By Jeff Turrentine

I used to live in a hilly, temperate corner of the American west, right near the banks of a meandering river. On late-evening walks with my two dogs, I would routinely encounter all manner of economy-size mammalian wildlife: skunks, raccoons, opossums, coyotes. Sightings of a mountain lion in the area had occurred more than once, though my dogs and I were perfectly happy never to have chanced upon him. During the day, it wasn’t unusual to see red-tailed hawks or turkey vultures circling overhead, or rigid V-formations of migrating Canada geese, or even the occasional egret or blue heron swooping down as it made its descent to its riparian home.

Oh, wait, I left out an important detail: My dogs and I were walking in the heart of Los Angeles—within earshot of the considerable traffic noise emanating from the I-5 Freeway, about 15 minutes from downtown as the crow (or the turkey vulture) flies. We were proximate, too, to Griffith Park, which at more than eight square miles is one of the largest urban parks of its kind, as well as one of the least developed. Our local mountain lion, the rather ignobly named P-22, called Griffith Park home; he’s still there, in fact, roaming the hills and doing what mountain lions do, minding his own carnivorous business while largely (if not totally) steering clear of awkward interactions with humans and the built environment.

I couldn’t help but think of P-22, and of my old wild stomping ground, when I learned that researchers from the National Park Service had recently installed cameras along 30 miles of the Los Angeles River and its tributaries. The LA River Wildlife Camera Project aims to document the abundance of fauna skulking, skittering and waddling along this waterway, to better understand their relationship to the river and—importantly—to increase public awareness of urban wildlife, in hopes of reducing instances of human-animal conflict.

Los Angeles is far from unique as an urban haven for unexpected forms of wildlife. Berlin is currently home to more than 3,000 wild boars, which unabashedly forage in parks and front yards. In Mumbai, one of the world’s most densely populated cities, more than 40 leopards wander the streets in and around Sanjay Gandhi National Park, often applying their instinctive predatory skills to the city’s sizable population of feral dogs. Coyote sightings are becoming more and more common in New York and Chicago. In March, John McPhee, the longtime New Yorker contributor, wrote colorfully of his fascination with the estimated 2,500 black bears that live (and sometimes steal cupcakes out of parked cars) in his home state of New Jersey. If you’ve ever visited Austin, Texas, and not been bitten by a mosquito, you can thank the 1.5 million Mexican free-tailed bats that live beneath the Congress Avenue Bridge downtown.

As our civilization encroaches further and further into wildlife habitat, we find ourselves sharing space with more and more creatures that we don’t expect to find in our midst. But to paraphrase one commenter to a YouTube video featuring a mama bear and her cubs frolicking in a backyard swimming pool: They’re not in our backyards, we’re in their front yards. When we build on wildlife habitat, the land doesn’t suddenly become “ours” and no longer “theirs.” It becomes shared. And as the most recent arrivals, we humans have an obligation—a moral and ecological imperative, you might even say—to understand the ways, habits and needs of the communities that we’re asking to join.

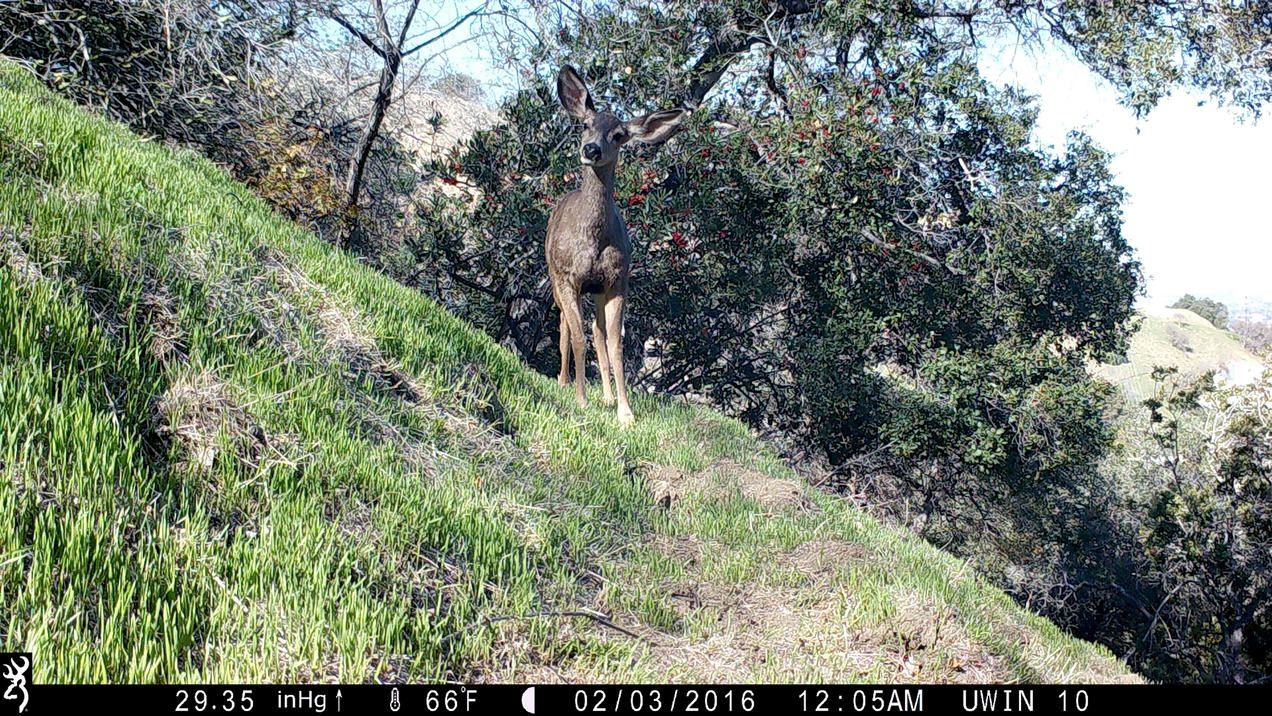

A deer seems to spot the camera along the Los Angeles River.National Park Service

In Los Angeles, the LA River Wildlife Camera Project is being conducted in partnership with the larger Urban Wildlife Information Network, a Chicago-based consortium of scientists and researchers dedicated to helping cities “understand the ecology and behavior of their own wildlife species … why animals in different cities behave differently, and what patterns hold true around the world.” Images of animals caught on camera will be uploaded to Zooniverse, a platform for crowdsourced research where volunteers can share ideas and engage in citizen-science scholarship, which often proves to be of immense value to academic researchers.

The LA River, an ecologically vital yet troubled waterway, is a prime subject for such study. At 51 miles long, the river begins in the San Fernando Valley north of the city and winds its way through neighborhoods industrial, residential and semi-rural before finally emptying into the Pacific Ocean at Long Beach. Environmentalists, political leaders, scientists and civil engineers recently embarked on an ambitious plan to restore it, a major component of which will entail reconnecting the channelized waterway to its historic tributaries, wetlands and floodplains—i.e., to historic wildlife habitat. Initiatives like the Camera Project have the potential to spur public support and private funding, because through compelling photographic evidence, the essential relationships among local people, local resources, and local wildlife are made clear.

As I learned on those late-night walks with my dogs: You’re never really alone in the big city, even when there are no other people around. The more we learn about the animals within our shared communities, the more we learn about what they—and we—need in order to coexist harmoniously and sustainably. And that’s about as good a definition of neighborliness as you’re ever likely to come across.

Reposted with permission from our media associate onEarth.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe