By Lucas Davis

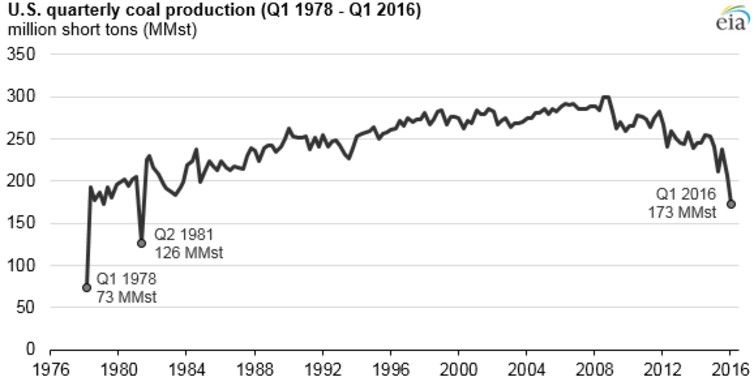

This is the worst year in decades for U.S. coal. During the first six months of 2016, U.S. coal production was down a staggering 28 percent compared to 2015 and down 33 percent compared to 2014. For the first time ever, natural gas overtook coal as the top source of U.S. electricity generation last year and remains that way. Over the past five years, Appalachian coal production has been cut in half and many coal-burning power plants have been retired.

This is a remarkable decline. From its peak in 2008, U.S. coal production has declined by 500 million tons per year—that’s 3,000 fewer pounds of coal per year for each man, woman and child in the U.S. A typical 60-foot train car holds 100 tons of coal, so the decline is the equivalent of five million fewer train cars each year, enough to go twice around the Earth.

This dramatic change has meant tens of thousands of lost coal jobs, raising many difficult social and policy questions for coal communities. But it’s an unequivocal benefit for the local and global environment. The question now is whether the trend will continue in the U.S. and, more importantly, in fast-growing economies around the world.

Health Benefits from Coal’s Decline

Coal is 50 percent carbon, so burning less coal means lower carbon dioxide emissions. More than 90 percent of U.S. coal is used in electricity generation, so as cheap natural gas and environmental regulations have pushed out coal, this has decreased the carbon intensity of U.S. electricity generation and is the main reason why U.S. carbon dioxide emissions are down 12 percent compared to 2005.

Perhaps even more important, burning less coal means less air pollution. Since 2010, U.S. sulfur dioxide emissions have decreased 57 percent and nitrogen oxide emissions have decreased 19 percent. These steep declines reflect less coal being burned, as well as upgraded pollution control equipment at about one-quarter of existing coal plants in response to new rules from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

These reductions are important because air pollution is a major health risk. Stroke, heart disease, lung cancer, respiratory disease and asthma are all associated with air pollution. Burning coal is about 18 times worse than burning natural gas in terms of local air pollution so substituting natural gas for coal lowers health risks substantially.

Economists have calculated that the environmental damages from coal are US$28 per megawatt-hour for air pollution and $36 per megawatt-hour for carbon dioxide. U.S. coal generation is down from its peak by at least 700 million megawatt-hours annually, so this is $45 billion annually in environmental benefits. The decline of coal is good for human health and good for the environment.

India and China

The global outlook for coal is more mixed. India, for example, has doubled coal consumption since 2005 and now exceeds U.S. consumption. Energy consumption in India and other developing countries has consistently exceeded forecasts, so don’t be surprised if coal consumption continues to surge upward in low-income countries.

In middle-income countries, however, there are signs that coal consumption may be slowing down. Low natural gas prices and environmental concerns are challenging coal not only in the U.S. but around the world and forecasts from the Energy Information Administration and BP have global coal consumption slowing considerably over the next several years.

Particularly important is China, where coal consumption almost tripled between 2000 and 2012, but more recently has slowed considerably. Some are arguing that China’s coal consumption may have already peaked, as the Chinese economy shifts away from heavy industry and toward cleaner energy sources. If correct, this is an astonishing development, as China represents 50 percent of global coal consumption and because previous projections had put China’s peak at 2030 or beyond.

The recent experience in India and China point to what environmental economists call the “Environmental Kuznet’s Curve.” This is the idea that as a country grows richer, pollution follows an inverse “U” pattern, first increasing at low-income levels, then eventually decreasing as a country grows richer. India is on the steep upward part of the curve, while China is, perhaps, reaching the peak.

Global Health Benefits of Cutting Coal

A global decrease in coal consumption would have enormous environmental benefits. Whereas most U.S. coal plants are equipped with scrubbers and other pollution control equipment, this is not the case in many other parts of the world. Thus, moving off coal could yield much larger reductions in sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and other pollutants than even the sizeable recent U.S. declines.

Of course, countries like China could also install scrubbers and keep using coal, thereby addressing local air pollution without lowering carbon dioxide emissions. But at some level of relative costs, it becomes cheaper to simply start with a cleaner generation source. Scrubbers and other pollution control equipment are expensive to install and expensive to run, which hurts the economics of coal-fired power plants relative to natural gas and renewables.

Broader declines in coal consumption would go a long way toward meeting the world’s climate goals. We still use globally more than 1.2 tons of coal annually per person. More than 40 percent of total global carbon dioxide emissions come from coal, so global climate change policy has correctly focused squarely on reducing coal consumption.

If the recent U.S. declines are indicative of what is to be expected elsewhere in the world, then this goal appears to be becoming more attainable, which is very good news for the global environment.

Lucas Davis is an associate professor at the Haas School of Business, faculty director at the Energy Institute at Haas and research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

This article was reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe