We may tend to think of evolution as something that happens slowly over millions of years, but that’s not always the case. When a population of a particular species changes, there can be a variety of possible causes, including climate change or human pressures on a particular ecosystem, such as overfishing.

When a species changes more quickly than traditional views of natural selection would historically allow, it is called “rapid evolution” or “evolution in action.” These sped-up evolutionary processes are due to “the interplay of ecology and evolution as a dynamic interaction in both directions and on contemporary timescales,” which “confirms the paradigm that demographic and evolutionary changes are ultimately entangled,” according to a 2014 study published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

A new study considers the case of the shrinking of wild Atlantic salmon in Northern Finland’s River Teno, where overfishing was considered as a possible cause for the notable change in the salmon’s size. However, the study has demonstrated that the shrinking of this particular population of fish might have another more indirect cause.

The study, “Rapid evolution in salmon life history induced by direct and indirect effects of fishing,” was published last month in the journal Science.

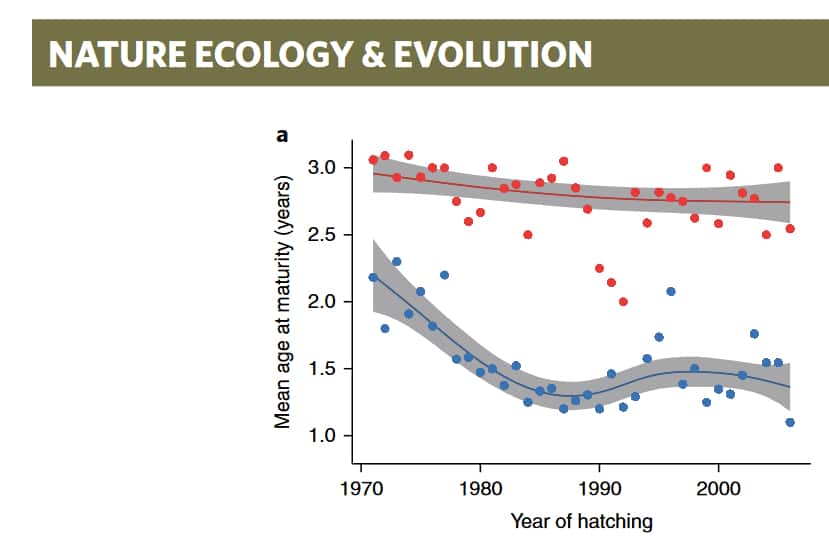

“Our earlier research had shown that the age at which salmon were maturing in this river was getting younger, and consequently also the size of salmon that are spawning was getting smaller, showing ‘evolution in action.’ Important for demonstrating rapid evolution, there were also changes in their DNA at a gene known to be linked with maturation size and age,” said Craig Primmer, a professor in the Organismal and Evolutionary Biology Research Programme at the Institute of Biotechnology at the Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science, as Natural Resources Institute Finland reported.

The shrinking of the River Teno wild salmon is thought to be the result of the commercial fishing of capelin (Mallotus villosus), a small fish found in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans.

Using genetic methods, Finnish scientists discovered how changes in salmon fishing, in addition to the commercial fishing of capelin — one of the favorite foods of wild salmon — might be related to the shrinking of the wild Atlantic salmon population.

Some of the capelin caught by commercial fishers is used as fishmeal to feed aquaculture salmon, and overfishing of capelin could be indirectly affecting the wild salmon, the study suggests.

“The aquaculture industry has made important progress in finding alternative protein sources for aquaculture fish feed, and our study suggests that these efforts have not been in vain, as it seems capelin harvest may affect wild salmon populations,” said Primmer, as reported by Natural Resources Institute Finland.

Alternative sources of protein and the use of fish parts from processing plants that would normally go to waste are helping to reduce the use of wild fish for fish feed.

“Different kinds of plant-based proteins are being used more and more. Also waste parts from other kinds of fish processing are being used in order to decrease the amount of wild fish used in aquaculture (and other domestic animal feed),” Primmer told EcoWatch in an email.

The researchers found that another more direct cause of the increase of smaller salmon is likely the use of salmon weir by local fishers.

“We found that a special net type, a salmon weir, that accounts for [the] majority of net catches, is capturing predominantly smaller fish, although net fishing is often assumed to catch larger fish,” said Jaakko Erkinaro, a research professor at Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Natural Resources Institute Finland reported.

Indigenous Sámi fishers told the researchers that the smaller mesh size of the salmon weir, which is used in shallower waters later in the season, increases the catch of smaller fish.

And the spawning populations of small, early maturing fish have grown as weir fishing has decreased.

The decrease in weir fishing is primarily because of restrictions imposed by the governments of Norway and Finland, Primmer told EcoWatch.

In order to tell which of these influences was responsible for the rapid evolutionary changes happening in the River Teno wild salmon population, lead author of the study Dr. Yann Czorlich said the researchers needed to connect annual differences in the variation of salmon DNA with yearly environmental changes and influences caused by humans.

“We gathered literally millions of data-points about factors, including yearly water temperature, salmon fishing effort, and commercial fisheries catches of the fish salmon eat in the ocean, and compared them with our data on DNA changes in our 40-year time series,” said Czorlich, as reported by Natural Resources Institute Finland.

To do this, the scientists looked at samples of scales from salmon over a period of 40 years and were able to find that a gene variation for salmon size and reproduction age was influenced by various fishing methods. They used the scales to obtain the DNA and to figure out the salmon population’s age distribution. Maintained by Natural Resources Institute Finland, the archive contains over 150,000 scale samples from individual salmon collected since the 1970s.

Decrease in salmon population size could be seen as an indicator that the fish would be less resilient to environmental changes in the future, but it could also be viewed as evidence that the salmon are adapting.

“Variation in age at maturity is one of the key life-history traits that results in life-history strategy variation in the population. So generally smaller size likely means there will be less life history variation in general, which means there may be less of a buffer to deal with future environmental changes. Another way to say this more generally is that reduced life history strategy variation likely results in less biological resilience in the population,” Primmer told EcoWatch. “On the other hand, we have been able to show that this change is likely due to evolutionary adaptation, so that indicates that the change is in the direction towards the life-history strategies that are more optimal for the current environmental conditions, so in a way, the change can be considered a good thing in that the population is adapting.”

However, the size of the Teno River salmon seemed to have stabilized in the 1990s.

“The largest decrease was earlier in the time series, especially in males… But from the 90s on, male size has stabilized (but is still small),” Primmer said.

The shrinking of the population of the Teno River wild salmon, rather than the shrinking of their size, is currently affecting a traditional food source for the indigenous Sámi people.

“Food source issues are a combination of size and abundance. Size per se does not necessarily cause problems if fish are abundant, but currently they are not, so it is affecting the traditional food availability of indigenous Sámi from the Teno river valley,” Primmer told EcoWatch. “Further, salmon fishing is a source of livelihood for some Sámi and other locals via fishing tourism (people travel very far to this remote region to try and catch big salmon, and locals act as guides), so reductions in the frequency of large salmon have negative effects on this.”

Primmer indicated that, since fishing regulations have not improved the numbers or size of the Teno River salmon, solutions need to extend farther than the salmon, the river and even Finland itself.

“The fishing regulations that are in place appear to have reduced the selection pressure in recent decades, i.e. they have been doing what they are supposed to do, but as neither abundance nor size have improved, it suggests that more needs to be done. Our results show that the solutions may be quite challenging and complex, as regulating fishing of salmon in the river seems to be only one part of the problem: also fishing of other species at sea, by a range of other countries, seems to be affecting Teno salmon size. But at least we now know that a focus on what happens in the ocean is also needed,” Primmer said.

An approach that takes into consideration traditional fishing by the indigenous Sámi people, businesses based on fishing tourism and restrictions meant to protect fish populations is a difficult balancing act.

“What is best for people will depend on who you ask — as a researcher I could say that ‘stop all fishing’ is the safest way, but these stocks have been fished for millennia by indigenous Sámi, who are now struggling to pass their knowledge of traditional fishing methods to the next generation due to the strong restrictions, and then there are others whose fishing tourism businesses are struggling, so it is a very complex question to answer,” Primmer told EcoWatch. “Ideally, targeted, well focused, restrictions that still allow some fishing that does the least damage would be the best strategy, and I hope our research results are able to support that.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe