EcoWatch Reviews

At EcoWatch, we're all about finding sustainable solutions for homeowner headaches. As such, environmental friendliness is one of our top criteria when we review companies.

About EcoWatch Reviews

Founded in 2005 as an environmental newspaper, EcoWatch is a long-time leader in environmental news. Today, we are a digital platform still dedicated to publishing quality, science-based content on environmental issues, causes and most importantly, solutions.

The EcoWatch Reviews team supplements our newsroom, aiming to connect our readers with sustainable solutions and reputable companies for a healthier planet and life. We believe that individual actions are a powerful force and that, together, we can make better choices to promote a better future for both wildlife and humanity.

Why Can You Trust EcoWatch?

We work with a panel of sustainability experts to create unbiased reviews that empower you to make the right choice for your home. No other review site has as long a history covering the issues that we do, which means we have access to more data and insider information than other sites. Our reviews and rankings are never affected by revenue or partnerships.

Which Categories Does EcoWatch Review And Why?

At EcoWatch, we’re focused on helping our readers make the best decisions possible to improve the health of the environment. We felt there was a need to serve our readers and provide reviews of providers from a sustainability perspective. This approach allows us to work parallel to our newsroom, providing solutions to our readers who are looking to make a difference through their actions, whether it be making their homes more energy efficient, choosing a more sustainable lawn care provider or opting for a renewable power plan.

Currently, we review providers in the solar energy, deregulated energy, roofing, gutters and windows categories. Our aim is to highlight providers that offer sustainable products and services while providing great customer care.

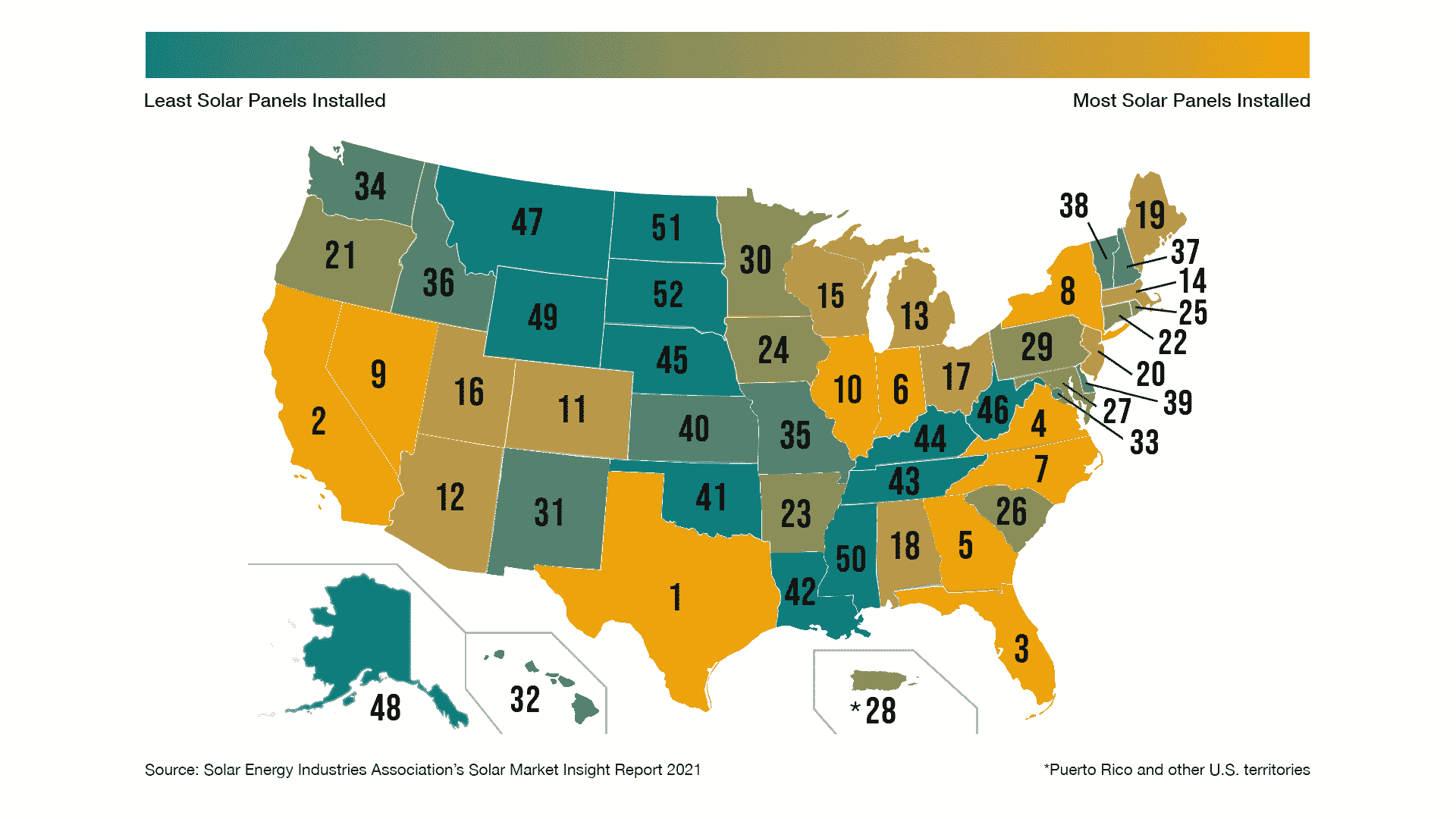

Solar

Installing solar panels is one of the most practical investments that homeowners can make. Not only do solar panels reduce your dependence on traditional energy sources, but they can offset the majority of your electricity costs as well. Under the right circumstances, some solar installations can generate over $50,000 in lifetime energy savings for a homeowner.

- Protection from fluctuating energy costs

- Improved resilience in the face of extreme weather and power outages

- Stimulated job growth in the U.S.

An investment in solar can be hefty, but it’s important to remember you’re effectively purchasing 25+ years of electricity upfront. In most cases, the cost of sticking with your utility for that same amount of time will be more than the cost of an investment in solar today.

How Does Solar Lower Your Carbon Footprint?

Installing solar panels on your home serves as one of the most accessible ways for everyday citizens to help lower their impact. For example, a 10 kW system that produces 12,500 kWh of electricity per year helps to avoid 8.9 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions. This is equivalent to:

- 9,801 pounds of coal burned

- The carbon sequestered by 10.5 acres of forest in one year

- 1,000 gallons of gasoline consumed

More on Solar Energy

What Are the Different Types of Solar Panels?

Wondering what types of solar panels are best for your home? We’ll cover the most popular types of solar panels that homeowners can choose from for their homes, such as:

- Monocrystalline panels

- Polycrystalline panels

- Thin-film panels

Click the link below to read the article.

How Much Do Solar Panels Cost?

Are you wondering what it might cost for you to go solar? We’ll go over how much homeowners typically pay for panels across the U.S. and cover things like:

- What affects the price of solar panels

- What the federal solar tax credit is

- Which solar financing options are available

Click the link below to read the article.

Related Solar Guides

Deregulated Energy

Energy deregulation gives consumers the power to choose their own energy provider. It works similar to picking your own internet provider — you’ll have multiple options depending on where you live, each offering its own rates and plans.

There are several benefits to being able to choose your own energy provider, including:

- The ability to select the best rates

- Finding contract terms that fit your needs

- Choosing green energy sources like wind, solar or hydropower

Supporting energy providers that source their power from renewable sources gives more power (literally and figuratively) to the renewable energy industry. Enough support will have more providers turning away from harmful energy sources, like fossil fuels, in search of more environmentally-friendly alternatives.

What Should You Look For in an Energy Provider?

Whether you’re just moved to a state with a deregulated energy market or you’re looking to save money by switching providers, here’s what you should look for in an energy provider:

- Type of plans offered and if they fit your needs

- Green-sourced energy plans

- Reasonable electricity rates and contract terms

- History of trustworthy behavior

- Positive customer reviews

More on Deregulated Energy

Which Provider Has the Best Electricity Rates?

Are you looking for an energy provider? In this guide, we outline our top 5 recommended energy providers with low electric rates for renewable plans. We also cover:

- Current average retail rates of electricity

- Best types of plans to consider

- Frequently asked questions when choosing energy plans

Click below to read the full article.

How Does Deregulated Energy Work?

Understanding the deregulated energy market can be challenging. To help make it easier, the EcoWatch team compiled a guide to cover topics such as:

- What is electricity deregulation? How does it work?

- Regulated vs. deregulated electricity

- Which states have deregulated electricity?

Click the link below to read the article.

Windows

Having windows that are made out of traditional materials or that are outdated or damaged is bad news for both your wallet and the environment. Research shows that you could be losing 25-30% of your home’s heat or air conditioning via inadequate windows, forcing your HVAC system to use far more energy than it should.

Choosing windows that are more energy efficient can be extremely beneficial for homeowners, helping you to:

- Save money on heating and cooling costs

- Keep your house at a more comfortable temperature

- Protect your family and your belongings from UV damage

- Help the environment by lowering your energy usage

How Can You Tell If Your Windows Are Energy-Efficient?

If you want the most energy-efficient and eco-friendly windows, there are a few things you should look out for:

- Energy Star certifications

- Double- or triple-paned glass

- Low-E (low-emissivity) glazes

- Fixed picture or hinged window designs

More on Windows

Our Highest-Recommended Window Replacement Installation Companies

EcoWatch ranks window installation companies based on energy efficiency while also balancing cost, customer satisfaction and more. Here, we cover a few of the top eco-friendly window installers in the U.S., plus topics such as:

- What to look for in a quality window replacement installer

- How to hire a great window installation provider

- Our preferred window installers

Click below to read the full article.

Complete Guide to Energy Efficient Windows

If you need to replace your home windows and are considering energy-efficient options to reduce your utility bills and keep your home more comfortable, you’re in the right place. In this guide you’ll learn:

- What are energy-efficient windows?

- What are the benefits of energy-efficient windows?

- What energy-efficient window options are there?

Click the link below to read the article.

Related Window Guides

Gutters

If you’re installing gutters or gutter guards, you’re probably thinking about their utility rather than focusing on their environmental impact. However, many common gutter and gutter guard materials can have negative impacts on the environment.

When choosing products, steer clear of materials including polyvinyl chloride, better known as PVC. Traditional PVC becomes brittle when exposed to UV light, contains harmful chemicals and is not recyclable.

We recommend looking for the following materials, which have a lesser impact on the environment:

- uPVC (unplasticised PVC)

- Aluminum

- Copper

- Galvanized steel

- Titanium zinc

We also recommend attaching your gutters to a rain barrel or other rainwater catchment system to use for watering your lawn or nonedible plants.

Do You Need Gutter Guards?

If your gutters frequently get clogged and cause water to spill over onto the ground, it may be damaging the soil below. Plus, if you’re using a rain catchment system, spillover will wastewater that could be used around your home.

However, gutter guards aren’t cheap, and they can be a hassle to install, so many homeowners wonder if they’re worth the investment. Here are some reasons you might consider installing gutter guards:

- They stop blockages and improve gutter water flow

- They help avoid pest and insect infestations

- They can help prevent premature rust and corrosion, meaning you’ll need to replace your gutters less often

- They reduce the need for frequent gutter cleaning

More on Gutters

Our Highest-Recommended Gutter Gutter Guards

Wondering if you should invest in gutter guards for your home? In this guide, we’ll go over several key aspects of installing gutter guards on your gutters, including:

- What to look for in a quality gutter guards

- Why gutter guards can help your home

- Our preferred gutter guard installers

Click below to read the full article.

Average Gutter Guard Installation Costs

Are gutter guards actually worth it? In this guide, we’ll cover several of the key questions that homeowners usually have about gutter guard installation, including:

- What different types of gutter guards cost

- Why gutter guards can save you money

- How much you can expect to pay for gutter guard installation

Click below to read the full article.

Roofing

Your roof is a fundamental part of your home, and some roofing options are greener than others.

Asphalt roofs are popular because of their low cost, but they require more frequent replacement and aren’t the most environmentally friendly. Other roofing materials like metal or clay are long-lasting, recyclable and can even improve the energy efficiency of your home.

Roofing materials that are more sustainable tend to be:

- More durable: Environmentally friendly roofing materials like metal and clay tend to last longer and require less maintenance than traditional asphalt roofing.

- More energy-efficient: Sustainable roofing materials help insulate your home, lowering your carbon footprint and utility bills.

- Less wasteful: We recommend roofing materials that are easily recyclable and long-lasting to reduce unnecessary waste.

How Do I Know If I Need a New Roof?

If you’re noticing one or more of the following signs, it may mean that you need a new roof:

- Your roof is sagging

- Some of your shingles are curling, buckling or missing

- You see signs of water damage like rot, mold, stains or peeling paint in places like your attic, walls or ceilings

- Your energy bills are higher than usual

- Your roof’s warranty is set to expire soon

- A roofing contractor has inspected your roof and finds that it is beyond a simple repair

More on Roofing

Metal Roof Installation & Cost

What are the benefits of a metal roof? Learn more about costs, and why you might consider replacing your roof with a new metal one.

- Different metal roof types such as Zinc, Copper and Tin can provide added benefits.

- Metal roofs tend to be more durable

- And metal roofs are great when adding Solar panels

Best National Roofing Contractors

Thinking of replacing your roof? In this guide, you’ll learn what the top ranked national roofing companies are and how to choose the best one including the following:

- Best time of the year to replace your roof

- How long a roof replacement takes

- Best contractors to go with

Click below to read the full article.

Editorial Contributers

Karsten Neumeister, EcoWatch Editor

Karsten is an environmental specialist passionate about sustainable development. Before joining EcoWatch, Karsten worked in the energy sector of New Orleans, focusing on renewable energy policy and technology.

Kristina Zagame, EcoWatch Writer

Kristina is a writer with expertise in solar and other energy-related topcis. Before joining EcoWatch, Kristina was a TV news reporter and producer, covering topics including West Coast wildfires and hurricane relief efforts.

Dan Simms, EcoWatch Writer

Dan is an experienced writer and solar and EV advocate. Much of his work has focused on the potential of solar power and deregulated energy, but he also writes on related topics like real estate and economics.

Roger Horowitz, EcoWatch Solar Adviser

Roger empowers communities to adopt solar as the director of Go Solar programs at Solar United Neighbors. SUN, a nonprofit, fights for energy rights and builds solar co-ops to make it easier for homeowners to make the switch.

Melissa Smith, EcoWatch Director of Content

Melissa is an editor and content expert who has worked extensively on topics like solar and renewable energy for the past several years. Her background spans both eco news outlets and environmental nonprofits.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe