Toxic Stormwater: The Less Obvious, Often Unknown Danger of Flooding

After Hurricane Ida hit New Orleans and its remnants struck New Jersey and New York, rescue efforts took place via boats and kayaks and people were often forced to walk through standing water. Some the standing water continues in flooded basements. It raises questions about the hazardous materials, such as wood planks, nails, random metal objects, as well as the less visible toxins, such as bacteria and fertilizers, which could be in the water.

When it rains, stormwater runs over land and lawn, sidewalks and streets, pavements and parking lots collecting whatever is in its way. The water gathers fertilizers, pesticides, phosphates, gasoline, heavy metals, litter, plastic and more.

In most of New York City, storm runoff, sewage and wastewater from industries flow through the same pipes. (Queens and Staten Island are the exception: they have separate systems for sewage and stormwater.) The water is funneled to the city’s fourteen wastewater treatment plants.

During intensely wet weather, however, the water is not conveyed to the treatment plants, since it would exceed their capacity. Instead, “during such overflow periods, a portion of the sanitary sewage entering, or already in, the combined sewers discharges untreated into the waterway along with stormwater and debris washed from streets,” according to the New York City Environmental Quality Review Technical Manual. Specially, “during storms, if a greater amount of combined flow reaches the regulator, the excess is directed to outfalls into the nearest waterway (e.g., the Hudson River, East River).”

All it takes to exceed the capacity is rains of a tenth of an inch per hour. And according to the National Weather Service, it rained over three inches an hour when Ida measured at its most intense in Central Park.

This untreated overflow is called Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO). It is discharged out of 460 sites located around New York City. The overflow could contain anything from gasoline to pollutants from industrial facilities to untreated sewage.

Untreated sewage, in turn, might lead to bacteria in the water. Among bacteria, total coliform are widespread in nature, found in soil, water and animal and human waste. Fecal coliform, a subset of total coliform, are present in the gut and specifically in the feces of warm-blooded animals.

A species of fecal coliform is Escherichia coli or E. coli, which can be found in livestock such as cattle, chickens, pigs and sheep. While coliform typically does not cause disease, some strands of E.coli are harmful. Undercooked meat and contaminated water can be sources. The water can become contaminated by leaking septic tanks or sewage pipes; by the fecal matter of birds, humans, livestock and pets; or by the aforementioned untreated sewage. Typically, whether the water is safe cannot be determined by look, smell or taste. Instead the water must be tested.

Other common pollutants carried in stormwater include fertilizers, heavy metals, nitrates, PCBs, pesticides, phosphates and plastic particles — whatever chemicals the water flows over. Unlike water that goes down the drain at home, stormwater that goes down a drain on a street corner is untreated. Carrying its accumulated pollutants with it, it dispels them into waterways, creating not only an environmental hazard but also a health risk.

New York City’s water system is 150 years old. It badly needs an update to separate the sewage and stormwater systems. That said, even if the sewage were no longer to flow out the CSOs, the toxicity of the stormwater would remain, as would the risk of flooding.

In Queens, eleven of the thirteen fatalities were a result of flooded basement apartments. The areas that flooded and where eleven people drowned overlapped with a floodmap that the city issued in May 2021. According to The City, “the interactive map [was] released in conjunction with Mayor Bill de Blasio’s stormwater resiliency plan and required by a 2018 City Council law.”

https://twitter.com/Gothamist/statuses/1435740737161908227

Flooding can destroy a home and its electrical systems. It can create problems for the foundation and lead to structural issues. Mold is a big risk resulting from flooding, which can create health problems. Basements were not only more damaged but are also harder to dry out.

The cleanup can also be a challenge. The repairs can lead to exposure to asbestos, lead and other toxins found in homes. Of course, many products used to clean up also contain chemicals. The U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) advises that for floods at the workplace, “cleaning up spills of hazardous materials, and search and rescue, should only be conducted by workers who have the proper training, equipment and experience.” Similar advice is prudent for floods at home to avoid the health risks.

Yet hiring professionals to carry out these cleanups costs money. And many of those living in basement apartments were living in them precisely because they tend to be cheaper in price.

So what to do? Having the floodmaps in place is great but action must also be taken based on them to ensure that those most at risk are protected. It means that developers should not be allowed to build in flood zones. The mayor’s office estimates that there are at least 50,000 basement apartments in NYC with at least 100,000 residents. Basement apartments raise the issue of the need for housing to be more affordable in New York City or for wages to be commensurate with the cost of living in New York City.

Action is key because as the flooding of New Orleans after Katrina and Ida and now Nicholas, of Houston after Harvey and of New York City after Ida has shown, the threat of flooding is becoming less than a once a century risk. In New York City an estimated 2.5 million residents are already living in storm surge inundation zones.

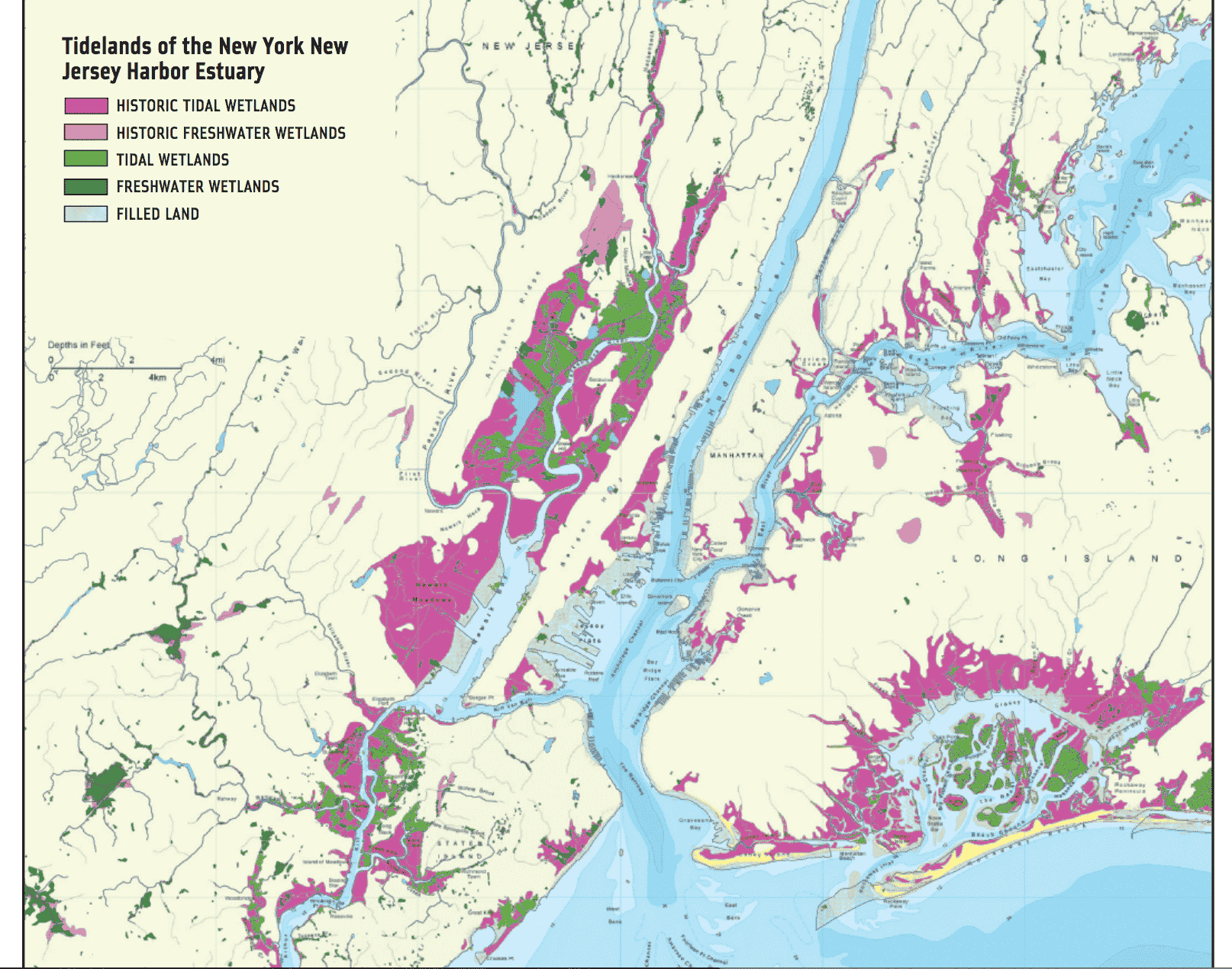

The Netherlands — literally named the nether lands because about one third of the country lies below sea level — and other countries have been at the forefront of adapting to inundation. Coastal zones prone to flooding could be restored as wetlands. New York City currently has only “one percent of its historic freshwater wetlands and ten percent of its historic wetlands, namely in Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island,” according to the Mayor’s Office of Long-Term Planning and Sustainability. It never ceases to amaze how a map of historical wetlands compares with a map of current flood zones.

Tidelands of the New York New Jersey Harbor Estuary. Regional Plan Association

Storm surge inundation zones and depths. NHC, USACE

Existing wetlands could be protected and opportunities for expanding protection and restoration could be pursued. Wetlands help control floods by absorbing floodwater and stabilizing shorelines. Wetlands also help improve water quality by filtering stormwater runoff.

Myriad other strategies exist for reducing flooding and runoff. Rooftop gardens could gather rain and also, unlike tar, cool, and provide food. It might sound like a small thing but if expanded to the scale of the city, it would add up. Playgrounds and below ground parking garages could be constructing to double manner as catchment for water. More green along streets could harvest water. Since 2007, NYC has required permeable pavement for lots with more than 18 spaces of larger than 6000 square feet. Porous pavement is also being implemented. Both could be scaled up. Buzzwords to avoid floods in the new era: permeable and porous. Is it time for the return of cobblestones?

https://twitter.com/CDCEnvironment/statuses/1438156149598064642

Tina Gerhardt is an environmental journalist. She covers international climate negotiations, energy policy, sea level rise and related direct actions. Her work has been published by Grist, The Progressive, The Nation, Sierra and the Washington Monthly.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe