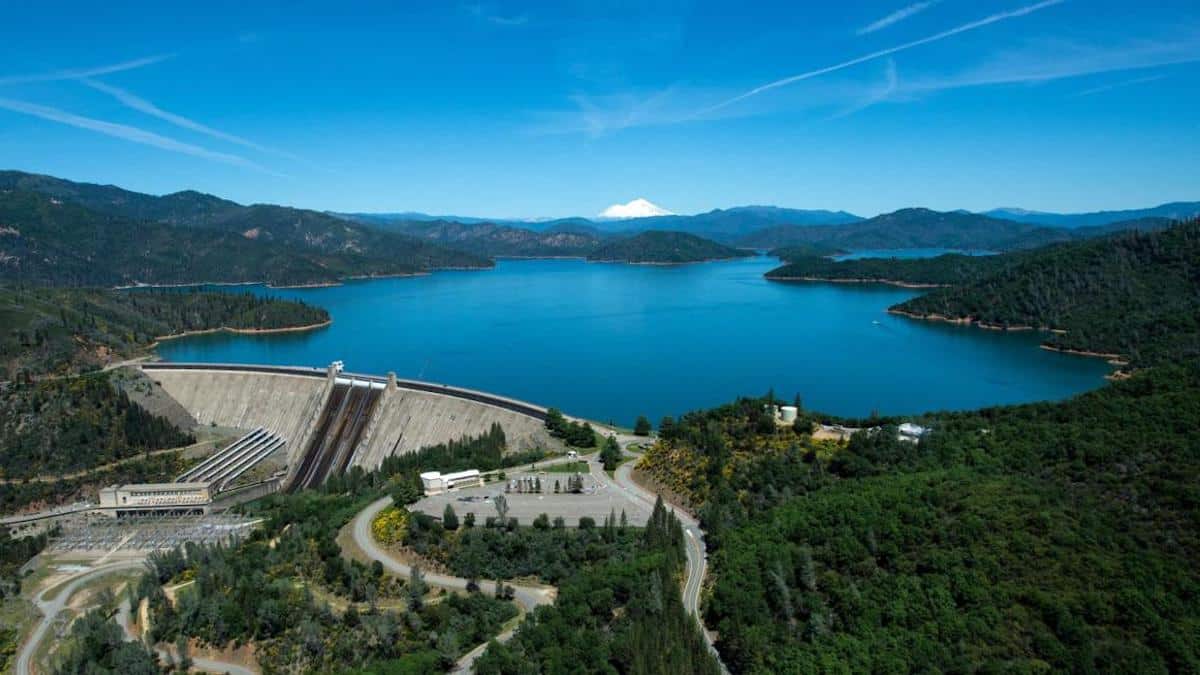

Shasta dam and lake near Redding, California. Kelly M. Grow / California Department of Water Resources

By Tara Lohan

In the aftermath of the Nov. 3 election, President Donald Trump has tried every trick in the book to avoid facing the reality of his loss. A barrage of lawsuits accompanied by disinformation campaigns has attempted to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the election.

But a close look at regulatory actions and executive moves shows that, even as Trump makes a show of refusing to concede or transition power to the incoming Biden administration, his team is pushing through a slew of last-minute rules and regulations.

Many of these changes will harm the environment and public health.

It isn’t surprising that an administration that has attempted to roll back more than 100 environmental protections in the past four years would step up its assault in its waning months. But that doesn’t make the continued attacks any less important. Here’s some of what’s at risk:

1. Tribal Lands

Tribes and environmental groups have fought for decades against a proposed copper mine in an area of Arizona known as Oak Flat, which is a sacred site for a dozen tribes, including the San Carlos Apache.

Now the Trump administration is pushing to fast-track a deal that would transfer ownership of the land, which is in the Tonto National Forest, to Resolution Copper, a firm owned by mining companies Rio Tinto and Billiton BHP.

“Last month tribes discovered that the date for the completion of a crucial environmental review process has suddenly been moved forward by a full year, to December 2020, even as the tribes are struggling with a COVID outbreak that has stifled their ability to respond,” an investigation by The Guardian found. “If the environmental review is completed before Trump leaves office, the tribes may be unable to stop the mine.”

2. FERC Shakeup

Just days after the election, Trump switched up the leadership of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which has a hand in regulating hydroelectric projects, as well as interstate transmission of electricity, oil and natural gas.

Chairman Neil Chatterjee was replaced by fellow Republican James Danly, who has a more conservative view on federal energy policy. Chatterjee, once known as a “coal guy,” had recently advocated for policies supporting distributed energy and for regional grid operators to embrace carbon pricing as a market-based solution for addressing climate change.

3. Hamstringing LWCF

The Great American Outdoors Act, a major conservation bill signed into law in August, allocated .5 billion to help fix national park infrastructure and permanently fund the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

But despite (falsely) hailing himself as a conservation hero at the law’s signing, Trump has already begun undermining the legislation’s effectiveness. An order signed by Interior Secretary David Bernhardt on Nov. 9 allows state and local governments to veto any land or water acquisitions made through the fund.

Chris D’Angelo at HuffPost called the move a “parting gift to the anti-federal land movement.” Montana Sen. Jon Tester, who advocated for the Land and Water Conservation Fund, wrote a letter to Bernhardt urging him to rescind the order. “This undercuts what a landowner can do with their own private property, and creates unnecessary, additional levels of bureaucracy that will hamstring future land acquisition through the Land and Water Conservation Fund,” he wrote.

Senator Jon Tester at a press conference to discuss the Land and Water Conservation Fund in 2018. Public domain

In another blow, officials and conservation groups in New Mexico were surprised to learn that none of their projects proposed to receive funding through the Land and Water Conservation Fund were selected by the Department of the Interior. Some believe the move is political retribution for being critical of the Trump administration and its policies.

4. Dam Raising

On Nov. 20 the Trump administration finalized a plan to raise the height of Northern California’s 600-foot Shasta Dam by 18.5 feet, which would allow for more water storage. The reservoir feeds the federally run Central Valley Project, which funnels water hundreds of miles south to cities and farms. That includes the politically connected Westlands Water District in the San Joaquin Valley, which formerly employed Interior Secretary David Bernhardt as a lawyer and lobbyist.

The state of California has strongly opposed the effort to raise the dam’s height because it would flood the McCloud River, protected as wild and scenic. Conservation groups also say the plan would threaten endangered species such as Chinook salmon, delta smelt and Shasta salamanders.

California Rep. Jared Huffman called it the “QAnon of water projects, meaning it’s laughably infeasible and just not real.”

The staunchest opposition has come from the Winnemem Wintu Tribe, which lost 90% of its sacred sites with the construction of the dam and faces the loss of its remaining sites and burial grounds if the reservoir is expanded.

5. Pesticide Changes

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced on Nov. 20 it was taking away a tool states can use to control how pesticides are deployed. The action could further endanger farmworkers and wildlife.

A Section 24 provision of the Federal, Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act lets states set stricter restrictions on federally regulated pesticides in response to local needs and conditions. But after numerous states sought to limit the use of the weed killer dicamba, the agency will now no longer allow states to set more protective rules for any pesticides.

6. Migratory Birds

A gutting of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 took a big step forward at the end of November, clearing the way for the administration to finalize the rule change by the end of Trump’s term.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service released its Final Environmental Impact Statement to redefine the scope of the law to no longer penalize the energy industry or developers for “incidentally” killing migratory birds.

Pied-billed grebe on an oil-covered evaporation pond at a commercial oilfield wastewater disposal facility. Pedro Ramirez Jr. / USFWS

The agency’s own analysis found that the rule change would “likely result in increased bird mortality” because — without penalties — companies wouldn’t take additional precautions to help make sure birds aren’t killed by their operations.

That’s already proving true. “Since the administration began pursuing its looser interpretation of the law in April 2018, hundreds of birds have perished without penalty, according to documents compiled by conservation groups this year,” The Washington Post reported.

7. ANWR Auction

The Bureau of Land Management announced on Dec. 3 that oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge would go on sale on Jan. 6, following a shortened time frame for the nomination and evaluation of potential tracts to be drilled.

“Once the sale is held, the bureau has to review and approve the leases, a process that typically takes months,” The New York Times reported. “But holding the sale on Jan. 6 potentially gives the bureau opportunity to finalize the leases before Inauguration Day. That would make it more difficult for the Biden administration to undo them.”

Despite the fact that the Trump administration is intent on opening the door to drilling in the 1.6 million-acre coastal plain — one of the wildest places left in the United States — it’s still unclear how interested the oil industry will be. Or how readily they’ll be able to finance their operations. All the major U.S. banks have said they’ll no longer fund new oil and gas exploration in the Arctic.

8. Dirty Air

One week into December, the administration finalized its decision declining to enact stricter standards for regulating industrial soot emissions.

This came despite the fact that the administration’s own scientists found that maintaining the current limits on tiny particles, known as PM 2.5, results in tens of thousands of early deaths each year. And despite the fact Harvard researchers found that those who have lived for decades with high levels of PM 2.5 pollution are at a greater risk of dying from COVID-19.

9. Border Wall

The incoming Biden administration has vowed to not build another foot of the border wall, but the borderlands ecosystem remains under threat as the Trump administration is continuing to push ahead.

In some cases wall builders are even attempting to speed up the work.

“That’s happening from the Rio Grande Valley of Texas to Arizona’s stunning Coronado National Memorial and Guadalupe Canyon, a wildlife corridor for Mexican gray wolves and endangered jaguars,” NPR reported. “At million a mile, the Arizona sections are the most expensive projects of the entire border wall.”

In Arizona they’re needlessly razing vegetation and blasting mountains for roads in remote areas to help enable construction that likely won’t even take place.

10. Harming Whales and Dolphins

Trump may be leaving office, but marine mammals won’t be able to rest easy. NOAA Fisheries issued a rule on Dec. 9 allowing the oil and gas industry to harm Atlantic spotted dolphins, pygmy whales, dwarf sperm whales, Bryde’s whales and other marine mammals in the Gulf of Mexico while using seismic and acoustic mapping, including air guns, to gather data on resources on or below the ocean floor.

In an effort to further efforts for oil and gas drilling, nearly 200,000 beaked whales and more than 600,000 bottlenose dolphins could be “disturbed.” And “pygmy and dwarf sperm whales are expected to be harassed to the point of potential injury, with a mean of 308 whales potentially harmed per year, according to the final rule,” E&E News reported.

Dolphins in the Gulf of Mexico. Carey Akin / CC BY-SA 2.0

11. More Lease Sales

The Arctic isn’t the only place where the rush is on to exploit public lands. On Dec. 9 the Bureau of Land Management updated an environmental assessment for a 2013 plan for leases to extract climate- and water-polluting tar sands on 2,100 acres in northeastern Utah. But then just days late it hit the pause button on the effort.

While that one may be on hold, the administration did kick off the sale of leases for oil drilling on 4,100 acres of federal land in California’s Kern County on Dec. 10. The first such sale in the state in eight years could be canceled by the Biden administration and if not, would face legal challenges from environmental groups.

12. Cost-Benefit Rule

One of the administration’s biggest parting gifts to industry — the “cost-benefit” rule — was finalized on Dec. 9. It would require the EPA to weigh the economic costs of air pollution regulations but not many of the health benefits that would arise from better protections.

“In other words, if reducing emissions from power plants also saves tens of thousands of lives each year by cutting soot, those ‘co-benefits’ should be not be counted,” in the EPA’s new analysis, The Washington Post explained.

The rule would be a big blow to efforts to improve public health and curb pollution.

“The only purpose in making this a regulation seems to be to provide a basis for future lawsuits to slow down or prevent future administrations from regulating,” Roy Gamse, an economist and former EPA deputy assistant administrator for planning and evaluation, told Reuters.

Slowing down the Biden administration will continue to be a big part of Trump’s last month in office — along with the finalization of more rule changes to add insult to injury.

Legal experts have begun mapping which rollbacks will be quick and easy to undo and those that will take sustained effort. But one thing is certain: There’s a long road ahead to reverse dangerous regulations, restore scientific integrity and make up for lost ground on climate change, extinction and other cascading crises.

Reposted with permission from The Revelator.

- Biden Can Leverage Larger Trends to Make Climate Progress ...

- Biden-Harris Climate Plan: 'Not Trump' Is Not Enough - EcoWatch

- 7 Environmental Takeaways From the 2020 Election Season ...

- Trump Named 'Worst President for Our Environment in History' by ...

- Report Urges Biden to Reverse Trump's Environmental Rollbacks - EcoWatch

- How Trump Has Attacked the Environment During the Holidays

- Trump’s Failed Environmental Policies Caused 22,000 Deaths, New Report Finds - EcoWatch

- Wastewater Pollution: EPA Moves to Undo Trump's Weakening of Coal Plant Requirements

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe