Battle Lines Are Drawn as Congress Reforms the 40-Year-Old Toxic Substances Control Act

2016 marks the 40th anniversary of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). But there is little to celebrate. Signed into law by President Gerald Ford in 1976, the TSCA has been sharply criticized for failing at what it was meant to do: protect public health and the environment from the tens of thousands of chemicals that saturate the marketplace and the hundreds of new ones that are introduced every year.

Adding to the concern is the fact that the law hasn’t been significantly updated since it was enacted, during which time some 22,000 new chemicals have entered American commerce, with around 700 new ones rolled out each year. Many of these chemicals—most of which did not previously exist in nature—have been widely dispersed throughout the environment, into the air, soil and water where some will persist for decades or even centuries.

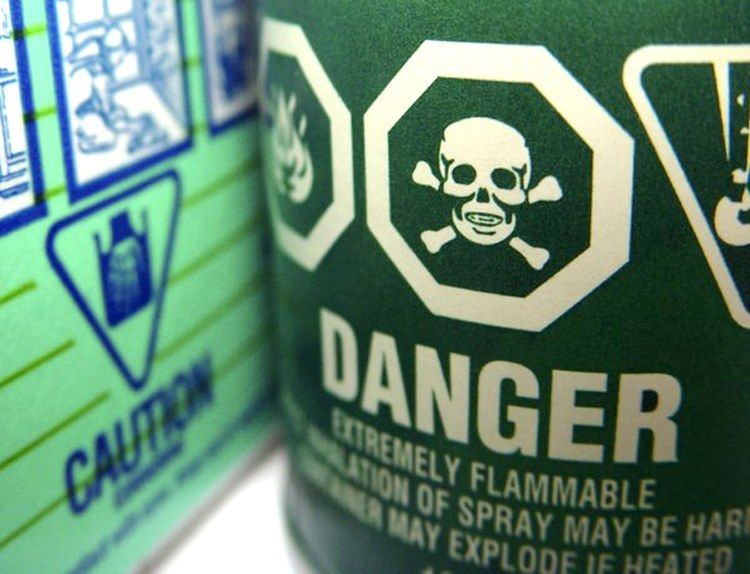

The figures are staggering. Every year, around 4 billion pounds of toxic chemicals are released by American industries. In 2011 alone, 16 new chemicals accounted for nearly 1 million pounds. There is far too little testing of these substances: Only a fraction of the nearly 3,000 high-production-volume (HPV) chemicals—chemicals that have an annual production run of at least one million pounds—have been studied for their potential toxicity. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the agency has “only been able to require testing on a little more than 200 existing chemicals” out of the 62,000 that have been introduced since the TSCA’s enactment. The EPA has banned just five.

It has been a long time in coming, but after several years of negotiations, two bills seeking to overhaul the TSCA have finally been passed in both houses of Congress. And while one might assume a federal effort to improve the TSCA would receive widespread popular support (a nationwide poll conducted in 2012 found that nearly 74 percent of Americans believe the threat of chemical exposure to people’s health is serious), the legislation has been met with fierce opposition—and not from the chemical industry.

State authorities weigh in on #TSCA reform legislation moving through U.S. Congress https://t.co/MpW3VYLtJW pic.twitter.com/EEG8kHCPdP

— EDF Health (@EDFHealth) February 9, 2016

For decades, regulating chemicals in the U.S. has been a “too little, too late” exercise in futility. Now that Washington is on the verge of a major overhaul, chemical policy reform has become a pitched battleground. Several stakeholders have been vying for leverage, from federal lawmakers and state attorneys general, to chemical industry lobbyists and community activists, to public and environmental health activists. How did something so basic as keeping people and animals safe from dangerous substances become such a highly politicized arena?

One Word: Plastics

Since World War II, some 80,000 new chemicals have been invented. But it wasn’t until the early 1970s when the President’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), formed in 1969 under the Nixon administration, proposed federal legislation to regulate American commerce in chemical substances. So why did it take so long for the government to address the potential health and environmental effects of chemicals? It’s a familiar and tragic narrative: Public health regularly takes a back seat to corporate interests. Time and time again, major toxic disasters occur, reminding us just how susceptible humans, animals and the environment are to toxins produced by industrial activity. Look at Love Canal in Niagara Falls in the 1950s, Times Beach, Missouri in the 1970s or the Summitville mine in Colorado in the 1980s. More recently, there was the Exide lead contamination in Los Angeles. Today, the Flint water crisis unfolds in Michigan.

While big disasters such as these make national headlines, it was actually a series of festering environmental contamination events around the country—and the community activism that gradually grew around them—that set the stage for the TSCA’s passage.

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were contaminating the Hudson River; polybrominated biphenyls (PBBs) were contaminating agricultural produce in Michigan; and chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) emissions were depleting the ozone layer. But it was the process behind making polyvinyl chloride, a plastic commonly known as PVC, that was ultimately the driving force that finally got the law passed. In their 2002 book, Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution, public health historians Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner write, “While the discovery of various kinds of industrial pollution had led the EPA to begin pressing for passage of Toxic Substances Control Act, the publicity and seriousness of the vinyl crisis would become the impetus for more assertive efforts to get TSCA passed, with a view toward regulating more chemicals than vinyl chloride.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe