Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, has long been tied to environmental risks such as spills. The frequency of spills, however, has long been murky since states do not release standardized data.

Estimates from the U.S. Environment Protection Agency (EPA) vary wildly.

“The number of spills nationally could range from approximately 100 to 3,700 spills annually, assuming 25,000 to 30,000 new wells are fractured per year,” the agency said in a June 2015 report. Also, the EPA reported only 457 spills related to fracking in 11 states between 2006 and 2012.

But now, a new study suggests that fracking-related spills occur at a much higher rate.

The analysis, published Feb. 21 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, revealed 6,648 spills in four states alone—Colorado, New Mexico, North Dakota and Pennsylvania—in 10 years.

The researchers determined that up to 16 percent of fracked oil and gas wells spill hydrocarbons, chemically laden water, fracking fluids and other substances.

EPA Watered Down Major #Fracking Study to Downplay Water Contamination Risks https://t.co/9HhJdrSZ1R @GreenpeaceUK @globalactplan

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) December 3, 2016

For the study, the researchers examined state-level spill data to characterize spills associated with unconventional oil and gas development at 31,481 fracked wells in the four states between 2005 and 2014.

“On average, that’s equivalent to 55 spills per 1,000 wells in any given year,” lead author Lauren Patterson, a policy associate at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, told ResearchGate.

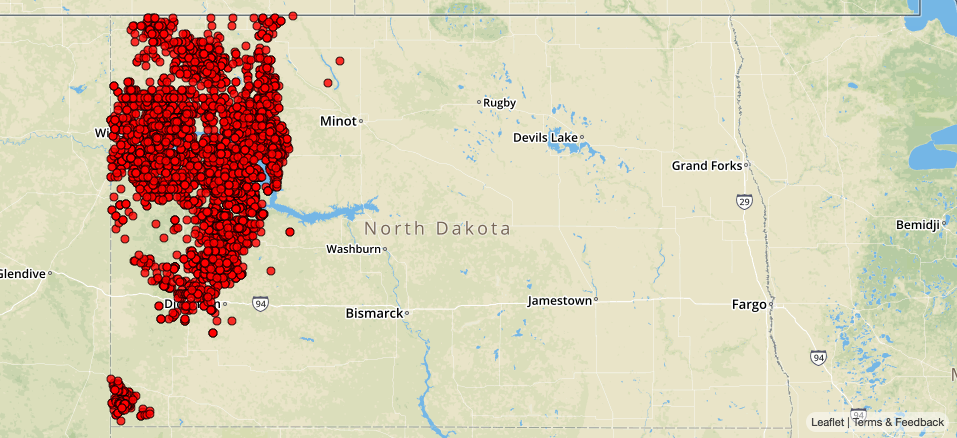

North Dakota reported the highest spill rate, with 4,453 incidents. Pennsylvania reported 1,293, Colorado reported 476 and New Mexico reported 426. The researchers created an interactive map of spill sites in the four states.

Although North Dakota is rich in oil, the state’s higher spill rate can be explained by varying state reporting requirements. North Dakota is required to report any spill larger than 42 gallons whereas requirement in Colorado and New Mexico is 210 gallons.

Patterson points out that the different reporting requirements are a problem.

“Our study concludes that making state spill data more uniform and accessible could provide stakeholders with important information on where to target efforts for locating and preventing future spills,” she told ResearchGate. “States would benefit from setting reporting requirements that generate actionable information—that is, information regulators and industry can use to identify and respond to risk ‘hot spots.’ It would also be beneficial to standardize how spills are reported. This would improve accuracy and make the data usable to understand spill risks.”

9,442 Citizen-Reported Fracking Complaints Reveal 12-Years of Suppressed Data https://t.co/I8IpPRk6zR @talkfracking @AntiFrackinguk

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) January 31, 2017

The reason why the researchers’ numbers vastly exceeded the 457 spills estimated by the EPA is because the agency only accounted for spills during the hydraulic fracturing stage itself, rather than the entire process of unconventional oil and gas production.

“Understanding spills at all stages of well development is important because preparing for hydraulic fracturing requires the transport of more materials to and from well sites and storage of these materials on site,” Patterson explained. “Investigating all stages helps to shed further light on the spills that can occur at all types of wells—not just unconventional ones.”

For instance, the researchers found that 50 percent of spills were related to storage and moving fluids via pipelines.

“The causes are quite varied,” Patterson told BBC. “Equipment failure was the greatest factor, the loading and unloading of trucks with material had a lot more human error than other places.”

220 'Significant' Pipeline Spills Already This Year Exposes Troubling Safety Record https://t.co/pxhlC3pf06 @PriceofOil @350 @billmckibben

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) October 25, 2016

For the four states studied, most spills occurred in the the first three years of a well’s life, when drilling and hydraulic fracturing occurred and production volumes were highest.

Additionally, a significant portion of spills (26 percent in Colorado, 53 percent in North Dakota) occurred at wells with more than one spill, suggesting that wells where spills have already occurred merit closer attention.

“Analyses like this one are so important, to define and mitigate risk to water supplies and human health,” said Kate Konschnik, director of the Harvard Law School’s Environmental Policy Initiative in a statement. “Writing state reporting rules with these factors in mind is critical, to ensure that the right data are available—and in an accessible format—for industry, states and the research community.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe