities, and decide what to do about them.)

The study covers only the area east of the Mississippi River, largely because those regions provide more than enough ragweed for observation, and to run the models, the scientists said. The plant is commonly found in Illinois, Florida and the eastern seaboard from Washington, DC to Rhode Island. It is possible that ragweed also could expand westward or north into Canada, Case said, but those areas were not included in the research.

“We don’t have a lot of models like this that tell us where individual species may go under different scenarios,” Stinson said. “Ecologists are working on doing this type of study for more species, but there are not always enough data points from around the world. Individual species data are rare.”

But this study was possible because, as anyone with hay fever knows, “ragweed happens to be quite abundant,” she said.

Reposted with permission from our media associate Nexus Media.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe