Nitrous oxide, the main ingredient in laughing gas, does more than just act as a nerve agent; it is a powerful greenhouse gas. It is 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide and scientists believe could be leaking from ancient reservoirs beneath Arctic permafrost.

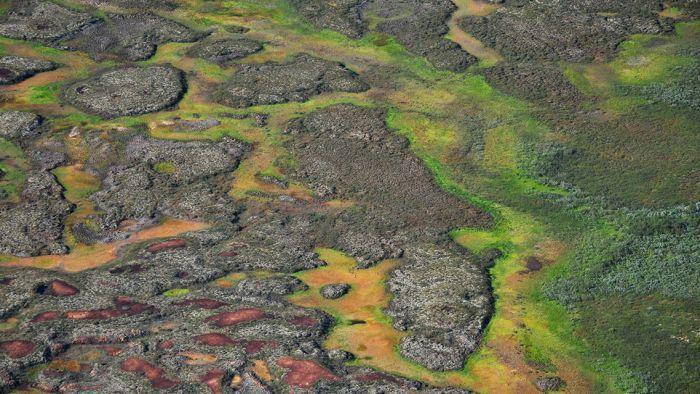

A team of researchers from Sweden, Finland and Denmark analyzed 16 frozen peat cores from the Finnish Lapland and melted them in a specialized warming chamber in their lab. The goal was to see what kind of elements would be emitted if warming temperatures were to ensue in the Arctic. Their study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals that nitrous oxide could emerge from more than one-fourth of the Arctic’s peatland surfaces.

There would be a five-fold increase in the amount of nitrous oxide released, compared to the average seasonal thawing of the uppermost part of the peat. The emissions would be so high, they’d match that of tropical rainforests, which are the highest polluters of nitrous oxide.

In fact, due to climate change in the region, there are already “hotspots” releasing the gas at a much higher rate than expected. This is what prompted the researchers to analyze nitrous oxide in the first place, since it usually isn’t seen as much of a threat compared to methane and CO2.

“Usually nitrous oxide emissions from Arctic soils were believed to be negligible, basically because the nitrogen content—the substrate for production of N2O—is probably rather low, or the production rate is rather low due to the cold climate,” said Carolina Voigt, from the University of Eastern Finland.

Another concern from the study is the lack of vegetation in the Arctic, without plants to suck up the nitrous oxide, it will go straight into the atmosphere.

“Plants take up nitrogen from the surface soil so they reduce the nitrogen pool that’s available for N2O production in the soil profile, so plants are very effective at reducing N20 emissions,” Voigt said.

Voigt said the wetter the conditions are, the less likely nitrous oxide is to be released from the peat.

“So future N2O emissions in the Arctic probably will depend largely on how vegetation and moisture conditions will develop in the future,” she said.

With Arctic warming at an all time high, however, this may soon be the reality.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe