Discover How Trees Secretly Talk to Each Other Using the “Wood Wide Web”

As a result of a growing body of evidence, many biologists have started using the term "wood wide web" to describe the communications services that fungi provide to plants and other organisms. David Clapp / Getty Images

By Fino Menezes

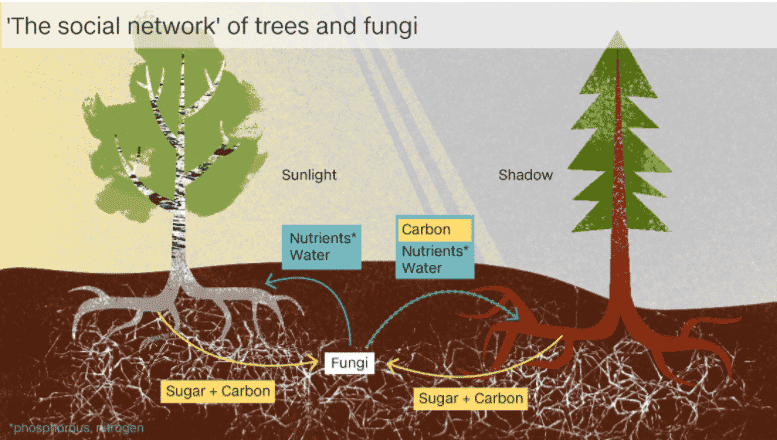

Imagine an information superhighway that speeds up interactions between a large, diverse population of individuals, allowing individuals who may be widely separated to communicate and help each other out. When you walk in the woods, this is all happening beneath your feet. No, we’re not talking about the internet, we’re talking about fungi. As a result of a growing body of evidence, many biologists have started using the term “wood wide web” to describe the communications services that fungi provide to plants and other organisms.

All trees all over the world form a symbiotic association with below-ground fungi These are fungi that are beneficial to the plants and explore the soil. The fungi send mycelium, a mass of thin threads, through the soil. The mycelium picks up nutrients and water, brings them back to the plant, and exchanges the nutrients and water for a sugar or other substance made by photosynthesis from the plant. AlbertonRecord.co.za

This Win/Win Is a Mutually Beneficial Exchange.

While researching her doctoral thesis some 20+ years ago, ecologist Suzanne Simard discovered that trees communicate their needs and send each other nutrients via a network of latticed fungi buried in the soil – in other words, she found, they “talk” to each other.

Simard showed how trees use a network of soil fungi to communicate their needs and aid neighboring plants.

Since then she has pioneered further research into how trees converse, including how these fungal filigrees help trees send warning signals about environmental change, search for kin and how they transfer their nutrients to neighboring plants before they die.

All trees all over the world form a symbiotic association with below-ground fungi. These are fungi that are beneficial to the plants and explore the soil. The fungi send mycelium, a mass of thin threads, through the soil. The mycelium picks up nutrients and water, brings them back to the plant, and exchanges the nutrients and water for a sugar or other substance made by photosynthesis from the plant.

It’s this network that connects one tree root system to another tree root system, so that nutrients and water can exchange between them.

The word “mycorrhiza” describes the mutually-beneficial relationships that plants have in which the fungi colonize the roots of plants. The mycorrhizae connect plants that may be widely separated.

Source: AlbertonRecord.co.za

Check Out This Example of Networking Opportunities.

Sixty-seven Douglas fir trees of various ages were found to be intricately connected below ground by ectomychorrhiza from the Rhizopogon genus. Rhizopogon, which means ‘root beard’ in Greek, is commonly found living in a symbiotic relationship with pine and fir trees, and thus is thought to play an important ecological role in coniferous forests. Areas occupied and trees connected by Rhizopogon vesiculosus are shaded blue, or shown with blue lines, while Rhizopogon vinicolor colonies and connections between trees are colored pink, or shown by pink lines. The most highly connected tree was linked to 47 other trees through eight colonies of R. vesiculosus and three of R. vinicolor.

Source: NewZealandGeographic

BBC News Trees talk and share resources right under our feet, using a fungal network nicknamed the Wood Wide Web. Some plants use the system to support their offspring, while others hijack it to sabotage their rivals. YouTube/BBCNews

The Wood Wide Web Is Earth’s Natural Internet.

While mushrooms are the most familiar part of a fungus, most of their bodies are made up of mycelium. These threads act as a kind of underground internet, now referred to as the “wood wide web” linking the roots of different plants and different species.

By linking to the fungal network they can help out their neighbors by sharing nutrients and information or by sabotaging unwelcome plants by spreading toxic chemicals through the network.

Fungal networks also boost their host plants’ immune systems. Simply plugging in to mycelial networks makes plants more resistant to disease.

Trees in forests are not really individuals. Large trees help out small, younger ones using the fungal internet. Without this help, Simard thinks many seedlings wouldn’t survive. She found that seedlings in the shade, which are likely to be short of food, received carbon from other trees.

Learn more about the harmonious yet complicated social lives of trees and prepare to see the natural world with new eyes with Suzanne Simard’s TED Talk, below.

Source: AlbertonRecord.co.za

Reposted with permission from BrightVibes.

- 6 Ways to Deepen Your Spiritual Relationship to Nature - EcoWatch

- Ethiopia to Plant 5 Billion Tree Seedlings in 2020 - EcoWatch

- Mexican Communities Are Trying to Protect an Endangered Fir Forest - EcoWatch

- Measuring Equity Through City Trees

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe