How a Trainload of Toxic Chemicals Derailed Everyday Life in Ohio

Why you can trust us

Why you can trust us

Founded in 2005 as an Ohio-based environmental newspaper, EcoWatch is a digital platform dedicated to publishing quality, science-based content on environmental issues, causes, and solutions.

Every thirty minutes, a Norfolk Southern train passes through East Palestine.

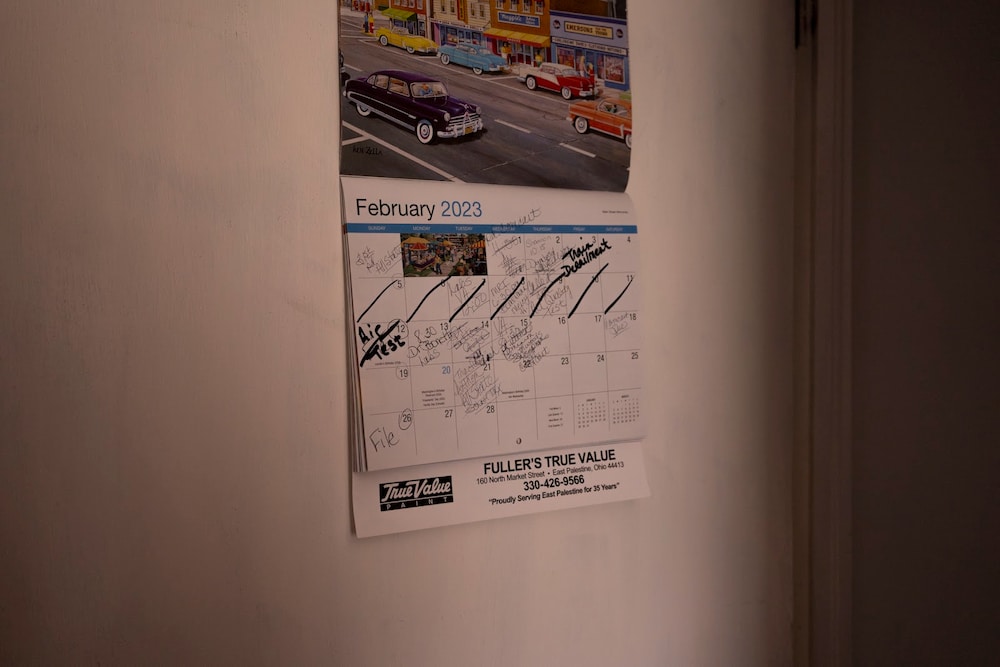

Three months ago, no one in this northeastern Ohio village of just under 5,000 people would have batted an eye at the sight of the long trains passing through. No one would have turned a head at the sound of the train’s whistle as it echoed up North Market Street and down South Market Street toward the farmlands and neighboring communities that surround the village.

But now, three months have passed since a Norfolk Southern train derailed, spilling 20 cars’ worth of hazardous chemicals.

After a controlled burn led to the community evacuating their homes in the village, causing a ripple effect of health concerns, environmental disaster, and an ongoing fight for justice, life will never be the same for the residents who have decided to stay.

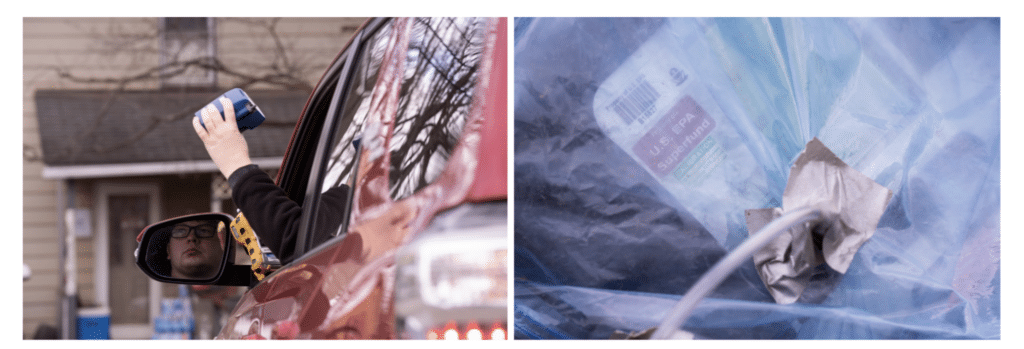

A mile west of the derailment site on Feb. 25, volunteers handed out cases of bottled water in a parking lot. As residents of East Palestine lined up to load their cars, Norfolk Southern trains continued to pass by throughout the day.

A block away, in the parking lot of the First Church of Christ where more volunteers were handing out bottled water, dish cleaner, and other household items, the Ohio Department of Health opened a pop-up clinic for residents to get their vitals checked.

Lori Daughtery, a resident of East Palestine since 2021, was picking up free bottled water from the First Church of Christ when she said she’d had a headache ever since the derailment, and “can’t get rid of this one.” Daughtery said she is prone to chronic migraines, but hadn’t had one for a long time until the derailment happened.

Outside the heart of the village, residents whose homes rely on well water rather than municipal water were still being told to individually test their wells. Rob Runnion, an East Palestine resident and business owner, was waiting for the U.S. EPA to visit his home and test his well water which his wife, two dogs, cat, chickens, and goats, rely on.

On the evening of Feb. 25, Erin Brockovich and her team of lawyers and environmental experts spoke to an auditorium full of people at East Palestine High School following requests from hundreds of East Palestine community members, including lifelong residents Will and Gerri Coblentz.

The Coblentz’s live three blocks away from the site of the derailment, well within the mile radius that was originally evacuated due to a “matter of life and death,” Gov. Mike DeWine of Ohio said at a news conference. Early on the morning of Feb. 4, they woke up to what sounded like an explosion, and watched from their kitchen window as train cars burned — glowing their neighborhood in an orange light.

“We thought all of the houses were on fire, it was a big mushroom cloud,” Gerri Coblentz said.

According to a letter sent from the U.S. EPA to Norfolk Southern on Feb. 10, “cars containing vinyl chloride, butyl acrylate, ethylhexyl acrylate, and ethylene glycol monobutyl ether are known to have been and continue to be released into the air, surface soils, and surface waters.”

When the evacuation was announced, the Coblentz’s left their two dogs and cat behind for three days until they were allowed to return to their home, where they’ve stayed since.

Even though the Ohio EPA said the air and water show no presence of contaminants from the train crash, the Coblentz’s have been drinking bottled water every day. They also decided to get blood tests to detect whether heavy metals from the chemicals are in their body, and they plan on continuing to test their blood periodically.

“That’s a big doubt, not knowing. We don’t know if we’re infected or what we’ve got right now. We’re living normal but down the road, who knows?” Will Coblentz said in an interview at his home on February 25. “Everybody’s got to face it, it’s here. It’s not going away like they said. It’s very emotional for all this stuff to happen.”

“I’m damn mad because that happened right down the street here. And has there been a single person other than CTEH that’s been here to check the air quality of the house, or to check on anyone? No, not a single person,” Gerri Coblentz said.

The Center for Toxicology and Environmental Health (CTEH) is a private contractor that was hired by Norfolk Southern to test water, soil, and air quality in East Palestine.

Weeks after CTEH assured safety to families in East Palestine, including the Coblentz’s, a story published by ProPublica in collaboration with The Guardian revealed that according to several independent experts, the air testing results did not prove their homes were truly safe. Furthermore, the ProPublica article found that CTEH has been accused repeatedly of downplaying health risks in past cases of chemical accidents they’ve been hired to investigate.

In East Palestine, CTEH may be “testing for the wrong chemicals or the detection limits are way too high,” said Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics and chair of the Sierra Club’s National Clean Air Team, in an interview on March 21.

Williams, who has responded to about 30 chemical disasters in the last four years, said the disaster in East Palestine is unlike any she has seen before.

“The strange thing about the Ohio train derailment that really caught my attention is that it is unique that in 2, 3, 4 weeks after the disaster, people are still having acute responses to exposure to something in the air,” she said.

It wasn’t just the derailment itself that surprised Williams, but the coupled choice to burn the chemicals and allow the citizens of the community to return to their homes within the mile radius of the explosion only days later.

“It was the burning of the vinyl chloride that creates and manufactures dioxins and that’s why the EPA is saying ‘we’re not going to test for it.’ They knew they would find it,” Williams said. “Dioxin is the most toxic compound known to man, by far, hands down.”

“I’ve responded to dozens of these disasters now, and I’ve never seen anyone take shape charges and blow up tanker cars of chemicals… they used to do that in the second world war but I haven’t seen that done in this country,” Williams said.

With the United States averaging one chemical accident every two days, according to a map by the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters, Williams cites aging petrochemical infrastructure, and the EPA “refusing to force facilities to do what’s needed to prevent chemical disasters, whether it’s a train derailment or actual chemical manufacturing facility.”

“Chemical disasters are just a part of American life at this point — just like gun violence and just like fentanyl overdoses,” Williams said. “And they’re not likely to reduce in number or in impact.”

Trains continue to run on schedule through the village, cleanup efforts fill the hours throughout the day, and contaminated soil still awaits removal.

According to the U.S. EPA’s latest update on May 18, the excavation of contaminated soil at the derailment site, as well as air monitoring at 23 sites around the village, are continuing.

About 12.8 million gallons of wastewater have been hauled out of East Palestine in total, according to the Ohio EPA’s most recent update on April 20. Additionally, a pile of over 6,000 tons of excavated soil awaited removal from the village, compared to over 31,000 tons that have been removed.

Living alongside hazardous chemicals that remain in East Palestine’s soil below where trains speed by, residents continue to face new health issues and concerns.

River Valley Organizing, a non-profit based in East Liverpool, Ohio, less than 18 miles from East Palestine, has been on the ground meeting with residents since the derailment. Daniel Winston, co-executive director of River Valley Organizing, said that an early Google Form they sent out to community members within the first weeks of the derailment received about 700 submissions from community members reporting various sicknesses and symptoms.

In an interview on May 10, Winston said that community members are reporting such symptoms as skin issues, COPD, lung issues, and even heart issues from people who have never had heart issues in the past. Winston said that while River Valley Organizing can’t confirm that these symptoms are connected, they are working with experts who can help uncover if they are.

“There needs to be long-term monitoring and long-term sampling,” said Dr. Michele Morrone, a professor of environmental health science at Ohio University and the former chief of the Ohio EPA’s Office of Environmental Education, in an interview on February 24.

While the information currently available through air and water quality samples is applicable to acute, short-term exposures, Morrone explained that the true effects that the chemicals in East Palestine may have on people affected by the derailment won’t be known until further down the road.

For residents living in or near East Palestine, Morrone suggests ongoing blood testing which will reveal the effects of the hazardous chemicals that have been suspected to cause community members’ reported acute symptoms, and could prove whether they caused chronic symptoms in the future.

“There’s going to have to be people who are willing to be followed over time,” Morrone said. “Maybe you can measure a chemical today in someone’s blood and maybe it’ll go down tomorrow but you can’t really know what the long term effects are of these measurements until it’s done over a long period of time.”

As the months pass by, Winston urges people and mainstream media to continue talking about East Palestine. “We will be pushing this as hard as we can no matter what,” she said. “The fight is getting harder because we’re so far out. And people think that everything is OK because that’s what has been put out by the EPA and Norfolk Southern.”

On Feb. 21, the EPA ordered Norfolk Southern to conduct all cleanup associated with the derailment and pay all of the costs, which the company has followed, but Winston wants more for the people of East Palestine.

Along with the continued push for Norfolk Southern, and the state and federal governments to respond to River Valley Organizing’s list of five demands created based off community member needs, Winston said that Gov. Mike DeWine desperately needs to call for an official federal disaster in the East Palestine area, and pointed out that DeWine has only until July 3 before the deadline passes.

For the residents in East Palestine and communities across the U.S. that are affected by these chemical disasters, the future remains unclear.

“I hope that we can get answers to what we can do. I hope everybody gets back to normal but that ain’t gonna never happen. Where do we go from here? Who knows? Time will tell. It’s history in the making,” Will Coblentz said.

Subscribe to get exclusive updates in our daily newsletter!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from EcoWatch Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe