By Jocelyn Timperley

The UK could soon see its first use of hydraulic fracturing since 2011.

The controversial technique for extracting shale gas and oil, known as fracking, is set to be used by the end of this year at a site in Fylde, Lancashire, owned by UK company Cuadrilla. The firm said it hopes to start drilling within weeks.

But how close is the UK to shale gas production on a large scale? And what would the carbon impacts of this be?

Carbon Brief breaks down the key climate questions facing fracking in the UK.

Has There Been Any Fracking in the UK?

Yes, but not since two tremors near Blackpool were caused by Cuadrilla’s fracking operations at its Preese Hall site in 2011.

Fracking involves pumping water mixed with chemicals at high pressure into a well, in order to fracture the surrounding rock and let oil or gas escape. It has been used in the oil industry since the mid-20th century.

However, the technique has only recently become widespread in onshore gas extraction, after advances in horizontal drilling allowed it to be applied to shale resources.

The process began attracting attention in the UK when the government granted the first onshore exploratory licenses for shale gas in 2008.

After the Blackpool tremors were identified in late 2011 as likely to have been caused by fracking, the UK’s then-Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) put a moratorium on the practice, until it was better understood.

This was lifted a year later by then-energy secretary Ed Davey, who said exploratory fracking for shale gas could resume, subject to new controls to minimise seismic risks.

The UK already uses small quantities of shale gas and oil. Anglo-Swiss firm Ineos began importing US shale ethane in September last year, for use in the chemical industry. The Isle of Grain terminal on the Thames estuary took the UK’s first delivery of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from US shale in early July.

However, the North Sea still produces the vast majority of UK gas supplies. The UK is not expected to be able to compete for U.S. LNG with Asian markets, where prices are higher.

US LNG exports are growing, following a string of approvals granted by the Obama administration. As a result, the U.S. is expected to become a net exporter of gas later this year. Increasing fossil fuel exports is part of U.S. President Donald Trump’s plan to achieve what he calls “energy dominance.”

Is Energy ‘Dominance’ the Right Goal for U.S. Policy? https://t.co/THAKlTSlYR @foeeurope @Green_Europe

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) July 4, 2017

When Will Fracking Next Take Place?

Cuadrilla expects to conduct exploratory fracking later this year at its Preston New Road site in Lancashire, the firm tells Carbon Brief.

Planning consent for Cuadrilla to explore for shale gas at the site using fracking was granted by the government in October 2016, when it overruled local councillors’ rejection.

Cuadrilla started work at the site in January, with the main drilling rig brought on site at the end of July. A spokeswoman for the firm tells Carbon Brief it plans to begin drilling horizontal wells into shale rock this month, with fracking beginning towards the end of the year.

However, the spokeswoman adds that Cuadrilla is unsure how long the process will take, since this is the first time horizontal wells have been drilled into the UK’s shale rock. (The Preese Hall site only had a vertical well). It, therefore, cannot say exactly when the first fracking will take place, she said.

Cuadrilla had originally planned to begin fracking by the third quarter of this year. An ongoing protest at the site may be delaying development. Since January, anti-fracking protesters have maintained a continuous presence outside the site.

A drilling rig owned by the firm was vandalized last month at a facility near Chesterfield, where it was being stored, while Cuadrilla recently breached its planning permission by delivering a drilling rig overnight, apparently to evade the protestors.

If Cuadrilla does use fracking at the site, it would be the first time in the UK since the 2011 moratorium was put in place.

Cuadrilla also has an application for exploratory fracking at a second Lancashire site, Roseacre Wood. A public inquiry on the application is set to take place in April 2018, after a legal challenge by protesters failed to stop it going ahead.

It’s worth emphasizing that Cuadrilla’s projects are at the exploratory stage and are not yet producing shale gas. However, Cuadrilla’s spokeswoman tells Carbon Brief that gas from its site will be “fueling Lancashire homes and businesses mid next year.” This statement is based on Cuadrilla already having planning consent for an extended flow test, that would send small quantities of gas into the grid. Again, this would fall short of full-scale production.

Where Else Are Firms Planning to Use Fracking?

At least five other firms are planning to explore for shale gas in the UK. The map below shows where they hope to operate.

Note that fracking will not be used at all the sites shown on the map. Cuadrilla has said it will not need to carry out fracking at its oil exploration well at Balcombe, for example, since the rock is already naturally fractured. (Note that it has no plans to continue exploration at this site, having decided to focus on shale gas extraction in Lancashire).

The map includes Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road and Roseacre Wood sites in Lancashire, the only ones for which the firm is currently seeking permission to carry out fracking.

Also of note are three sites near Sheffield, licenced to Ineos Shale, a UK-based subsidiary of Anglo-Swiss chemical giant Ineos, which aims to drill test wells to assess the suitability of the sites for extracting shale gas. In July, Ineos Shale won a broad pre-emptive injunction that will put protesters in contempt of court if they obstruct its shale operations.

Meanwhile, last month Third Energy submitted its final plans to start fracking for shale gas at its Kirby Misperton site in North Yorkshire. It was granted planning permission for the site in May 2016.

This plan still needs to undergo a technical assessment from the Environment Agency and requires approval from the government’s Oil and Gas Authority (OGA). A spokesman for Third Energy tells Carbon Brief it hopes to begin fracking this year.

How Much Shale Gas Does the UK Have?

The British Geological Survey (BGS) said the UK has large amounts of shale hydrocarbons below its surface. However, the precise distribution is not yet well known and there remains significant uncertainty over how much is extractable.

The BGS has examined how much shale resources there are in several areas of the UK (see video below). Its central estimates for these are:

- More than 1,300 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of shale gas in the Bowland-Hodder shale in Lancashire;

- Around 4.4 billion barrels (bbl) of shale oil in the Weald basin in Sussex, but no significant gas resource;

- A further 1.1bbl of shale oil in part of the Wessex basin, near the Weald basin and;

- Some 80tcf of shale gas and 6bbl of shale oil in the Midland Valley of Scotland.

Two things are worth emphasising here. First, these are central, fairly rough estimates. The BGS’s range for the Bowland-Hodder shale, for example, is a lower limit of 822tcf and upper limit of 2281tcf.

Most importantly, though, these are calculations of the total resources of shale. Only a fraction of this will be commercially extractable reserves, depending on the cost of UK operations and the international market price of gas.

The BGS said it is too early to know what proportion of UK shale resources are recoverable, although it said U.S. recovery factors are typically around 10 percent. Note that shale firms often argue they need to begin drilling before they can understand how much of the UK’s shale gas is extractable.

The UK uses around 3tcf of gas each year. Assuming a 10 percent recovery rate and the BGS’s central estimates, the UK has 138tcf or around 46 years worth of technically extractable shale gas.

It’s worth noting a 2013 assessment by the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated a far lower technically recoverable resource in the UK of 26tcf, equivalent to nine years of current UK gas use.

A 2010 BGS estimate for the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) put the “total recoverable reserve potential” in the UK even lower, at just 5.3tcf. This is less than two years of use.

Research by UK-based commercial oil and gas consultancy the Energy Contract Company (ECC), published in 2012, put technically recoverable shale gas far higher than this, at 40tcf, around 13 years worth.

Meanwhile, in 2013 the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST) estimated a potentially recoverable resource of 64-459tcf in the Bowland shale formation alone. This figure is based on a range of recovery rates of 8-20 percent.

There are currently no official reserve estimates. As POST observed, UK reserves could be anywhere from “zero” to “substantial.” It said: “To determine reliable estimates of shale gas reserves, flow rates must be analyzed for a number of shale gas wells over a couple of years.”

Where Have Oil and Gas Licenses Been Granted?

There are 137 ongoing oil and gas licenses granted in UK government licensing rounds. The most recent, the 14th onshore licensing round, was launched in 2014, the first since 2008. This resulted in another 93 licenses being given to 22 successful applicants in 2015.

It’s worth noting that these licenses do not give permission for operations, but rather grant exclusivity to licensees for exploration and extraction of any hydrocarbon, including for shale gas and oil within the area.

A spokesperson for the government’s Oil and Gas Authority (OGA), told Carbon Brief:

“Subject to planning permission, relevant scrutiny and other permits, a proposal for shale exploration could progress on any extant onshore license, not just ones issued in the 13th or 14th rounds when the potential was first identified.”

However, 63 of the 93 licenses granted in 2015 are in areas of potential shale exploration, according to investigative website Drill or Drop.

The video below shows the areas of shale gas and oil potential in the UK, based on maps from the OGA.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BX2l27El754/

Which parts of the UK are open to fracking? Animation by Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief. Maps from the Oil and Gas Authority. Music: ketsa (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Sound effect: dshogan (CC BY-NC 3.0).

The maps show, in turn:

- Shale oil and gas study areas. Areas which have been surveyed by the British Geological Survey (BGS), a public sector research body, to see if they might contain extractable shale hydrocarbons. These are the main areas that could be used to produce shale oil or gas in the UK, according to the BGS. There are other minor areas that it has not yet studied.

- Shale prospective areas. Areas of shale rock that the BGS has identified as containing potentially extractable shale gas or oil.

- Current oil and gas licenses. All ongoing licenses in the UK for onshore oil and gas extraction, including conventional and non-conventional resources, such as shale. Licenses specifically related to shale resources were first awarded in 2008 and 2015, during the government’s 13th and 14th licensing rounds.

- Oil and gas licenses awarded in 2015. Blocks awarded in the government’s 14th licensing round, which launched in 2014. This was the most recent offer of onshore oil and gas licenses and only the second to explicitly include shale resources.

- Total area made available for license in 2014. All areas opened for bidding in the 14th licensing round. This covers approximately two fifths of the UK.

It’s worth emphasizing that some of the licenses shown in the map above are for firms that intended to explore for conventional oil or gas, rather than shale gas. Edward Hough, a geologist from the BGS, told Carbon Brief:

“Operators may explore for shale gas and also a conventional source of hydrocarbon under the same license. In some parts of the country, shale targets may underlie conventional hydrocarbon reservoirs; as such, it’s not possible to put a figure on how many licenses are for shale versus conventional oil and gas.”

In addition, companies holding licenses still need to go through planning applications to gain consent for drilling, with only a couple of companies currently at this stage in just a few locations (see first map above).

Does the UK Need Shale Gas?

While it’s important to consider how much of the UK’s shale gas is recoverable, perhaps the more pertinent questions are how soon it could start to flow and if it is needed.

This is crucial to the question of whether shale gas production can be ready in time to replace the UK’s rapidly falling coal use, the main way it could substantively cut UK greenhouse gas emissions (see below).

According to National Grid’s most recent Future Energy Scenarios, UK gas production fell to 35 billion cubic metres (bcm; 1.2tcf) in 2016, a third of its level in 2000. This fall has been offset by a 20 percent fall in demand, with imports making up the difference. Similarly large falls in conventional UK gas production are expected over the next 30 years, National Grid said.

This fall in production could be offset by cutting demand further, by importing more gas, by producing domestic shale gas or a combination of all three.

To explore these options, National Grid lays out four scenarios, with shale gas included in the two with reduced climate ambition. It’s worth highlighting that these scenarios are not forecasts of what is most likely to happen, but rather potential paths, which can also serve as warnings. Only one of the scenarios meets the UK’s legally-binding carbon targets.

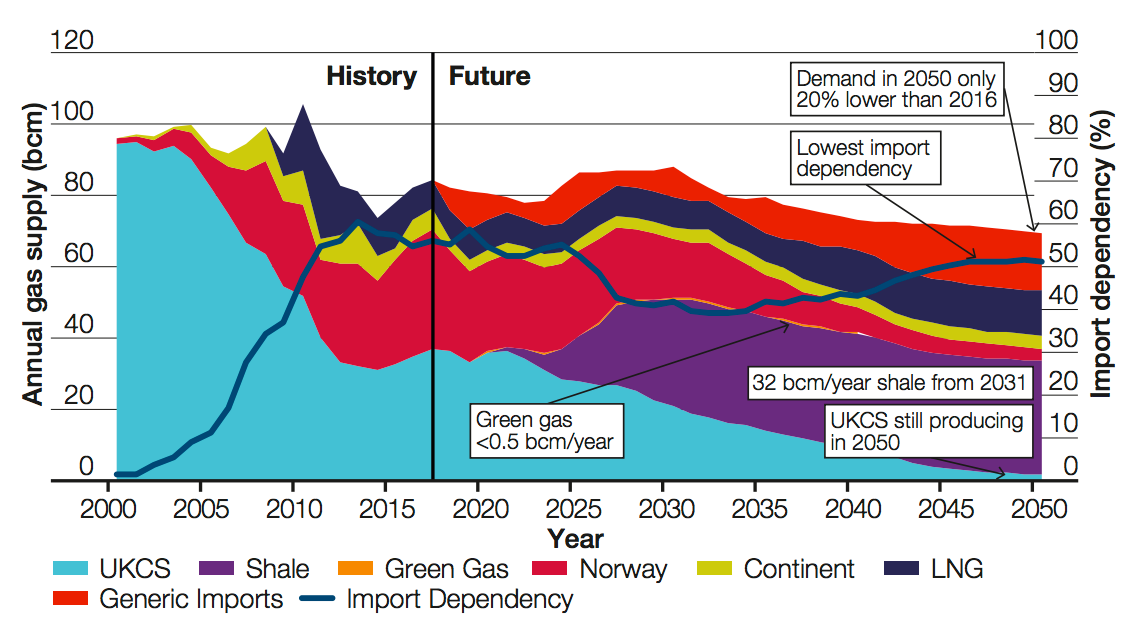

Its “consumer power” scenario has high gas demand and a focus on domestically produced supplies. Shale production begins around 2020, ramping up to 32bcm (1.1tcf) per year from 2031. Total annual gas use in 2050 sits at 70bcm (2.5 tcf), only 20 percent lower than in 2016.

Annual UK gas supply by source (billions of cubic meters, left axis) and the share of supplies that are imported (percent, right axis) in the Consumer Power scenario. UKCS is North Sea supplies from the UK continental shelf. Continent is mainly the Netherlands. LNG is liquefied natural gas delivered by ship. Green gas includes biogas derived from anaerobic digestion. Source: National Grid Future Energy Scenarios 2017.

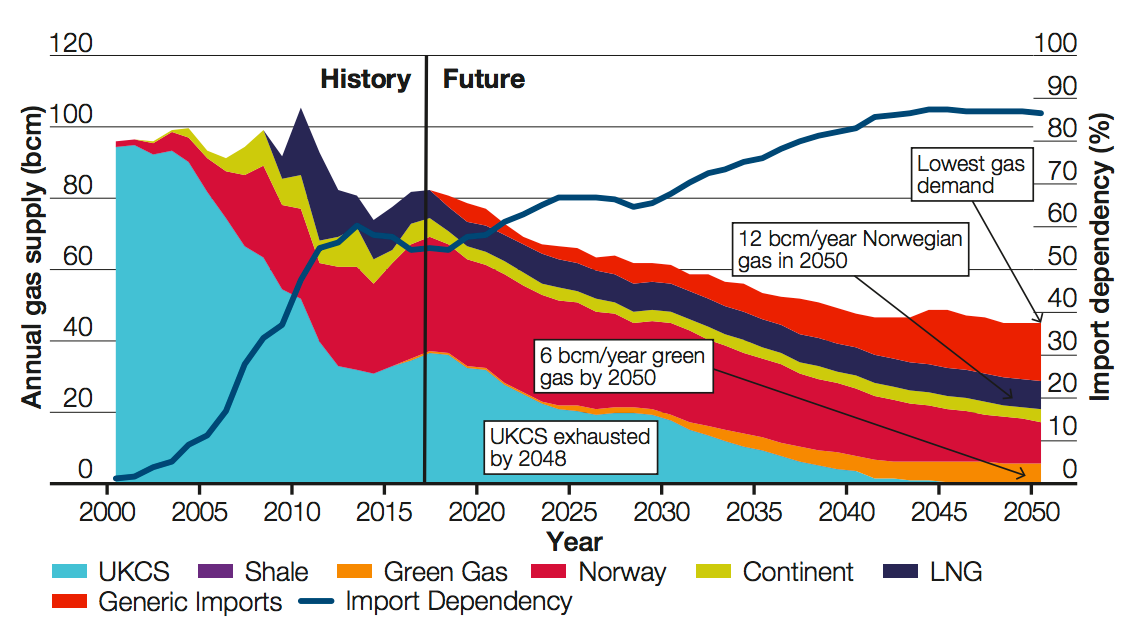

In National Grid’s legally compliant “two degrees” scenario, investment in renewable technologies, including “green gas,” as well as efforts to cut demand, leave no incentive for shale gas development. Annual gas supply in 2050 falls to 40bcm (1.4tcf), some 50 percent below 2016 levels. This scenario leaves the UK more dependent on gas imports, however.

Annual UK gas supply by source (billions of cubic meters, left axis) and the share of supplies that are imported (percent, right axis) in the Consumer Power scenario. UKCS is North Sea supplies from the UK continental shelf. Continent is mainly the Netherlands. LNG is liquefied natural gas delivered by ship. Green gas includes biogas derived from anaerobic digestion. Source: National Grid Future Energy Scenarios 2017.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) has also assessed the future for gas within UK carbon targets. As Carbon Brief reported at the time, it said that gas use should fall by around 50 percent in 2050, rising to a 80 percent fall if carbon capture and storage is not available.

It’s worth noting that the CCC has also said UK heating must be virtually zero-carbon by 2050, with options to reach this goal including district heating schemes, low-carbon hydrogen in the gas grid (see below) and electric heat pumps.

What Does Shale Gas Mean for Greenhouse Gas Emissions?

A 2013 report co-authored by the late Prof David MacKay, then chief scientist to the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), found UK shale gas would have much lower emissions than coal, slightly lower emissions than imported liquified natural gas (LNG) and higher emissions than conventional gas.

Like the CCC, this report emphasised the need to ensure UK shale gas production did not lead to an overall increase in international supply and demand for gas.

The authors warned that the “production of shale gas could increase global cumulative GHG emissions if the fossil fuels displaced by shale gas are used elsewhere.”

They concluded: “The view of the authors is that without global climate policies (of the sort already advocated by the UK) new fossil fuel exploitation is likely to lead to an increase in cumulative carbon emissions and the risk of climate change.”

Advocates have argued that shale gas could help to cut greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the use of coal. This might be possible as long as fugitive methane emissions remain below a certain level, often calculated at around 3 percent.

In practice, however, the UK is unlikely to be able to replace coal with domestic shale gas, given coal is being phased out of the power sector by 2025 and is expected to fall to very low levels well before then.

This leaves the small potential emissions advantage of domestic shale gas over imported LNG.

The CCC says that onshore oil and gas extraction, including fracking, is incompatible with the UK’s climate targets unless it can meet tough standards on emissions. It laid out three key tests for a UK shale gas industry. These are:

- Strict limits on emissions. This means limiting methane leakage during development, production and well decommissioning, as well as prohibiting production that would entail significant CO2 emissions from changes in land use. The CCC said current regulations fall short of these requirements.

- Gas consumption in line with carbon budgets. This means cutting gas consumption at least in half by 2050 and using shale gas to replace, rather than add to, current gas imports. If carbon capture and storage (CCS) is not available, UK gas consumption needs to drop to around 80% below today’s levels by 2050. A separate report, released last year by the industry-funded Task Force on Shale Gas, concluded that CCS will be “essential” if fracking develops at scale.

- Shale industry emissions offset by more cuts elsewhere. This means the unavoidable emissions from a UK shale gas industry would have to be matched by cuts in other areas of the economy. Offsetting these emissions through other sectors would be possible, but potentially difficult, the CCC said.

The CCC reiterated this advice in its latest annual progress report, published in June. It also said the government should implement new policies to more tightly regulate and monitor shale gas wells, in order to ensure rapid action to address methane leaks.

Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency said in 2011 that the significant global development of shale gas could put the world on a trajectory towards a long-term temperature rise of over 3.5C, far above the Paris agreement limit of “well below 2C.”

Could Shale Gas be Low Carbon?

Some shale gas proponents have argued it could be used to produce low-carbon hydrogen via a steam reformation process, combined with CCS. The hydrogen would replace methane in the gas grid and be used for heating or fuel cells.

Depending on how tightly emissions are controlled during shale gas production, however, this might only cut emissions by 59 percent compared to fossil gas. The figure also depends on what share of CO2 is captured, with 100 percent technically possible, but likely to be more costly.

The CCC said that CCS must be under active development in the UK before a decision to proceed with hydrogen is made. The House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee last year warned gas without CCS could put climate targets at risk.

In 2015, the government abruptly cancelled a £1bn competition to build plants demonstrating CCS at commercial scale. Last year, then-energy minister Andrea Leadsom called a CCS strategy “unnecessary.”

It remains to be seen whether a CCS strategy is laid out in the government’s long-delayed clean growth plan, now expected in September. The Conservative party’s 2017 manifesto made no mention of CCS.

What Does the Government Say on Shale?

The Conservative’s 2017 election manifesto set out ambitious plans to develop the shale gas industry, in a lengthy section that spoke glowingly of its prospects.

This said that shale gas could help reduce carbon emissions “because [it] is cleaner than coal” (see above for more on UK shale gas and coal). The manifesto also said it “could play a crucial role in rebalancing our economy.”

The weakened Conservative administration has abandoned a string of manifesto policies since losing its majority at the general election. Last month, energy minister Richard Harrington reiterated the government’s stance on shale gas, but did not mention emissions, saying:

“Shale gas could have great potential to be a domestic energy resource that makes us less reliant on imports and opens up a wealth of job opportunities. The economic impact of shale, both locally and nationally, will depend on whether shale development is technically and commercially viable and on the level of production. To determine the potential of the industry and how development will proceed, we need exploration to go ahead.”

The government says shale gas operations will only take place in a manner which is safe for the environment and local communities.

The government’s continued support for fracking comes despite low and falling public support. The latest BEIS public attitude tracker, published last month, showed support for fracking falling to 16 percent, its lowest level since the surveys began five years ago.

Opposition now sits at 33 percent, with 48 percent of people saying they neither support nor oppose fracking.

https://twitter.com/DrSimEvans/statuses/893048369035304961 sedimentary basins has not been fully appreciated or articulated. As a result, the opportunity has been overhyped and reserve estimates remain unknown.”

Even while pushing for shale development, government ministers have cautioned that its economic impact will depend on whether it is technically and commercially viable.

Fracking firms themselves are also cautious about promising too much. Cuadrilla’s chief executive Francis Egan said in January he hoped it would become clear within a year whether it was economically viable to extract shale gas from the Preston New Road site.

Jocelyn Timperley holds an undergraduate masters in environmental chemistry from the University of Edinburgh and a science journalism MA from City University London. She previously worked at BusinessGreen covering low carbon policy and the green economy. Reposted with permission from our media associate Carbon Brief.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe