The full body shot of P22 was then adapted for the campaign as a cardboard cut-out. Comedian Rainn Wilson of Soul Pancake fame introduces a YouTube video by saying, “My good friend and homeboy P22 is stuck in Griffith Park!” A montage of clips shows P22 in a convertible, standing on a swimming pool float, riding a kayak down the LA River and taking the merry-go-round in Griffith Park. He’s even become a cartoon character. “You have to anthropomorphize ,” Pratt argues. “It’s not a bad thing. You want people to relate, to have day-to-day relationships with animals. Otherwise, we won’t save them.” At the same time, she worries about her portrayal. “The cat is thinking, ‘What is Pratt up to now?’ He’ll eat me someday.”

as a cardboard cut-out. Photo credit: Elizabeth Rose-Marini

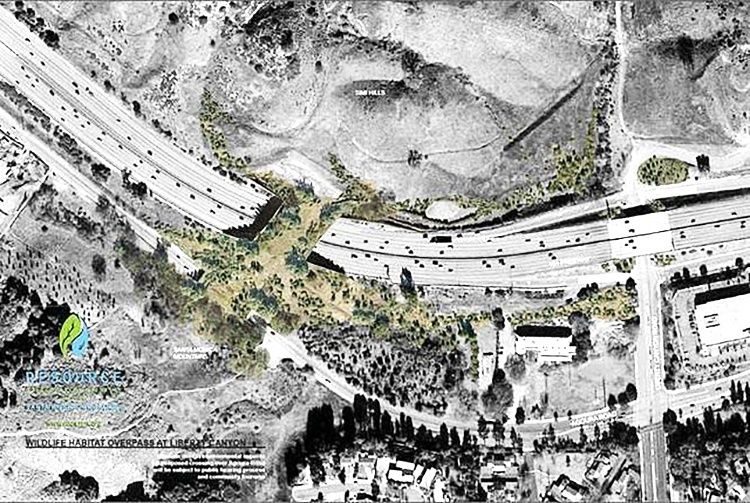

Save LA Cougars has already raised $1 million and needs to raise and additional $3 million by April 2018 to pay for a detailed project design and environmental reviews of the proposed bridge for wildlife. Once these documents are completed, the project is considered to be “shovel ready” and eligible for federal funding. A major lobbying effort by the region’s political leaders to help fund the project is anticipated.

P22’s celebrity stature makes the proposed Liberty Canyon Wildlife Crossing a perfect LA story. But this isn’t just about the glamour of charismatic megafauna. Wildlife advocates say the campaign to fund and build the wildlife corridor is essential to bring attention to a second and less famous, trapped cougar population in the Santa Ana Mountains in Orange and San Diego counties, to the south.

Chris Basilevac , director of the Nature Conservancy’s land protection program in Southern California, explains: “That [proposed] crossing has lands already protected on both sides of the 101 freeway. If they can pave the way there with Caltrans [the California highway agency] and other sources, that helps our chances a lot to make it happen down here.” Basilevac has worked for 11 years buying land along a major north-south corridor, Interstate 15, in the hope of creating a regional network of crossings for mountain lions and other animals.

“It’s an emotional roller coaster,” Basilevac says of his efforts to purchase lands. In Orange and San Diego counties, he says, “only a small percentage of the sellers are conservation-minded.” Basilevac deals mainly with investors who bought parcels (about 15 to 100-acres in size) as investment properties and are looking for profits. If they bought at the height of the last real estate boom, their property is often appraised at less now. According to its bylaws, the Nature Conservancy cannot pay more than appraised value. “It’s really a matter of trying to make them an attractive offer. Sometimes we ask them to sell at less than appraised value and try to find a way to make it up, say by making a charitable contribution as a tax write-off.”

Exactly which lands Basilevac and the Nature Conservancy target for buying is informed by the research of wildlife veterinarian Winston Vickers. Vickers works as a UC-Davis based researcher under contract for the Nature Conservancy and several Orange, San Diego and Riverside county transportation and public lands agencies. Vickers and his associates track mountain lions in the Santa Ana Mountains (which run north-south) and the eastern Peninsular Ranges (which run east-west) and intersect the Santa Ana’s near Temecula, in south Orange County. From early 2001 through Dec. 2013 Vickers’s team captured and radio collared 43 lions in the eastern Peninsular Ranges east of I-15 and 31 in the Santa Ana Mountains west of I-15.

Not a single cougar of the 43 collared in the eastern Peninsular Range successfully crossed I-15 to the west into the Santa Ana Mountains during the entire 13-year study. Among the 31 lions tracked in the Santa Ana Mountains, only one, M86, was found to have genes that originated among the eastern cougars. Although three of his descendants are still alive, that’s not enough to overcome the Santa Ana cougars’ genetic bottleneck and isolation. Thus the small population of lions in the Santa Ana’s—no more than 17 to 27 animals at any given time—suffers from the same crisis as do the Santa Monica Mountain cougars. The annual survival rate for that population is even less—56.5 percent. Unless the I-15 can be fitted with underpasses or bridges of some kind, then the Santa Ana Mountains population is “at risk for demographic collapse,” says Vickers.

While Basilevac negotiates with landowners along I-15 to buy land for wildlife corridors, Vickers and his team try to keep the Santa Ana mountain population alive by reducing the high number of animals killed each year crossing the 241 toll way along a stretch of public lands in Orange County. They are building a 11-13-foot-high, 7-mile-long fence to keep cougars and their prey, mule deer, from crossing the toll way and instead channel them into a few underpasses.

When I met Vickers and his assistant, Jamie Bourdon in August, they were fitting Bushnell Trail cameras to the telephone poles at what are called “jump-out” ramps—places where animals who somehow get onto the toll way can jump back into the hills. Jamie wore a White Panther Party t-shirt complete with a pouncing panther logo, a design from the late 1960s. At the time, the White Panther Party was founded as a far-left, culturally revolutionary companion to the Black Panther Party. In 2015, Bourdon’s t-shirt serves the same function as Pratt’s tattoo—a statement of totemic kinship.

While Bourdon stood on a ladder and began to focus the infrared and motion-detector triggered cameras, Vickers bent over at the waist, dangled his arms and shuffled up and down the earthen ramps, performing what was in essence a ritual “deer dance.” No doubt both men saw the dance in the service of science, necessary to aim the trail cams and accurately record which animals used a ramp to escape. But no one from a hunting-gathering society would be confused: Vickers’s deer dance honored the mule deer and their cougar predator.

The intense scientific monitoring and the sophisticated engineering behind the fences, underpasses and bridges is but the physical embodiment of an important cultural change. In Southern California, wild dreams are being acted out in the effort to boost the cougar’s chances of survival. The conservation efforts symbolize that if we let the mountain lions die on the freeways and in their confined territories, then we will also lose part of ourselves.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

#BearSelfies Force Colorado Park to Close

Beloved Elephant Yongki Killed by Ivory Poachers, Sparks Outrage

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe