Suspected Elephant Kidnappers in Sri Lanka Can Keep the Animals, Court Rules

Elephant calves that were taken from the wild. Sajeewa Chamikara

By Malaka Rodrigo

UDAWALAWE, Sri Lanka — Environmental activists in Sri Lanka have slammed a court order releasing endangered elephants into the custody of individuals suspected of involvement in their illegal capture and trade.

Thirty-eight captive Sri Lankan elephants (Elephas maximus maximus) were taken into the custody of the state in 2015 following an investigation that uncovered a trafficking racket targeting baby elephants born in the wild. On Sept. 6 this year, however, acting on a request from the Attorney General’s Department, a court has ordered 14 of the elephants to be released back to their keepers — the same people they were confiscated from six years ago on trafficking suspicions and who remain under investigation.

“Illegal catching of elephant calves from the wild is the most hideous wildlife crime in Sri Lanka, and we are extremely concerned about how things are unfolding,” said environmental lawyer Jagath Gunawardana. He added there was a lot of ambiguity surrounding the circumstances in which the elephants were released.

The owners retook possession of the elephants the day after the court order, which the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ), a leading NGO, has now filed a case against.

A recent study identifies 55 cases of elephant abductions in Sri Lanka. This calf found in 2009 in the southern town of Balangoda died a few days later. Sajeewa Chamikara

‘Regularizing Theft’

Activists see this latest development in the case as part of wider moves by those in power to effectively whitewash the provenance of captive elephants in Sri Lanka, where taking the animals from the wild has been illegal since 1980.

The AG’s request for the elephants to be returned to the owners followed the issuance of a government gazette on Aug. 19 that effectively loosened the requirements for keeping captive elephants. Under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance (FFPO), possession of an elephant requires a license issued by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC). But the gazette introduced provisions allowing elephants kept without a license to be registered without this paperwork.

“Bringing in a regulation to register those elephants without proper registration during the pendency of a court case being heard is a move to regularize theft,” Gunawardana told Mongabay.

Sujeewa, shown here in 2012, was taken from the wild when she was about 3 years old. She is now 15 years old and has recently given birth. Sajeewa Chamikara

Beasts of Burden and Status

In Sri Lanka, captive elephants have been an integral part of cultural events for centuries, and are today a popular tourist attraction, including in elephant safaris, where visitors ride on the endangered species.

Up until 1980, the government allowed elephants to be caught from the wild. Since then, the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage (PEO), which also runs a successful captive-breeding program, has become the main source for Sri Lanka’s demand for captive elephants.

Today, there are 210 elephants in captivity in Sri Lanka. Of these, 102 are in state-owned facilities, and the rest are held by private keepers, including high-profile individuals and Buddhist clergy.

Private owners generally keep elephants for one of two reasons: for work, or for status. Elephants under the former category are trained to participate in cultural events, tourist activities, and are even used for logging activities. Those in the latter category are kept as a symbol of prestige and class. In both cases, the demand for captive elephants clearly exists, and it’s this that drives the abduction of baby elephants from the wild, conservationists say.

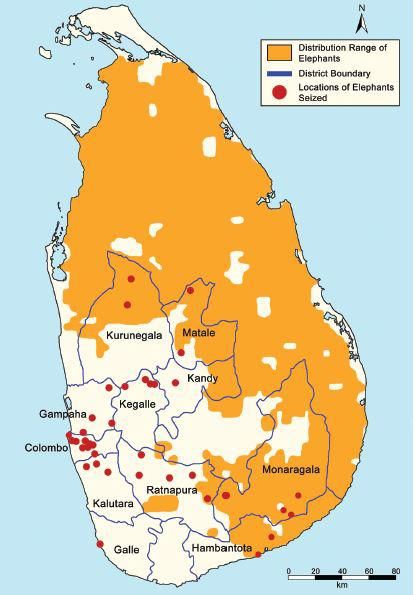

This map shows the locations from where 38 captive elephants were confiscated in 2015 after they were found to have been illegally removed from the wild by traffickers. Supun Lahiru Prakash

Baby Elephants Out of the Blue

Signs that an organized elephant-trafficking racket was at work emerged after 2008, as calves started to appear at various cultural events. Sri Lanka didn’t have a breeding program among the privately held elephants, and there were no records of elephant births within this population, so environmentalists began suspecting something wasn’t right.

At the same time, isolated incidents of illegally kept baby elephants began being reported from different parts of the country. A covert year-long investigation by a group of environmentalists, including Sajeewa Chamikara, resulted in the publication of a list of 23 elephant calves suspected to have been illegally taken from the wild in 2013. A study analyzing the period from 2008 to 2018 revealed 55 instances of baby elephants being snatched from the wild.

“Even under proper facilities, there are mortalities of nearly 40% of orphaned baby elephants, so in the process of illegally acquiring elephants, minimum facilities would result in a much higher mortality rate, indicating that victims of this ongoing wildlife crime being much higher in number,” said Supun Lahiru Prakash, lead author of the study.

Elephant herds, especially the mother elephant, are very protective of calves. This suggests it’s highly likely that the traffickers kill the mother elephant to get the calf, Chamikara told Mongabay.

But even if a calf survives such an encounter, it’s still not out of danger. The Udawalawe Elephant Transit Home (ETH) in southern Sri Lanka takes in and cares for orphaned calves, rehabilitating them so that they can eventually be released back into the wild. Upon release, they’re still vulnerable to traffickers, and researchers are now studying whether these elephants too are being targeted for kidnap.

Captive elephants are an integral part of Sri Lanka’s cultural events and are regularly used in Buddhist religious processions to carry caskets bearing relics. Dilsiri Welikala

‘Elephant Mafia’

Politicians, high-ranking officials, wildlife officers, and even trained veterinary surgeons are linked to the elephant trafficking racket, which has the blessings of top leaders, says Rukshan Jayawardene, a conservationist.

As all captive elephants must be registered with the DWC, the elephant registry is a starting point to investigate the trafficking racket. But in 2015, this elephant registry went missing for several weeks. When it reappeared, some of the entries had been destroyed or amended — evidence, conservationists say, of the influence wielded by this “elephant mafia.” Given half a chance, they will do this again, Jayawardene said.

After the 2015 investigation that led to the state seizing the 38 elephants, there was considerable pressure on the DWC to get the elephants released back to their keepers.

Sumith Pilapitiya, who was the director-general of the DWC for a short period in 2016, said the country’s top leaders wanted him to request a court order for the release of the animals from DWC custody.

“As the head of the national agency dedicated to wildlife conservation, it was not my responsibility to ensure adequate elephants are available at various cultural events,” he told Mongabay. “My job was to conserve wildlife and ensure baby elephants were not illegally captured from the wild. I flatly refused to pursue the suggested path.”

These elephants, now juveniles, have lived in isolation for more than six years, with minimum human intervention to improve the chances of a successful return to the wild. If the traffickers have their way and the elephants are instead returned to captivity, the outcome would be devastating, says Panchali Panapitiya of the advocacy group Rally for Animal Rights & Environment (RARE). Having grown “wilder” in isolation, getting them back into a state of docility will require the use of brutal tactics to crush their spirit and “retrain” them, she said.

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe