Large Swath of Texas Oil Patch Rapidly Sinking and Uplifting, Study Finds

A massive sinkhole in Winkler County, Texas. Google Earth

West Texas is already home to two giant

sinkholes near the town of Wink caused by intensive oil and gas operations. Now, according to an unprecedented study, the “Wink Sinks” might not remain the last in the region.

Geophysicists at Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas have found rapid rates of ground movement at various locations across a 4,000-square-mile swath around the two sinkholes. This area is known for processing extractions from the oil-rich

Permian Basin.

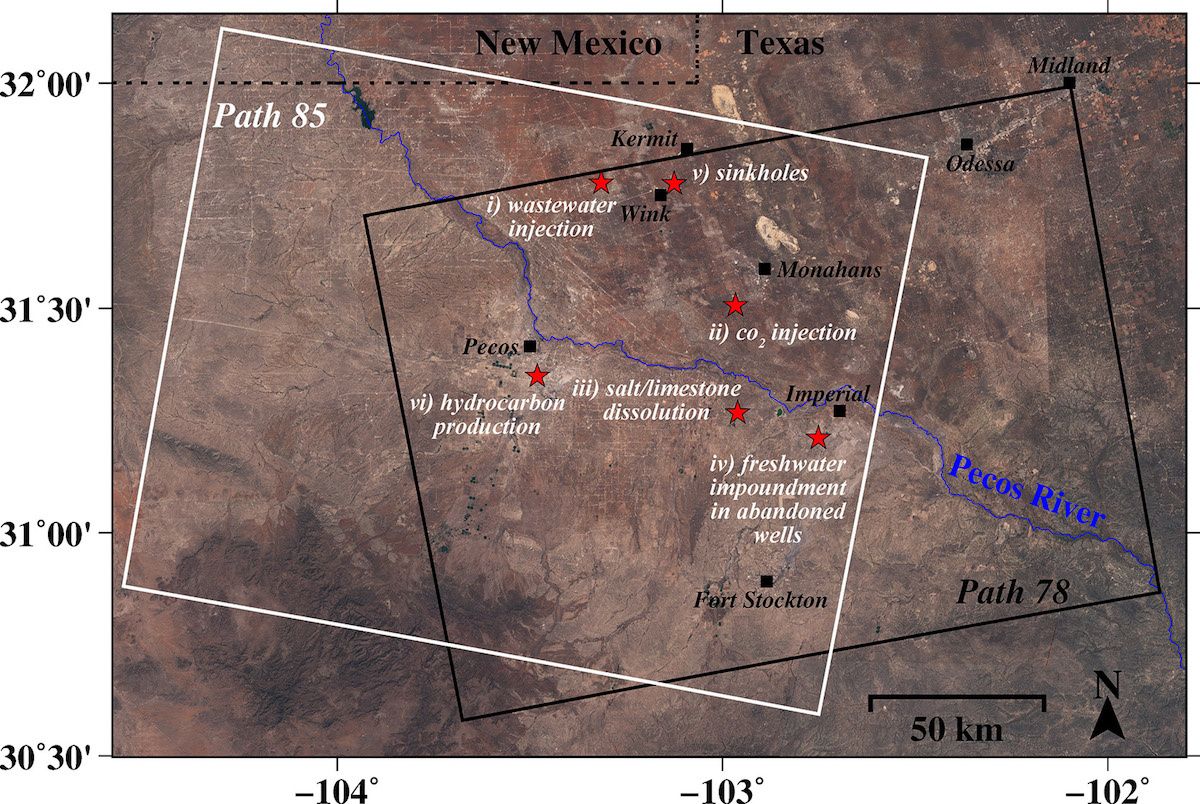

The scientists made the discovery after analyzing radar satellite imagery taken between November 2014 and April 2017. Combined with oil-well production data from the Railroad Commission of Texas, the researchers concluded that the area’s sinking and uplifting ground is associated with decades of oil activity and its effect on rocks below Earth’s surface.

“Based on our observations and analyses, human activities of fluid (saltwater, CO2) injection for stimulation of hydrocarbon production, salt dissolution in abandoned oil facilities, and hydrocarbon extraction each have negative impacts on the ground surface and infrastructures, including possible induced seismicity,” the

study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, says.

Two massive sinkholes about a mile apart from the other in West Texas. The first “Wink Sink” opened up in 1980 and is about as wide as a football field. The second and larger hole opened in 2002 and stretches around 900 feet at the widest point.Google Earth

One location saw as much as 40 inches of movement over the past two-and-a-half years, the geophysical team found.

“The ground movement we’re seeing is not normal,” said co-author

Zhong Lu, a professor in the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at SMU. “The ground doesn’t typically do this without some cause.”

The latest findings build on the

team’s 2016 report that revealed the existing “Wink Sinks” are expanding and new ones are forming.

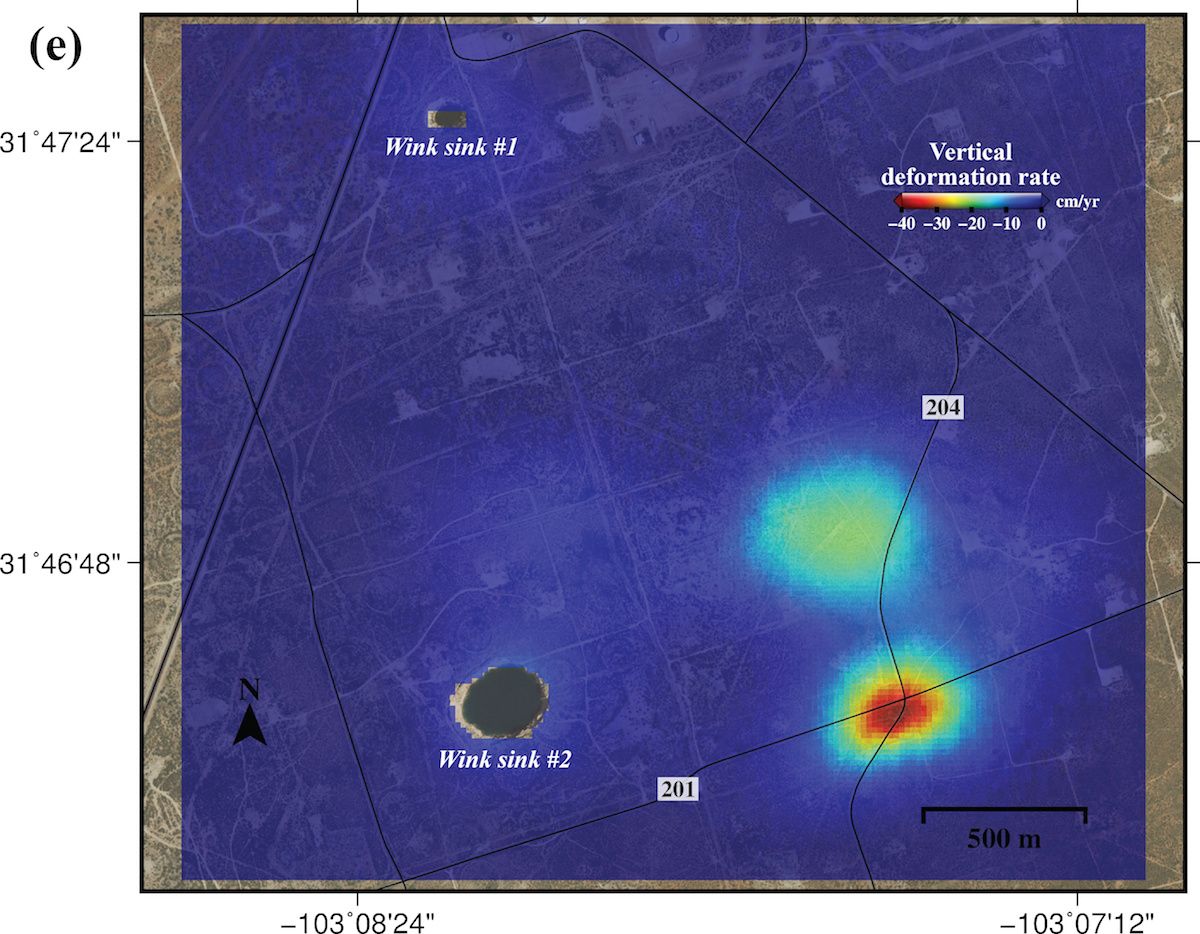

Radar detected significant ground sinking a half-mile east of the huge Wink No. 2 sinkhole, where there are two subsidence bowls, one of which has sunk more than 15.5 inches a year. The rapid sinking is most likely caused by water leaking through abandoned wells into the Salado formation and dissolving salt layers, threatening possible ground collapse.

Zhong Lu / Jin-Woo Kim / SMU

The region is populated by four counties and six towns, in addition to a vast network of oil and gas pipelines and storage tanks.

“These hazards represent a danger to residents, roads, railroads, levees, dams, and oil and gas pipelines, as well as potential pollution of ground water,” Lu warned. “Proactive, continuous detailed monitoring from space is critical to secure the safety of people and property.”

The researchers suggested that ground instability could be occurring in areas outside the ones surveyed.

“Our analysis looked at just this 4,000-square-mile area. We’re fairly certain that when we look further, and we are, that we’ll find there’s ground movement even beyond that,” said study co-author and research scientist

Jin-Woo Kim.

“This region of Texas has been punctured like a pin cushion with oil wells and injection wells since the 1940s and our findings associate that activity with ground movement.”

SMU geophysical team found alarming rates of ground movement at various locations across a 4,000-square-mile area of four Texas counties. Zhong Lu / Jin-Woo Kim / SMU

In response to the study, Todd Staples, president of the Texas Oil & Gas Association, told

Dallas News: “Subsidence and uplift are found in many areas and the variety of conditions described in the report obviously require additional research to properly reflect on the situations.”

“We look forward to reading the report in depth and will continue to produce oil and natural gas responsibly and safely, and in compliance with science-based rules and regulations.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe