USDA Updates Plant Hardiness Map With Many Areas Moving Into Warmer Zones

Why you can trust us

Why you can trust us

Founded in 2005 as an Ohio-based environmental newspaper, EcoWatch is a digital platform dedicated to publishing quality, science-based content on environmental issues, causes, and solutions.

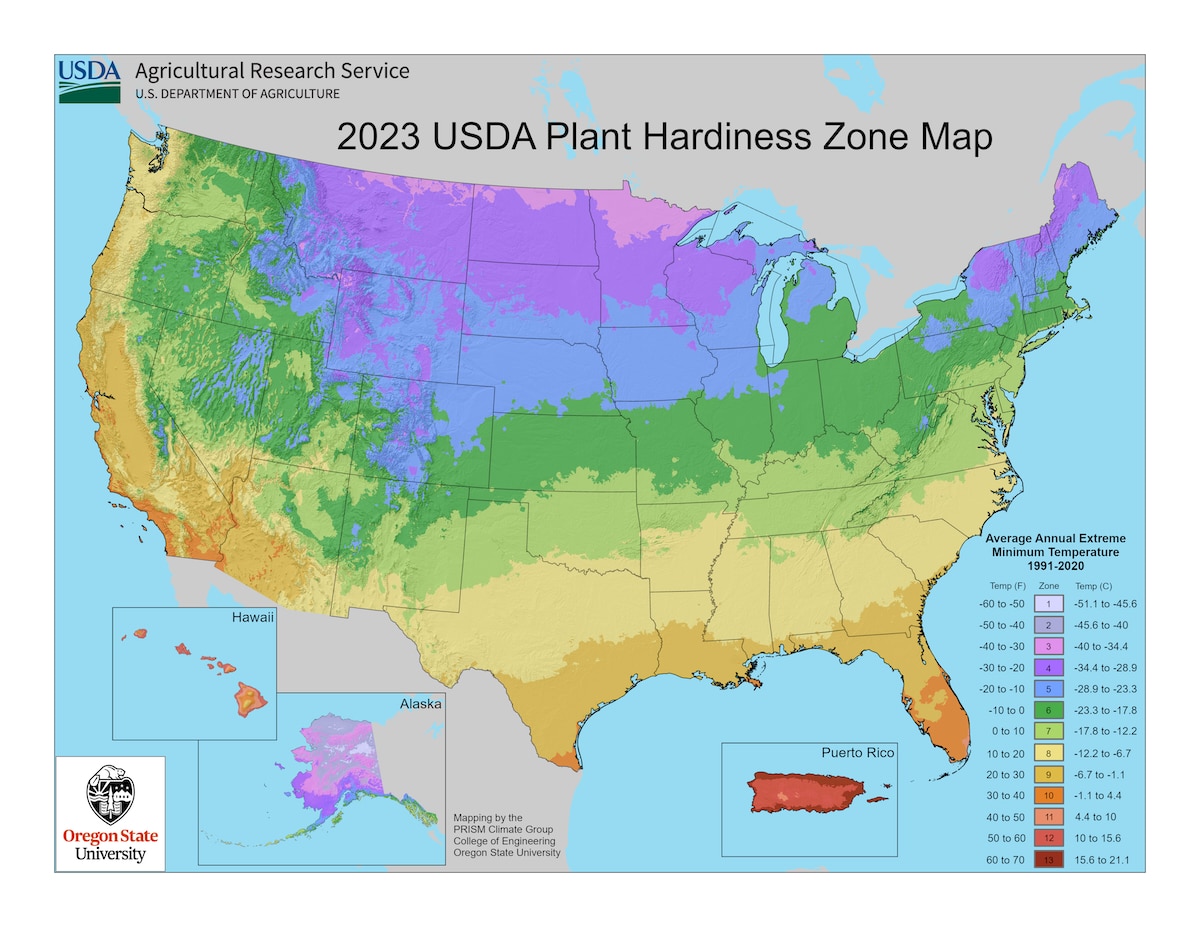

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has updated its Plant Hardiness Zone map, a map of the U.S. that helps gardeners decide what plants will grow best in their local areas, based on average annual extreme minimum winter temperature. The updates show an average of 2.5°F warmer across the contiguous U.S. compared to the previous map, which was published in 2012.

Experts used used a 30-year period of data, from 1991 to 2020, to develop the latest edition. They also pulled data from 13,412 weather stations, an increase from 2012, when experts used data from 7,983 weather stations. This increase in stations, combined with more advanced technology, has led to the most comprehensive and accurate Plant Hardiness Zone map to date.

The USDA noted that changes in climate are typically based on trends from 50 to 100 years’ worth of data, not 30 years, so the USDA doesn’t consider zone changes in the map to be evidence of climate change. Further, the variables that were used to develop the map can change significantly.

“Changes to plant hardiness zones are not necessarily reflective of global climate change because of the highly variable nature of the extreme minimum temperature of the year,” a USDA spokesperson told NPR.

But the map did have a shift of about one quarter-zone warmer throughout the country compared to the 2012 map. As Axios reported, parts of the Midwest and Great Plains had some of the greatest shifts into warmer zones.

“Overall, the 2023 map is about 2.5 degrees warmer than the 2012 map across the conterminous United States,” Christopher Daly, director of the PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University and lead author of the map, said in a press release. “This translated into about half of the country shifting to a warmer 5-degree half zone, and half remaining in the same half zone. The central plains and Midwest generally warmed the most, with the southwestern U.S. warming very little.”

The shifts mean that many people around the U.S., especially where there were significant zone shifts, can more successfully grow plants that may be new to them. Although many gardeners are interested in the possibility of growing different types of fruits, veggies and other plants, there are also concerns about long-term warming.

“We’re excited, but in the back of our minds, we’re also a little wary,” said Megan London, a gardening consultant based in Hot Springs, Arkansas, as reported by NPR. “In the back of our mind, we’re like, ah, that means things are warming up. So what does this mean in the long run?”

Although the specific map changes haven’t been attributed to climate change, Daly and other experts said that the zones could gradually shift north in the long-run because of global warming.

Subscribe to get exclusive updates in our daily newsletter!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from EcoWatch Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe